Introduction

Despite expanded efforts to reduce substance use disorder (SUD) and related harms over the past decade, the prevalence of SUD continue to rise among veterans and the general population [1- 3]. According to a 2015 report, SUD prevalence among the general population is 8.4 percent in the United States [4]. The prevalence of SUD among military veterans is even higher than the general population at approximately 11 percent [1].

It is well known that SUD impedes participation in meaningful occupations, often negatively impacting social relationships in settings such as at work, school, and home [5]. Literature suggests interventions that provide cognitive challenges and aid people’s ability to structure their time, engage with communities, and socially interact can facilitate SUD recovery [6-8]. Building on this literature, an occupational therapist, an art therapist, a professional director, and a professional actor collaboratively developed a sixweek occupational therapy theatre intervention for veterans recovering from SUD. Participants memorized lines and rehearsed the play “Altered”-a modern-day adaptation of Greek myths touching on themes of addiction without overtly discussing it-for three hours, three times a week for six weeks. Following six weeks of rehearsal, the play was performed in a local theatre company on two consecutive nights, free and opens to the public. Performances were followed by a ‘talk-back’ between the audience and participants, allowing the audience to ask questions and providing participants an opportunity to engage with the community and share their experiences.

[9] previously described procedures of this intervention and reported preliminary feasibility and acceptability data. Preliminary quantitative results suggested high attendance, significant improvements in social and occupational participation, and unusually high drug abstinence rates during and following the intervention [7]. As part of this larger, explanatory sequential mixed methods feasibility and acceptability study, this article report’s findings from thematic analysis of qualitative data obtained via focus groups conducted with all participants immediately following the six-week intervention. The primary aim of this qualitative analysis was to identify and more deeply explore potential mechanisms of change contributing to the previously observed positive quantitative outcomes [7].

While quantitative and qualitative findings of this study were reported separately, these data were integrated in several ways, as suggested by mixed-methods experts [10], and were in no way conceptually distinct. The same theoretical framework informed both types of findings; data were concurrently collected, and each type of data analysis was informed by the other. More specifically, following suggestions from methodology experts [11] this study used qualitative data to illuminate how and why changes occurred, providing insight into the mechanisms of change underlying quantitative outcomes.

Background

According to the [5] SUD is characterized by persistent substance use that interferes with a person’s participation in other meaningful occupations, and neurobiological changes associated with tolerance and withdrawal (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Likewise the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases and Health Problems (ICD-10) defines substance dependence (dependence syndrome) as “a cluster of physiological, behavioral, and cognitive phenomena in which the use of a substance or class of substances takes on a much higher priority for a given individual than other behaviors that once had greater value” [12]. Both definitions emphasize that addictive substance use reduces the perceived value of and participation in other, previously meaningful activities. As a result, people with SUD often experience occupational deprivation – a lack of meaningful engagements that can provide or contribute to identity, enjoyment, volition, and structure [13].

Occupational Deprivation

Occupational deprivation describes a situation in which circumstances preclude occupational participation that could otherwise provide meaning, structure, enjoyment, volition, purpose, and identity (among other benefits) [14]. In addition to the above-mentioned diagnostic criteria, many empirical studies have depicted an inverse relationship between problematic substance use and health-promoting occupational participation [15]. For example, [7] found that SUD directly contributed to isolation from others and avoidance of valued activities. Conversely [8] demonstrated that greater occupational participation in early SUD recovery supports drug abstinence efforts, and several animal model studies of addiction over decades have suggested that environmental enrichment in the form of adding opportunities to participate in social interaction and play can be preventative, support abstinence following chemical addiction, and actually reverse the disease processes of addiction [16-18].

Social Participation

One form of occupational engagement–social participation–is particularly relevant to studies of addiction. Research suggests that increased social engagement can facilitate recovery from SUD [7, 19, 20] and that social isolation greatly increases risk of developing an addiction and is associated with poorer recovery outcomes [15, 21] found a 27% decrease in likelihood of relapse among people with alcohol use disorder who enhanced their social networks. Biosvert et al. (2008) similarly found a significant reduction in relapse rates among people in addiction recovery who participated in a peersupport community. As suggested by [18] social participation may help address some of the neuropath logical changes that result from chronic drug use. For instance, activating executive function systems via social interaction may help strengthen cortical networks that can help with behavioral inhibition that have been diminished through chronic drug use.

Cognitive Challenge

Several studies have also suggested that addictive drug use results in neurobiological changes to the reward center and prefrontal cortex [22, 18, 23]. More specifically, mesolimbic dopaminergic reward center pathways are reinforced by recurrent ingestion of many drugs of abuse [23]. Concurrently, seratonergic inhibitory pathways from the prefrontal cortex are often diminished [22]. The functional implications of these neurological changes are that people tend to display greater impulsivity, preference for small, short-term rewards over larger, long-term rewards, and decreased self-efficacy or control over one’s actions, experienced as diminished autonomy and perceived lack of ability to direct one’s own life toward desired consequences [23-25].

Some have suggested that interventions entailing cognitive challenges–particularly working memory training and episodic future thinking can help reverse some of the pathological changes that result from chronic drug use [6, 26]. Activating the prefrontal cortex through memory training and future thinking have been shown to decrease delay discounting, which is the tendency to devalue future rewards and over-value immediate rewards, as is common in addictive disorders [26].

Theatre

The theatre intervention examined in this study is unique in that it was specifically designed to address the factors pertinent to people in early SUD recovery outlined above. From the start of the six-week intervention, participants are engaged in future thinking and memory training; they are constantly preparing for the performance (future thinking) that will take place at the end of the six-weeks, and they are memorizing their lines throughout the intervention. They are also expected to participate in activities that increasingly challenge executive systems. Participants must first read their lines while seated at a table with others; they then are given instructions from the director about where to stand or how to move while reading their lines on stage with others; eventually participants must memorize their lines and deliver them to others while also standing or moving as directed and finally, participants are expected to do all of this in front of a live audience that may laugh, applaud, or provide other external distractions. In addition to the cognitive challenges introduced by this intervention, participants also experience regular social interaction, gain the temporal structure provided by a rigorous rehearsal schedule, must manage their time accordingly, and have the opportunity to explore different identities and social situations in the context of the theatre process.

While theatre has not yet been established as an evidencebased intervention for SUD recovery, historically, many have used this modality to promote wellness in various mental health populations [27]. Hospital occupational therapy departments have implemented theatre and noted positive outcomes in social and occupational participation and reduced symptoms of severe mental illness (SMI) [28] provided preliminary data suggesting theatre interventions contribute to prosaically behavior and decrease antisocial behavior in male adolescent youth. [29] Demonstrated that theatre-based interventions improved social deficits in persons with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Another study showed a 4-week theatre-based intervention increased cognitive and social function in a sample of community-dwelling adults with cognitive decline as well as, on a separate occasion, less educated, lowincome older adults living in subsidized retirement homes [30, 31]. While the occupation-based theatre intervention is unique to this study, VA hospitals have addressed PTSD using drama therapy and found promising preliminary outcomes [32]. Finally, historically, literature suggested theatre for prisoners significantly reduced the rate of re-arrest more than any other motivational program in correctional systems across the United States. More recent use of theatre in correctional facilities such as the well-known Shakespeare Behind Bars program is a more recent testament to the power of this modality.

Method

Design

This qualitative analysis was part of a larger, sequential mixed methods design with concurrent data collection. Following concurrent qualitative and quantitative data collection, quantitative feasibility and acceptability outcomes were analyzed. Findings from this analysis were reported in [9]. Thematic analysis as described by [33] was used to explore themes of participants experiences collected via focus groups. These data were used to better understand mechanisms of change observed in quantitative data.

Participants

Participants included eleven veterans with an active SUD diagnosis who were all in acute outpatient SUD treatment at the time of recruitment. Considering the high rate of co-occurrence between SUD and other psychiatric conditions [34], participants with co morbid mental illness diagnoses were included to enhance the external validity of findings. Participant diagnoses included: polysubstance dependence, cocaine dependence, alcohol dependence, substance use/abuse, alcohol abuse, tobacco use disorder, cannabis abuse, non-dependent upload abuse, hypnotic or anxiolytic abuse, neurotic depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) depression not otherwise specified (NOS), anxiety disorder NOS, dysthymic disorder, narcissistic personality disorder, sexual disorder NOS, bipolar affective disorder NOS, bipolar I disorder mixed, major depressive affective disorder recurrent episode severe without psychosis, impulse control disorder, suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, lack of housing, and inadequate housing.

Procedures

Recruitment

Clinicians informed all veterans enrolled in a SUD recovery program at either of two recruitment sites (a VA Medical Center and a VA residential program, both in a Midwestern city) about the opportunity to participate in this study. Interested veterans were given more information by the principal investigator. The researchers obtained Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 authorization (Pub. L. 104–191; HIPPA), informed consent, and additional audiovisual consent from all participants prior to beginning the six-week theatre intervention. Following the first intervention, a second recruitment phase was conducted, and a second intervention was implemented.

In faze one, 14 participants consented to participate and 7 dropped out prior to the intervention, leaving 7 participants in faze one. In phase two, 7 consented to participate and 3 dropped out, leaving 4 participants in phase two for a total of 11 participants over two phases.

Data Collection

Quantitative data were collected at baseline and within one week of the end of the intervention as well as 6-week and 6-month follow-up points. Additionally, within one week of the end of each intervention phase, veterans participated in a single focus group. The same questions were used during each focus group as a guide, but the conversation naturally varied from group to group based on what participants shared. At the start of each group participants were told that everything they shared would be de-identified, and participants were reminded of the importance of hearing everyone’s opinion but also informed that if they did not feel comfortable sharing on a topic they were welcome to not respond. The principle investigator facilitated the focus groups. Other intervention personnel were not present during the focus groups. Focus groups were audio-recorded, transcribed, and de-identified for analysis.

Data Analyze

[33] Outlined the following steps of thematic analysis: familiarize one’s self with data, generate initial codes, search for themes, examine themes, define/name themes, and confirm themes with a final analysis [33]. These steps guided the researchers in identifying themes that characterized participants’ experiences related to the theatre intervention and their recovery journeys. The first author read focus group transcripts several times before performing line-by-line coding to generate initial codes. Initial codes were organized into a set of initial themes, which were then reviewed by the second author. Following this review, suggestions were made for combining some themes and separating others for clarity and to best represent all participants’ experiences. After developing a final list of themes, member checking was used during follow-up quantitative data collection interviews with participants to ensure that the themes accurately accounted for each participant’s experience of the intervention.

Results

Persevering

Participants reported persevering in the theatre intervention despite difficulties and temptations to quit. All participants juxtaposed aspects of the theatre intervention that were challenging with some sort of personal milestone or achievement. For example, when asked about a time that this project was difficult, one participant with severe social anxiety and PTSD described a rehearsal during which he had a panic attack and how this became an opportunity for him to use his skills and to use the safe social group as a means of overcoming his panic. He describes: My difficulty was when I started to have like a panic attack…they opened up the doors to this dark room with a green parachute pinned to a tent and you got to understand the concept of a big Army tent, ok that’s where you have your chow you see other people, other friends from different Platoons, and then that’s where you hear the bad news or that so and so got hurt or this person got med-aced back to the rear because he got injured so when I was in that tent [in rehearsal] all these memories just come flying back. I told the [art therapist] I’m starting to freak out but I still tried to see if I could control it. So we sit down and then immediately stuff start hitting me and immediately I went back into Iraq so I told her We need to get out of here’ and we went to a different area. When I was in a different area of the theatre, I start looking around and I was looking to gauge myself and I said, well, I was trying to say, Well, I’m freaking out, but she’s not freaking out so, I’m not in danger. She was calm and so I’d tell myself I’m not in danger because she’s calm.

This situation was not planned, rather, occurred because one section of the theatre still had an old set from a play that took place in a circus. The participant was asked to describe how he felt about this unanticipated incident, to which he replied: I think it was positive and negative because I had so much, um, I get to know these guys because I always in practice with them and that’s my goal to know everybody. So I get to know these guys and I get to know the therapists and staff, right? And I used that as my gauge and this was the very, the first time ever to use that. When I’m feeling panicky or I’m feeling fear, I would look in these guys eyes and I would use that as my gauge and I would tell myself, ‘Well if these guys is not freaking out, why am I freaking out So I talk myself down and that was why I say this project is so positive because that was the first time I was ever able to use that and not get panic.

Two other participants echoed this tool of looking to others to persevere despite anxiety and panic. Another commonly noted example of persevering that juxtaposed good and bad was a strong desire to quit the project on opening night due to highly elevated anxiety but an internally felt desire to persevere:

Opening night actually having to go perform in front of people, like, that was the hardest part for me, for the whole thing, you know, that was when I was like, why did I do this? I shouldn’t have done this. I really shouldn’t have done this. And then I did it and I felt great.

Another example of perseverance was described when a participant was able to attenuate his self-reported tendency toward reactive behavior and experienced a positive outcome as a result. This participant was concerned about racism that he was assigned a small role because he was black. He intended to leave the project because of his concern, but unexpectedly a resolution was presented when, the next day, he was given a second role without having shared his concern with anyone. The participant describes: The director decided to give me another monologue and he did that before I said anything to anyone, um, I’d made the decision at that point to stay, I had made a decision to stay prior to telling anyone and before that happened, so then when the change occurred I felt the reward in my choice and my, unchanged approach all’s well that ends well, it worked out well.

This participant shared how he felt his perseverance despite his concern was validated in the end. Quitting the project was a common temptation among participants. One struggled with a desire to quit after a relapse mid-intervention, and another was tempted to quit following an altercation that took place during a rehearsal. Finally, another thought of quitting due to his struggle with disliking authority figures and projecting that dislike onto the director. All of these participants, however, persevered through these mental and emotional challenges and reported a highly positive experience as a result of doing so.

Bonding/being part of a group [36-38].

Data captured via the theme of ‘bonding/being part of a group directly relates to the former theme of perseverance. Participants often reported persevering because of their interconnectedness with other participants they didn’t want to let others down, and each person had a unique and necessary part to play. Due to the nature of this theatre intervention, the commitment to participation in the group was reportedly higher than it may have been in groups that allowed participants to less directly affect each other. As one participant describes: If it had been three nights of bowling three hours a night, I’d have dropped out, you know, because you wouldn’t have missed one more person bowling, but because my part and their part all interacted and depended on each other, it’s like, I got to stay in this.

This interdependency illustrates the power of a theatre group intervention in maintaining participation. The value and benefit of being part of a group was also seen in the above theme of perseverance as participants described observing and modeling each other’s calm demeanors when becoming anxious or panicked. Many participants also mentioned other benefits of being part of a group, including the satisfaction of watching their peers succeed on stage: I never know until it was over that people were thinking of quitting, thinking that they couldn’t do it, but you know to hear them say that but still see how all this came together as a whole we actually pulled it out!

A number of participants also commented on how participation in the project helped them to have more patience with others and also facilitated learning to deal with different personalities. Many also simply noted the enjoyment that came from being part of a group: I think just being around the whole group of people that you know, you know cause we all kind of came together in order to make our characters and everything else it was just a lot of fun I mean, if we would have had a camera rolling at rehearsals, we would have had a hell of a blooper. Another explains the special connection outside of the intervention that he felt as a result of his participation in the group: We all started clicking and, doing that walking down the hallway in our building talking to each other with lines from the play and people are looking at us like what are you guys talking about? Participants described a camaraderie that bonded them together and provided a sense of companionship that they previously did not have, as many were reported loners [38- 40].

The majority of participants talked about the value of engaging in meaningful activity; the benefits they mentioned included time management, a sense of accomplishment, experiencing enjoyment, and having something to focus on. Illustrating the sense of enjoyment and accomplishment gained through participation, one participant describes: I was glad to be part of this, getting up in the morning I looked forward to it. You know, I was a little intimidated by it, but I’d look forward to it, so, every part of it I was glad to be there. Reading the play was really relaxing, and everyone was just kind of in their own element but focused on their lines and not acting out.

Another participant described the benefit of “having something to do to not get high”, and others described experiencing improved quality of life, as the following participant explains:

I don’t have to work anymore, the Veteran’s Administration has deemed me unemployable and asked me not to work anymore but my quality of life diminished I basically sat home and watched “Murder She Wrote,” [laughter] and said, you know, if this is all there is to life, I’m going to not going to make it so I started getting high again. So one of my goals here was to improve the quality of my life, to find something meaningful to do, you know this was not only therapeutic, it was fun and something to do and I got to meet new people and it’s part of that, you know, movement towards being, you know, positive life, you know.

One participant described how the project impacted his daily life, stating, “It gave me something else to take home, uh, it put some very pleasant memories in my mind as opposed to what I was doing before.” Another described “I gained I think a little more practice with my organization and my time management skills” as a result of participating in the project. Similarly, one participant described: I get too involved in, in things up here [points to head] so that kind of helped me sort out, just being in the play gave me something to do a project per se, and it helped me sort out my thinking a little bit because it gave me a reason to remember something pretty delightful, you know, even though it was a little scary it rented some more space here [points to head]so I was focused on remembering the lines and not letting anybody down I had a commitment to the play so, it gave me a purpose, a little bit.

Another participant emphasized the value of having to put skills to use in a real time activity as opposed to just learning new skills in a therapy session: You know, instead of somebody talking to me about it, it’s me and myself and I have to deal with it am I going to freak out or am I going to use what I’ve learned. I like the hands-on part of it and that’s why I think this program should be offered in other VA hospitals Participants’ descriptions of their experiences illustrate how the benefits of engaging in occupation were obtained through participation in this project. Particularly, benefits included having something meaningful to do to replace drug use, improving quality of life through enjoyment and the creation of positive memories on a daily basis, and having opportunities to manage time and put skills to use [41,42].

Performing in front of an audience significantly impacted participants in reportedly beneficial ways. One participant describes: It influenced me it brought my family together and I didn’t know they I mean they, my little sister, she’s kind of the administrator of the family, she got the word out, and um, the response for that was overwhelming for me because this is the first time that my family came together just for me so I was glad to be a part of this it influenced me a lot. This participant went on to say, “it motivates me to really focus on my sobriety and staying in this program cause without this I wouldn’t have got that response.” SS Another participant explained, I think the difference in the other recreation activities was the fact that our friends and family got in on it my family got to come and see a difference in me, my family, my friends, my fellow veterans they got to see me improve, do something positive, in a venue that was, you know, it was just really freaking cool and we were, we were so proud of ourselves. It was kind of like graduating from boot camp, almost.

One participant noted appreciating his son seeing him for something positive he had done rather than something negative. Another compared the rush of applause to an antibiotic injection: You know when you’re so sick no meds will get you over the hump and you have to go get a shot of antibiotics? That is what this was like a little therapy here or there was not enough but getting that rush of recognition and positive feedback all at once after such an intense project was like enough self-esteem boost to get me over the hump and its lasting! Finally, one participant explained that performing in front of an audience gave him the opportunity to confront his fear of crowds that interfered with his daily life, such as preventing him from going to the grocery store due to fear of people: So this was like, okay, I’m on stage, all these people watching me and I’m here and I’m scared to go to the mall, right? So I got an actual opportunity to use that experience. Performing was both an opportunity to gain self-confidence by facing one’s own fears and an opportunity to gain positive recognition from the community, friends and family members a recognition that was described as invaluable.

Self-discovery

Many reported learning more about themselves through the process of “table work”, which consisted of reading through the script several times with different participants reading the roles of different characters and discussing the dynamics and personalities within each scene. Participants reported gaining new insights such as realizing that a room full of people could perceive one interaction in many different ways, or perceive one character’s behaviors and intentions in multiple ways. Many of the participants also described connecting to the story lines and character traits of the roles they were assigned for the performance. One participant describes: The scene where [character 1] was the last person that could stop [character 2] from making a bad decision the last one who could save [character 2’s] life that part really related to me so like, the closeness and like being able to relate to the story those were the rehearsals that were the hardest, cause I’m a really emotional person, I cried during that rehearsal and I started crying during the talk-back after the performance too about that but it was helpful I liked being able to relate to what we were working on.

Participants were able to recognize patterns of behavior and personality traits of their characters that allowed them to see themselves and their own actions more clearly: For me, in rehearsal, saying I’m sorry to [character] reminded me of just exactly the way my divorce went down so that brought back just all the characters seemed to fit in the scheme of things in my past, you know, as far as any difficulties just remembering things it brought on other things I wish I would have said or, you know, it just brought on a lot of things. In some instances, this insight precipitated changed behaviors. For example, this participant describes, “I’ve been on the phone with my ex more recently, just talking communicating more than I have in the past in uh, more positive ways.”

Another participant who was unable to memorize his lines was made aware of the extent to which his memory and concentration had changed and this awareness led to him developing a goal to work on this. He stated, “I had no idea that my memory loss was my concentration was just gone it really is, and uh, I got to work on that.” This participant described gaining more clarity about what he was actually capable of and not capable of at this point in his life and that such awareness could help him direct his attention toward finding ways of changing the latter [43,44].

Discussion

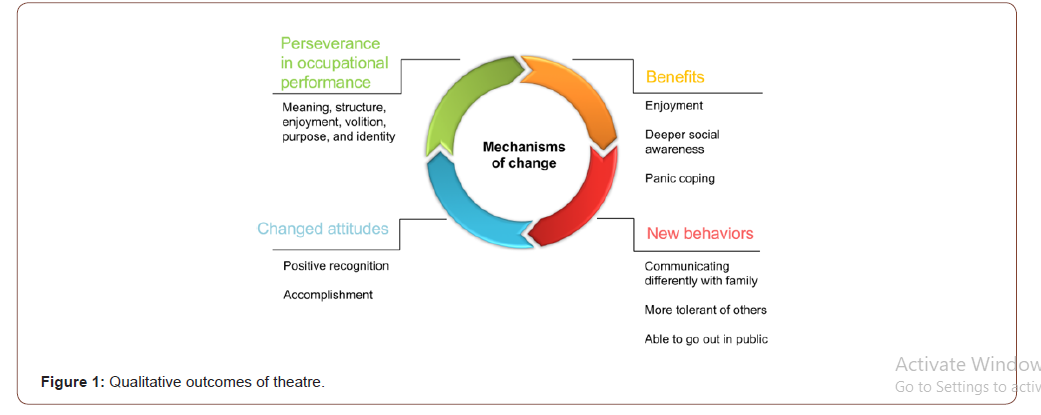

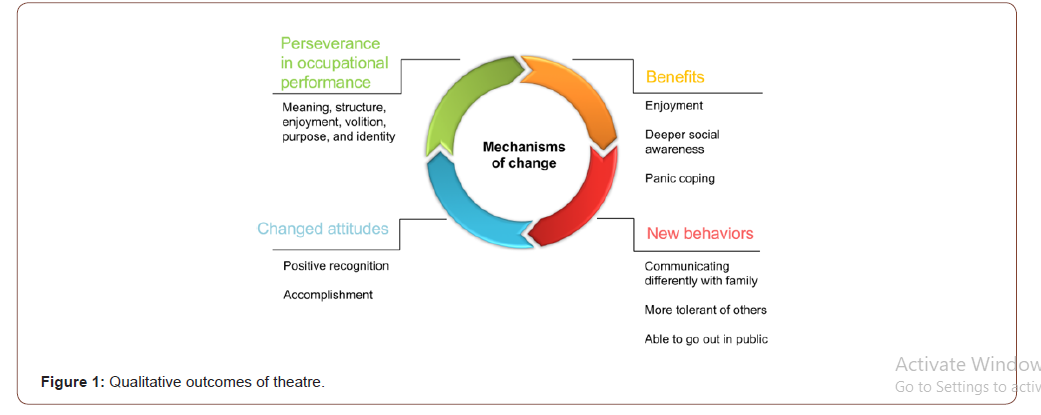

Figure 1 illustrates the inter-relatedness of the above themes and depicts the potential mechanisms of change resulting from participation in a six-week occupation-based theatre intervention.

The interdependency of participants and the relatively high stakes of having to perform in front of a live audience appear to have contributed to the effectiveness of the occupational therapy theatre intervention undertaken in this study. Many of the participants expressed at one time or another strong desire to quit. Many had quit other programs and projects. However, the participants described the theatre intervention as unique in the way that the participants were dependent upon each other not only for success but to avoid having to present an incomplete or unrehearsed performance in front of an audience. This interdependency, participants reported, contributed to their perseverance throughout the project despite the high stakes and temptation to quit.

Because participants stayed and persevered, they had an opportunity for ongoing engagement in an occupation and its many benefits. Participant’s reported that participation in the group facilitated changes such as increased enjoyment in life, the ability to abstain from drug use, improved time management, increased mental focus, and distraction from excessive worrying. These changes mirror some of the known beneficial effects of engaging in occupations such as mental focus, temporal structure, a sense of achievement and purpose, and an opportunity for social bonding [35].

In particular, perseverance led to significant social changes. All participants described how they internalized the positive regard from others experienced during final performances. In addition, they gained insight into their own thoughts and actions as well as how they regard and are regarded by others. Participants reported developing a deeper social awareness through the process of table work they gained new insights about how different people interpret social exchanges in different ways. They also noted being more tolerant of others as a result, both inside and outside the theatre group. Participants identified with the characters in the play and were able to gain better self-awareness by comparing and contrasting themselves with their characters. They reported that after gaining understanding of the lives of their characters, they were able to observe their own lives more objectively. Finally, participants reported looking to others in the group to decipher whether or not they were safe, allowing them to abate the onset of panic attacks.

All of these benefits contributed to changed behavior and thus provide some details about the mechanisms of change that occurred as the result of participating in the theatre intervention. Participants were able to go into social environments without having panic attacks, improve communication with their families and friends, and developed a more affirming sense of self.

Limitations

This study is limited in several ways. While large sample size and generalizability of findings are not the aims of qualitative research, data from a larger number of participants would help the researchers determine whether the themes found in this study illustrate something inherent in the nature of the theatre intervention or are more specific to this study’s unique participants and interventionists. There is a risk for selection bias as participants volunteered to participate in our intervention. Generalization of these findings would benefit from a follow-up study using randomization and a comparison group. Additionally, data were collected via a single focus group with each set of participants and therefore reflect the participants’ moods, experiences, and thoughts at only one point in time rather than combining a variety of feelings and perceptions of the intervention collected at multiple points in time when participants may have felt differently or been differentially influenced by contextual factors unrelated to the study. Future research should include repeated measures to establish a temporal relationship between the intervention and subsequent outcome measures. Finally, it is possible that the participants did not respond honestly because they may have wanted to portray a certain image in the presence of the principal investigator who was involved in the study, or may have been affected by the social setting/context in which focus groups took place [36-44].

Conclusion

Researchers demonstrated that a six-week occupation-based theatre intervention has the potential to engage and retain veterans in early SUD recovery and improve social and occupational participation over time. Qualitative findings suggest that the nature of the intervention specifically the fact that it assigns a unique and necessary role to each participant encourages ongoing participation in the intervention that results in participants experiencing occupational gains. Specifically, this intervention may produce positive changes in social and occupational participation over time by enhancing social skills and time management, improving self-image, providing cognitive challenges and illuminating areas of cognitive decline, and increasing efficacy regarding individual ability to apply previously learned therapeutic tools. Further research is needed to examine the effectiveness of the proposed theatre intervention and facilitate implementation and fidelity.

To read more about this article..Open access Journal of Journal of Complementary & Alternative Medicine

Please follow the URL to access more information about this article

To know about Open Access Publishers