Authored by Nwankwoala HO*,

Abstract

This study is aimed at assessing the influence of community resilience to flood risk and coping strategies in Bayelsa State, Southern Nigeria. 1505 copies of administrative questionnaires were distributed to obtain information concerning the perception of flood vulnerability and resilience in carefully chosen communities applying stratified and random sampling techniques. However, 1265 questionnaires were repossessed for further analysis and the results indicated that incident of flooding in Bayelsa is seemly a recurring problem occurring yearly with loss of numerous lives and properties. The predominant coping strategies are sandbag dykes’ construction, channel/drainage building, opening/maintenance of clogged drains/channels, land reclamation, elevating buildings floor beyond water level, relocation, and elevation of belongings from ground floor. This study also revealed that 43 (11.05%) communities recorded low flood vulnerability levels, about 287 (73.78%) communities had moderate vulnerability features whereas 59 (15.17%) communities indicated high vulnerability to floods in the State. The study concluded that greater portion of Bayelsa State were vulnerable to flooding. Encouragement of periodic flood assessment studies as well as provision of adequate preparedness plan to surmount future occurrence of flood disaster in communities that are highly and moderately vulnerable to floods is recommended. Timely intervention by government agencies to assist flood victims in the State is necessary.

Keywords:Resilience; Flood risk; Vulnerability; Coping strategies; Bayelsa state

Introduction

Flooding is amongst the highly destructive, frequent, and prevalent environmental hazards usually of different kind and magnitude [1]. Flood is a natural event that is unavoidable with frequent occurrence in waterways and natural drainage structures resulting in the destruction of lives, natural resources, and environs together with health challenges and economic loss on yearly basis [2-5].

The emergence of flooding all over Nigeria takes the dimension of coastal, flash, river, and urban flood [6]. Bayelsa State is situated in the core of the Niger Delta and in line with these reasoning, it is adjudged to be among the highly susceptible states to inundation in Nigeria. Annual Flooding resulting from coastline and riverine overflows appears to be afflicting a lot of locales in Bayelsa and the Niger Delta region of Nigeria long before the period of climatic changes cognizance. Recently, disasters due to flooding in Bayelsa State and most sections of Nigeria have led to so many deaths and property loss, in addition to endangered eco-diversity. According to [7,8] , the annual flooding experienced in Bayelsa State triggered by climate change causes loss of lives and fiscal assets as well as decreased attendance in schools with multiplier aftereffects on the educational system.

The floods in the year 2012 and the later one in 2018 encountered in the Niger Delta Region; inspired by global climate change had severe aftermath specifically on the area of education in Bayelsa State which led to the closure of schools for an interval of one month. The floods of 2012 are portrayed to be a flood disaster with the greatest degree of violence and destruction in the annals of Nigeria which leads to the displacement of 2.3 million humans, the killing of over 363 persons and damaging of approximately 597,476 buildings [9]. The 2012 historical floods as advanced by Akpokodje EG [10] was triggered by many factors like: Abnormal rains linked with excessive climate conditions triggered by climatic changes and global warming, inappropriate land use and development along natural water channels, clogging of drainages and street channels and the discharge of excess water from Shiroro, Jebba and Kainji Dams on the Niger river and Ladgo Dam in Cameroun.

Nevertheless, the famous 2012 floods in Nigeria are perceived to have its origin from the inundation of Rivers Benue, Niger, and their tributaries. These tributaries spring partially from selected runoffs generated at the far end of the foothills of Futa Jalon Mountains situated within the Republic of Guinea; and finally settles in the delta plains of the Deltaic region. The Niger-Benue River scheme also releases its contents through the main coastline floodplains of the Deltaic region into the Atlantic Ocean.

In accordance with Fubara D [11], adverse impacts of the 2012 historic floods are more severe than the pollution of the Niger Delta in the past six decades by the action of oil companies. The reasoning is based on the fact that the whole effluent discharged, the acidified waters, the waste pits etc. are all eroded into the various water bodies. Since many tributaries of the Niger-Benue River scheme uses Bayelsa State as the pathway for discharging their water into the Atlantic; the state displayed extremely elevated vulnerability index to flood hazards originating from these river scheme and from sea level rise motivated by climatic changes [12]. In relation to sustainability, vulnerability can be referred to the degree of or the motive behind a community’s susceptibility to disruption that might compromise the continuous existence of the community. In such manner, vulnerability is linked to resiliency- the extent to which a community could withstand and likely bounce back from a disruption, like floods [13].

However, USAID [14] defined resilience as ‘’ the ability of a populace, household, community, country, or a system to assimilate, adjust to bounce back as well from distress in a way that reduces prolonged vulnerability, equally enable widespread growth.’’ These could be attained through the implementation of adaption and mitigation strategies planned to assist the victims achieve sustainability to hazards [15,16] in a recently reviewed literature on resilience, described Community resilience as the ability or the process of a community to acclimatize and operate at the instance of disturbance. Ostadtaghizadeh A, et al. [17] described Community resilience as the capability of systems, societies, or communities vulnerable to risks to withstand, incorporate, adjust, and bounce back from the impacts of such risk at the appropriate time and efficiently through the protection cum reestablishment of its vital structures and functions. Therefore, Community resilience is seen as an amorphous notion that was implied and used diversely by diverse groups.

This study, therefore, is aimed at identifying anthropogenic activities that may lead to Community vulnerability to floods in the State; assess factors that influence community resilience to floods in Bayelsa State, Nigeria as well examine the extent at which community resilience can be achieved through the integration of traditional (structural) as well as conventional (Non-structural) methods.

The study shall assist in building Community Resilience Framework in Bayelsa State that will assist in reducing flood vulnerability aimed at making communities safer and more resilient to disasters. More importantly, this study helps in ascertaining the influence of flood resilience measures on sustainability of future generations as well as determine the effect of flood on social, economic and ecosystem variables as well as the manner in which communities’ were coping with the flood.

Description of the Study Area

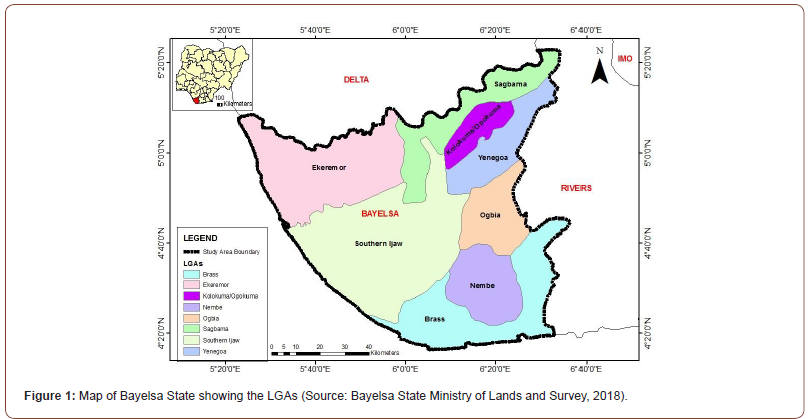

The study area was the entire Bayelsa State, Nigeria, located in the Central Niger Delta and situated between the Niger and the lower Niger floodplain of the Niger Delta Region. It falls within the geographical location of latitude 4o 20’N and 5o 20’N and longitudes 5o 20’E and 6o 40’E (Figure 1). The state shares boundary with Delta on the North, Rivers on the East and is bounded on the West and South by the Atlantic Ocean. . It has a population of about 1.7 million people based on the Nigerian 2006 census [18].

The study area has a tropical climate with two distinct seasons, wet (April-October) and dry (November-March). It also experiences two distinctive prevailing winds. These are the dry and dusty laden tropical continental air mass and the moist tropical maritime air mass. The tropical continental air mass is otherwise known as Harmattan wind [19]. It is a dry cold wind, embedded in the North-East trade wind that blows over the area from December to February (dry season). Alagoa EJ [20] posited that the mean annual rainfall ranges from 2,000 to 4,000mm and spreads over 8 to 10months of the year between the months of March and November, this coincides with the wet season. Bayelsa State is located within the lower delta plain believed to have been formed during the Holocene of the Quaternary period by the accumulation of sedimentary deposits. The major soil types in the state are young, shallow, poorly drained soils and acid sulphate soils. Youdeowei PO and Nwankwoala HO [21] posited that the major soil types of the study area are light to dark grey; fine sand to silty clay. Like any other area in the Niger Delta, the vegetation in Bayelsa State is composed of mangrove forests, freshwater swamp, and lowland rain forest. Commercial timber species are also found in the area [22-24]]. The main occupations include farming and fishing.

This study employed the use of Landuse map of Bayelsa State acquired from the Landsat Imagery of 30m x 30m and the drainage network, road network, and communities location extracted from the topographic map of 1: 100,000 scale of the study area; and soil map derived from the FAO website. The secondary data included the population data of 2006 of the communities from Bayelsa State obtained from National Population Commission [18]. Topographic map was obtained from Surveyor General’s office, Ministry of Lands and Survey, Bayelsa State.

Methods of Study

Sampling techniques and sampling frame

The stratified with random sampling techniques were employed to carefully choose the sample size from the entire population of area under study. The study used household population of chosen communities. In the chosen communities, the various houses were labeled with even and odd numbers.

The houses labeled with odd numbers were chosen and questionnaires were administered on the heads of selected households. In households were the head is not available, the opportunity of completing the questionnaire was given to next individual in the hierarchy. However, stratified with random sampling remain the techniques employed to choose communities from each Local Government Areas (LGAs) in the State. All the communities in the State were stratified into two groups according to their LGAs; namely communities that often experience flooding and the ones that hardly witness flooding. From the group that often experience flooding, not less than 5 communities were chosen randomly from each LGA, given a total of 41 chosen communities to carry out the survey (Table 1).

Table 1:Study Population and Sample Size.

Also, stratified sampling technique was again adopted to choose the sampled houses in each community. This was achieved by initially listing and numbering the houses and thereafter the houses labeled in odd numbers were taken and regarded as the sampled houses. The number of households in every sampled house was then counted and random sampling was utilized to choose the total sampled population used for questionnaire administration (Table 2). The entire state questionnaire administration follows a random sampling technique that selected 1505 respondents, whereas a total of 1265 (84.1%) copies of finished questionnaires were recovered for furtherance of the analysis.

Table 2:Administration and Retrieved Analysis of Questionnaires.

Validity and reliability of instrument

Research instruments are usually faced with the burden of validity and reliability. Research instruments are the means or tools employed for collecting data which includes; questionnaires, interviews as well as published materials. These, however, can be confronted with the problems of validity and/or reliability as earlier observed. The research was subjected to content validity; however, the research instrument (questionnaires) was subjected for validation of its content. Reliability is the consistency in achieving similar results when the same method is applied to other similar situations. It, therefore, involves reproducible techniques and their dependability all the time. The reliability of the study was determined by adopting the Test-Retest method whereby reliability of instrument was made to undergo a pre-test analysis that utilized 10% from the totality of questionnaires to be distributed (that is 150 copies from the total of 1505 copies). That is, 10% of the copies of the instrument was directed to a smaller proportion of respondents and the findings was subjected to the Cronbach alpha test to acquire a reliability test score (measured between 0 and 1, with values tending towards 1 as being reliable) for a content validity of the instrument to be utilized. The outcome for this study was 0.72 (72%) content validity.

Results and Discussion

Factors influencing the extent of community resilience to flooding in Bayelsa State

Table 3 unveils the analytical results of factors affecting the extent of community resilience to flooding in the State. It indicated that 78.2% of responses accepted existence of social networks like electricity, water, and telephone as a vital factor in building resilience of communities, 82.7% admitted that support of relatives, neighbors as well as friends contributed to community resilience, whereas 76.6% of the responses indicate housing units, shelters, business/industries, and critical infrastructures’ geographical location influences resilience of communities.

Table 3:Factors influencing the extent of community resilience to flooding in Bayelsa State.

Note: Percentage in brackets

Also, over 70% of responses agreed that physical infrastructure, transport facilities and communication accessibility are factors essential for building community resilience. However, other factors like awareness/information acquired from prior experiences with floods shared with relatives, neighbors, and friends, Livelihoods pattern, education level and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) availability could possibly influence the resilience of communities to flood hazards in the State.

Community flood resilience measures

Community resilience measures involves the engagement and participation at community and householder level. Specific actions are needed to possibly carry out resistance and resilience building measures. And ownership of such responsibility will certainly become a key element of effective resilience raising, which usually lies on the house holder and/or community group. Resilience measures which include adaptation, reduction and mitigation plans which could be linked with flood risk management measures are classified as traditional (structural) and conventional (Nonstructural) measures.

Traditional (Structural) measures

These are important with physical protection from hazards. It involves building of physical structures to avoid flooding of the entire house or a portion of it. Structural measures place emphasis specifically on utilizing local technology and expertise. In these measures, no real planning goes into their implementation. The structural measures involve the basic principles of storing, diverting and confinement of floods.

It consists of building infrastructure such as levees and dams or river dike that altars the river flow. Appropriate traditional measures of flood resilience embraced in localities include:

1. Construction of sandbag/earth dikes

2. Coastal embankment to protect roads

3. Opening and protection of blocked drainage systems and channels

4. Channelization/drainage building

5. Land reclamation and structural stabilization

6. Afforestation

7. Elevation of buildings floor beyond the level of water

8. Lay floor guards on Door steeps

9. Construct trenches in gardens to redirect floodwater

10. Evacuation of belongings from Ground floor

11. Relocation (IDP camps, safer grounds, neighbors/friends’ houses, relative places, etc.)

Conventional (non-structural) measures

The Non-structural measures can be perceived as a collection of mitigation and/or adaptation measures that do not apply traditional (structural) flood defenses. They include various mitigation measures which in no way alter the river inflow and these may include the responses of individual’s behavior to the threat of flood. And these measures reduce damage without influencing the current of the flood incident. The non-structural measures aim to preserve individuals and their property away from floods. These measures comprise all flood management measures not at all dependent on large scale defenses:

1. Programmes that raise awareness and orientation in communities (e.g., forecasting cum flood warning signals)

2. Local preparedness plan development

3. Establishment of Community Flood Management committees for implementation of local strategies

4. Provision of a flood forecast-warning signal that is efficient

5. Floodplain regulations ( that includes land use planning strategies)

6. Flood risk assessment systems

7. Economic instruments (including flood insurance)

8. Maintaining community drainage systems in existence as well as building extra small, scaled ones

9. Building codes and zoning

10. Flood proofing

11. Health and social measures, etc. These measures appear today as indispensable compliments of structural engineering solutions.

In actual fact, our country Nigeria especially the Niger Delta Region focus on challenges of floods which threatens socio-economic and environmental systems globally, however government have to work towards increasing resilience and also lower vulnerability to flood impacts.

Integration of traditional (structural) and conventional (non-structural) methods

Table 4:Integration of traditional (structural) and conventional (non-structural) methods.

Note: Percentage in brackets

The analysis of Bayelsa traditional and conventional methods implemented to manage flood are shown in Table 4. Above 70% of the responses confirmed that the various traditional methods applied includes sandbag dykes construction, clogged drains and channels opening/maintenance, channel/drainage building, land reclamation, elevation of buildings floor beyond the level of water, resettlement as well as elevation of belongings from ground floor. Similarly, above 70% of responses also admitted that orientation along with awareness raising programmes (like flood warning signals), as well as development of local preparedness scheme were the structural methods embraced by the communities.

Table 5 displayed the degree of resilience both methods achieved. From the results 22.7% agreed the degree was high whereas 64% affirmed it to be low. Table 6 showed the influence of flood resilience measures on sustainability of future generations. The analysis indicated that above 70% of the responses admitted that accessibility of flood management committees, programmes that raise community awareness/orientation, hazard/vulnerability assessment reports, as well as local preparedness plan development are likely resilience measures which can influence sustainability of generations to come.

Table 5:Degree of resilience achieved by these traditional /conventional methods.

Effect of floods on social, economic, and ecosystem variables

Table 6:Influence of flood resilience measures on sustainability of future generations.

Table 7:Effects of Floods on Social Activities.

Note: Percentage in brackets

Table 8:Flood effects on Economy.

Note: Percentage in brackets

Table 9:Flood effects on ecosystem.

Note: Percentage in brackets

The effect of floods on social, economic and ecosystem variables are displayed in Tables 7, 8 and 9, respectively. The outcome unveiled that 59.2% agreed that social life of residents was impacted by flood while 55.6% agreed they experienced damage to health facilities resulting to health effects during the floods.

Concerning the health issues, above 70% of respondents believed that flood resulted in getting people sick of malaria fever, cough with skin diseases like measles and 88.7% complained that flood affected communities were isolated from public amenities like health centres, youth clubs, and community playgrounds. More so above 70% of respondents agreed that schools were locked down for three weeks and four weeks owing to floods (Figure 2a & 2b).

The flood impact on economy presented in Table 8 reveals that 32.1% of the responses confirmed that their houses were damaged during the flood while 39.2% admitted that their houses were slightly damaged. Relating to issues on damaging of belongings, 31.3% claimed that their belongings were damaged totally, 40% said slightly damaged while 27.8% said no damage of belongings was experienced. Among the lost belongings itemized in the study area, the respondents disclosed that more than 40% agreed that they lost furniture and other items of great value. Furthermore, 65.3% agreed that lives were lost during the flood and over 60% attested that floods resulted to loss of daily wage, disruption of water and electricity, and disruption of transport and communication modes.

Table 9 presents flood effects on ecosystem activities. It disclosed that over 50% of respondents reacted that flooding lead to loss of livestock and habitat, households experienced farms and crop damage during floods, dispersal of weed species and invasive species, silting of ponds and lakes, including riverbank and soil erosion.

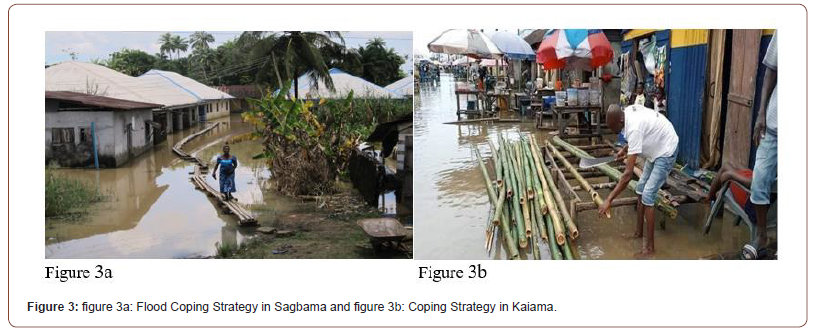

Residents coping strategy to floods

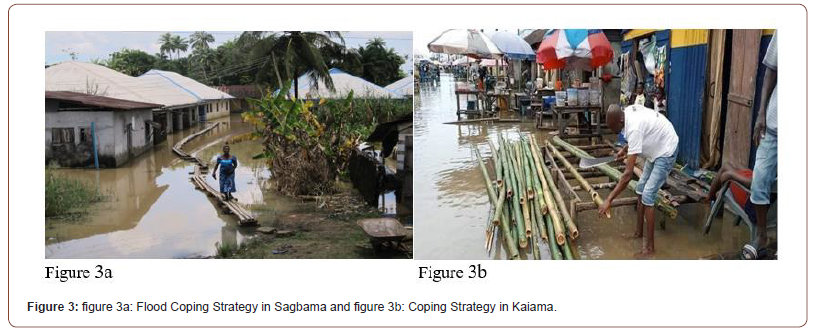

Table 10 indicates some of the coping strategies adopted when flooding occurs in Bayelsa State. Consequently, above 60% of the responses consented that canals building, evacuation to higher/ safer places, construct trenches in gardens/farms to redirect flood water, together with evacuation of properties from house were the leading strategies adopted to cope with the occurrence of floods in the State (Figure 3a & 3b).

Table 10:Flood Coping Strategies in Bayelsa.

Identification of anthropogenic activities that may possibly enhance community vulnerability to flood in Bayelsa State

Table 11 depicts the anthropogenic activities that may possibly enhance community vulnerability to flood in the State. The table disclosed that 66.4% of the respondents admitted increased urbanization with development of urban structures in the vicinity of river channels as an anthropogenic activity, 80.3% admitted water channels poor drainage capacity arising from facility blockage by waste and debris, 73.4% admitted developments along drainage facilities/flood drains whereas 81% admitted carrying out fast paced deforestation. Also 68.3% admitted that dumping waste and debris indiscriminately along natural drainage channels amplifies vulnerability to floods.

Table 11:Anthropogenic activities.

Note: Percentage in brackets

Relief assistance

Table 12 portrays the analysis of relief assistance donated to flood victims and their evacuation styles. The results disclosed that 72.2% of the responses claimed not receiving any assistance from government or other institutions in the course of floods or thereafter whereas 27.8% confirmed receiving assistance.

Table 12:Relief Assistance and Evacuation Styles During Flood.

Taking into consideration the type of assistance given to the victims of the flood hazard, a greater part of the respondents (47.5%} accepted that they were provided with food items most of the time, whereas 13.4% and 13% confirm receiving financial grants and children school materials respectively. Regarding government’s timely response and value of items provided throughout and after the floods, 46% of respondents admitted that it is always belated whereas 25.2% confirmed that it is inadequate most of the time. Also 57.4% of the responses confirmed that they were able to evacuate their households on the occasion of floods; and 37.4% attested to the fact that flood victims were evacuated to public school buildings, 20% admitted being evacuated to IDP Camps whereas 3.5% admitted that they migrated to other less vulnerable areas.

Conclusion

The study findings disclosed that 2020.40 km2 (12.9%) of Bayelsa State exhibited low vulnerability to floods. Moderate vulnerability and high vulnerability areas spread over a spatial extent of 9342.04 km2 (59.8%) and 4248.95 km2 (27.3%) respectively. Thus, a greater part of Bayelsa State covering 87.1% of the area recorded moderate with high vulnerability echelons, also perceived as areas prone to floods using the factors under consideration. Furthermore, approximately 43 (11.05%) communities consisting of Akassa, Agberi, Agbalamabugokiri, Bolougbene, Bwama, Egwema, Odioma, Sangana, Tomkiri, Twon, Zarama are among those that fall within low flood vulnerability echelons. The communities with moderate vulnerability feature were about 287 (73.78%) comprising Abagbene, Adagbabiri, Amassoma, Brass-town, Botokiri, Ekeremor, Fangbe, Kaiama, Korama, Nembe, Ogboinbiri, Opolo, Sagbama, Tombia as well as Uruama. However, 59 (15.17%) communities in the State show high vulnerability to flood. Some of the communities are Abolikiri, Agbura, Amakalakala, Biogbolo, Ekeki, Fantua, Imiringi, Okpokiri, Okpoma, Otueke, Oweikorogha, Peremabiri, Polaku, Swali and Yenagoa.

This research unveiled that 27.8% of the respondents fall within the ages of 20 - 30 years, 23.5 % are 31 - 40 years, 26.1% are 41 - 50 years while 17.4% are 51 - 60 years. Analysis of responses to marital status shows single (22.6%), married (63%), divorced (0.9%), separated (3.5%) while widowed (5.2%) and common relationship (3.5%). The results also showed that 0.9% had primary education, 13.9% had secondary education, 33% had lower tertiary education and 50.4% had university education whereas 1.7% did not have formal education. Above 80.0% of the responses on household size fall within the range of 1 - 10. The responses on religion settings in the State indicated that 95.7% were Christians, whereas 4.3% were into Islamic religion practice. Also 59.1% of responses confirmed that the location of communities under study were in areas prone to floods or near a river. Going further, 33% of responses confirm staying in coastal areas whereas 7.8% affirmed that they are resident in urban areas with huge artificial impervious surfaces. Consequently, 92.2% of the responses indicated having bitter experience concerning environmental hazards in the preceding five years and flooding was perceived to be among the major hazards.

The 2018 flood was perceived to be high in height as over 80% of responses in different occasions consented that the flood height was over feet, equivalent to ankle, knee and over knee. Moreover, 40.9% of respondents admitted their reason for continuous stay in flood prone areas is job proximity, 16.5% agreed on close to relatives and 13.9% to sustain and secure home grounds. The analysis further disclosed that 72.2% of the responses claimed that no assistance was gotten from government or related institutions in the course of floods or thereafter whereas only 27.8% affirmed receiving assistance.

Considering the items provided for flood victims, majority (47.5%) admitted that they were provided with food items at all times, 13.4% affirmed financial grant whereas 13% affirmed children school items. On the anthropogenic actions that heighten community vulnerability to flood, 66.4% accepted urbanization increase with an extension of urban structures near river channels whereas 80.3% affirmed water channels poor drainage capacity which arises from facility blockage by waste and debris. Over 70% of responses admitted that accessibility to physical infrastructure (i.e., bridges, roads, levees, dams etc..) together with communication/ transport facilities are indispensable factors for community resilience. Though, notable factors such as knowledge/information acquired from past flood experience shared with friends, neighbors, and relatives, along with livelihood pattern substantially influence the resilience of communities to floods in Bayelsa.

On the issue of resilience actions embraced during flooding, above 70% of responses attested to using various traditional methods like sandbag dykes construction, channel and drainage building, clogged drains/channels opening/maintenance, reclaiming of land, elevation of building floor beyond the level of water, relocation in addition to evacuating belongings from ground floor. Similarly, above 70% of the responses attested to orientation/ awareness raising programmes in communities (inclusive of flood warning signal), as well as establishment of local preparedness plan as the Non-structural measures they adopted. Findings further revealed that 32.1% of the responses admitted that their house was damaged during the flood while 39.2% attested to the fact houses belonging to them were slightly damaged. As regards to the damage on the belongings, 31.3% said that their belongings were damaged totally, 40% said slightly damaged while 27.8% admitted not having any experience on damage of belongings.

The study further established that flood really affected the socio-economic and ecosystem activities of Bayelsa communities, in spite of that the role of government was rarely seen to support the flood victims. Furthermore, flood incident is seemingly a yearly recurring concern with lives and properties lost numerously in the State.

To read more about this article...Open access Journal of Hydrology & Meteorology

Please follow the URL to access more information about this article

To know more about our Journals...Iris Publishers

To know about Open Access Publishers