Authored by Norbert Schwarzer

After it became clear that Quantum Computers are more powerful than

originally thought [1], the question popped up whether one could find

the most fundamental form of a Turing machine based on Quantum Theory.

Doing this job in a very comprehensive manner, we found that the

deepest layer for the Quantum Computer was not to be found inside the

theoretical apparatus of Quantum Theory. Surprising as this may be, it

is

the General Theory of Relativity which “contained it all”. We found that

an extremely simple solution of the Einstein-Field-Equations, using

pairwise

dimensional entanglement, sports the principle structural elements of

computers [2]. We will derive these structural elements and show that

the

classical computer technology of today and even the quantum computers

are just degenerated derivatives of this general solution. In this short

paper

we will discuss thin-film technology- and smart material-options

potentially helping us to one day realize the general computer concept.

As often

spin is seen as THE one possibility to realize Quantum Computers, we

will try to find a metric understanding of the concept of spin.

Introduction

In order to keep this paper as brief as possible we only introduce the essentials. These essentials are a set of new solutions to the Einstein-Field-Equations as given in [2-34]. Among these solutions, we also found candidates with the potential to construct Turing or Turing-like machines [35] having special bits apparently even more powerful than quantum bits.In [34] we gave a time dependent (oscillating) solution, which represented a metric satisfying the Einstein-Field-Equations [36,37] for the case of an arbitrary 2-EQ-bit (EQ=Einstein Quantum) processor. Here we intend to investigate these solutions with respect to possible extensions regarding more bits plus timidly start to explore the question of storage and machine design in connection with the quantum property named spin.

How to Quantize Solutions of the Einstein-Field-Equations

As the introduction to the method of quantizing metric solutions of the Einstein-Field-Equations is quite lengthy and was already presented in a variety of previous papers [2-34], we refrain from presenting it here again. Instead, we will only give a brief recipe:1. We consider space as an ensemble of properties.

2. These properties could just be degrees of freedom and thus, dimensions, which are subjected to a Hamilton extremal principle.

3. This leads to the Einstein-Hilbert-Action [36] and subsequently to the Einstein-Field-Equations [36,37].

4. Time seems to take a special place among the properties as it is not such a property itself but consists of all other properties’ internal changes and variations. Applying the Einstein-Field-Equations on the internal degrees of freedom of each single property as a one-dimensional space (c.f. [14]), gives exactly 6 solutions [17] among which we always also find oscillations. These internal periodic processes (changes) inside each property or dimension are realized as time from an external observer… time, which itself forces other properties to change. Thus, starting as an internal property (solution) within each dimension, time not only is change, but also brings change about. Apparently, time is the most fractal and self-similar thing there is in this universe.

5. Now, however, we have the interesting situation that solutions to the Einstein-Field-Equations are not necessarily unique. Derived from the Einstein-Hilbert-Action as an extremal principle, the starting quantity is the so-called Ricci scalar R, being the essential kernel of this action. This results in a metric solution to the Einstein-Field-Equations, being subsequently derived from the Einstein-Hilbert-Action. Most interestingly, there are also infinitely many solutions to just one given Ricci kernel. Just as an example, one might take the flat Minkowski space and the Schwarzschild vacuum metric [38]. Both have a vanishing Ricci scalar R=0, but while the first describes empty space, the second, even though being a vacuum solution, contains a gravitational “object” of spherical symmetry. And yes, this all comes out from a variational kernel of R=0. Thus, so our conclusion, there seem to be quite some degrees of freedom regarding the choice of metric solutions to just one Ricci scalar curvature.

6. Tickling metric solutions with respect to this degree of freedom, which is to say to perform a variation (or transformation) of metric solutions, thereby treating the Ricci scalar as a conserved quantity, gives us classical quantum equations and thus Quantum Theory.

Essentially one finds Quantum Gravity as transformations to metrics solving the Einstein-Field-Equations:

Here we have: Rαβ,Tαβ the Ricci- and the energy momentum tensor, respectively, while the parameters Λ and κ are constants (usually called cosmological and coupling constant, respectively). These are the well-known Einstein-Field-Equations in n dimensions with the indices α and β running from 0 to n-1. The theory behind is called “General Theory of Relativity”.

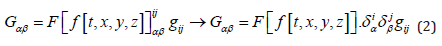

Thereby we can use external or internal degrees of freedom. While in most of our previous papers (e.g. [33] as this is most compact) we concentrated on external or wrapper-like transformations of the kind:

we also introduced inner or Killing-like approaches in [39]. Most interestingly, these inner Quantum Gravity transformations led to the Dirac equation [40].

In conclusion we might state that Quantum Theory is just the inner degree or fluctuation of metric solutions to the Einstein- Field-Equations.

The interested reader will find a compact mathematical presentation of the above recipe in [33].

The 2-Bit EQ or Einstein Quantum Computer

It is a common misinterpretation of the original Turing work [35] that many people assume Turing has suggested a digital machine. In fact, his approach contained a computer machine with an arbitrary real basis, but Turing considered the use of integer numbers to be the most appropriate way to realize his machine and so he suggested the digital form. In principle, however, his concept was not necessarily restricted to a digital basis.As we found that the Einstein-Field-Equations are the most principle building blocks of this universe, we want to find solutions to these equations, which – at least in theory – allow us to build a computer. It is obvious that such a system requires a circuit time, governing the whole system and two additional properties allowing for storage and operations.

The corresponding evaluation was already performed elsewhere [2,34,41]. For convenience we here repeat it briefly.

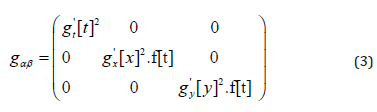

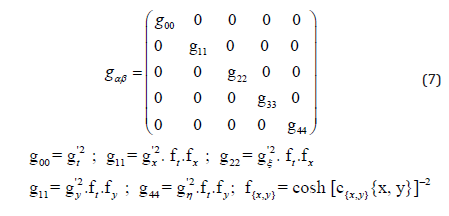

By applying a metric approach of the kind:

we will find a general solution to the Einstein-Field-Equations [1, 3] with the function:

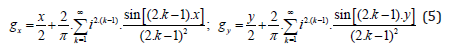

Thereby Λ denotes the cosmological constant. Please note the matter and anti-matter character of our solution (4). The functions gx and gy are arbitrary and could be used for operations/data of any arbitrary form. In order to assure digital outcomes to the metric components g11 and g22, standing for the second and the third diagonal metric component, respectively, we construct Fourier series of the kind:

We see that the system constructed above has everything a most simple 2-bit “processor” requires. It has the necessary two bits and it has a periodic function defining a cycle time. What we also need is a way to store information. Applying the Turing approach [35], we might just couple in certain add-on dimensions playing the role of these storages, or, if using the Turing picture, playing the role of the tape of our EQ-Turing machine (EQ=Einstein Quantum). A simple extension of the metric (3) of the form:

might help us to solve the problem for at least one storage process by entangling the coordinates x-ξ and x-η. A second set of solutions can be constructed via the following approach:

and would bring the same result in a slightly variated form (read and write options).

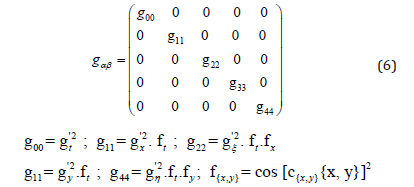

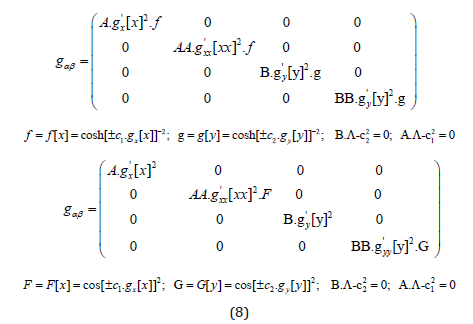

We recognize the application of the pairwise coupling or entanglement of dimensions as elaborated in [42]. Substituting ξ=xx and η=yy we can directly obtain the solutions from [34] with the following sub-metric of the components 1-4:

The total metric shall be given then either as:

or (careful with the constant H and the function H[t]):

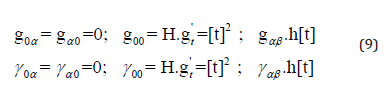

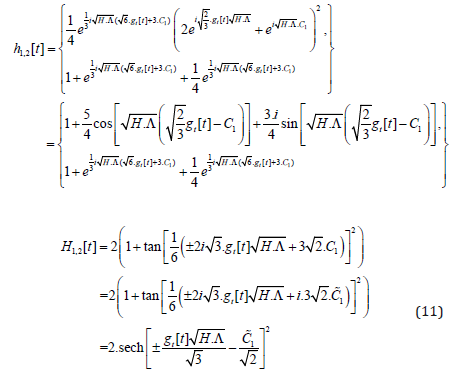

With the help of the results of [43,44] we can solve the subsequent Einstein-Field-Equations and find:

While in the case of H[t] and an assumed gt[t]=t we obtain a bell shaped function, meaning that the whole system appears and disappears after a while (it only virtually exists), we now have a stable oscillation in the case h[t] (Figure 1).

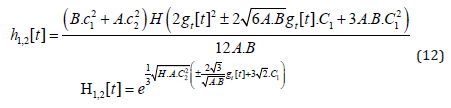

Things change dramatically in the case Λ=0, where the Einstein- Field-Equations require the following rather different solutions for the cycle-time functions h[t] and H[t], reading:

In addition, we have the functions f, g, F and G as before plus the boundary condition for the constants A, B and ci as follows (Figure 2):

This time the approach gt[t]=t does not lead to oscillations for h[t] but still we can achieve time-periodic behavior via H[t] and gt[t]=i*t.

Using the results from above it is easy to construct the metrics for higher bit-systems. For instance, the total metric for an 8-bit case would have to contain 17 dimensions and could generally be given as:

We have the two options for pairwise coupling (entanglement), namely:

By the structure given in (14), it can easily be seen how the extension to any number of bits can be achieved.

The Metric Understanding of Spin

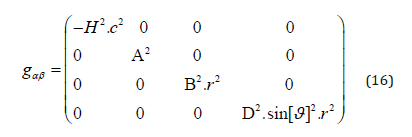

Thin film technology has allowed to create so-called quantum dot structures, sporting typical quantum properties in an applicable, which is to say steerable manner. As it is widely assumed that the realization of a Quantum Computer is achievable by using the quantum property spin, we require an Einstein-based, which is to say, metric understanding of this property.Starting with the following metric:

and demanding a vanishing cosmological constant

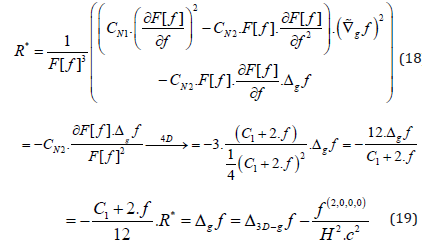

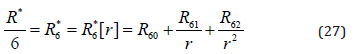

we have shown in [45] that the resulting Ricci scalar R* of the transformed metric using recipe (2) and the corresponding 4D wrapper-function F [f=f [t, r, ϑ, φ]] =(C1+f) ² reads:

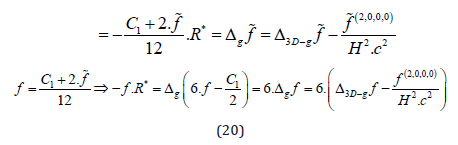

Now we substitute as follows in (19):

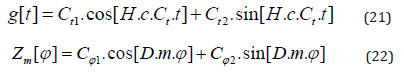

Applying the separation approach f[t,r,ϑ,φ]=g[t]*h[r]*Y[ϑ]*Z[φ] with the previously used separation parameters Ct and m (compare for the sub-section ”Flat Space Situation” in [33]) in (19) gives us the following immediate solution for g[t] and Z[φ]:

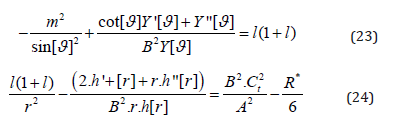

The two remaining differential equations can be constructed as follows:

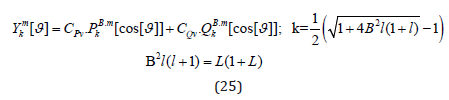

While the first equation of the two gives the usual solution with the Legendre polynomials, as also known from the Schrödinger hydrogen solution [46] only in slightly generalized manner (watch the asymmetry-parameter B):

we have a rather non-Schrödinger-like solution with respect to the radius coordinate in the case of R*=0:

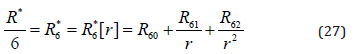

Regarding the angular functions within f […] we might assume that, just as known from the Schrödinger hydrogen problem, we have the conditions L= 0,1,2, 3, … and -L ≤ B*m ≤ L. However, it was shown in [33,45] that we also have options for singularity free solutions with L= {1/2,3/2,5/2, …}. We realize that our solution has no main quantum number as the classical Schrödinger solution does. However, it was shown that such a number appears with the introduction of a potential V[r]~1/r (the classical Schrödinger way), the breaking of symmetry ([33] or appendix of [45]) or the assumption of a boundary in r (e.g. [33]). As we are here only interested in the half-spin solutions, we simply apply the classical Schrödinger way and start with an approach for R* as follows:

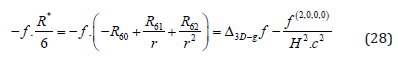

Setting this into the last line of (20) gives:

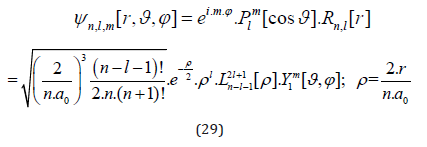

Now the classical Schrödinger wave function [46]:

directly solves our Quantum Gravity equation (28) for static cases where f does not depend on t.

The constant a0 is denoting the Bohr radius with (me=electron rest mass, ε0=permittivity of free space, Qe=elementary charge):

The functions P, L and Y denote the associated Legendre function, the Laguerre polynomials and the spherical harmonics, respectively.

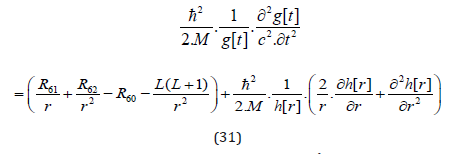

The extension to time-dependent f according to (28) is simple. However, in order to avoid too many parameters and work out the connection to the classical Schrödinger evaluation, we set H=A=B=D=1. By using the results from above we can reproduce the Schrödinger hydrogen problem from (28) being changed to:

Thereby we have introduced the term

(reduced Planck

constant squared

(reduced Planck

constant squared  divided by mass (M) in order to truly mirror

the classical Schrödinger equation. Multiplying with M would give

us:

divided by mass (M) in order to truly mirror

the classical Schrödinger equation. Multiplying with M would give

us:

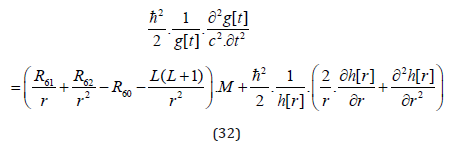

and connects the mass M with the curvature terms R6 and the momentum.

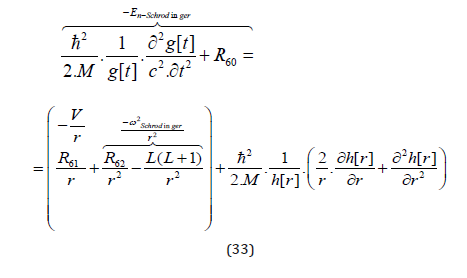

Comparison of (31) with the Schrödinger derivation (e.g. [46], pp. 155) and if R60 is a constant gives us:

Using the result for g[t] from above, which is to say:

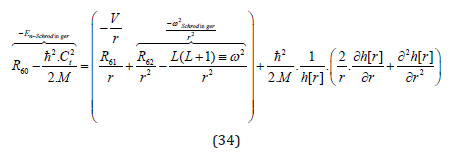

we can now rewrite (33) as follows:

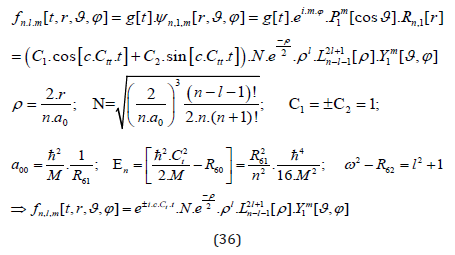

and thus, get the classical radial Schrödinger solution for the radial part of f […]:

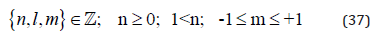

Regarding the conditions for the quantum numbers n, l and m, we not only have the usual:

but also found suitable solutions for the half-spin forms as discussed above and derived in the appendix. The corresponding main quantum numbers for half-spin l-numbers with l=1/2, 3/2, … are simply (just as before with the integers) n=l+1=3/2,5/2,7/2, l….

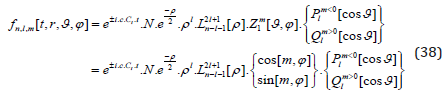

It should explicitly be noted, however, that the usual spherical harmonics are inapplicable in cases of half-spin. For {n, l, m} = {1/2, 3/2, 5/2, 7/2, …] the wave function (36) has to be adapted as follows:

Thereby it was elaborated in [45] that in fact the sin- and the cos-functions seem to make the Pauli exclusion (s. [47]) and not the “+” and “-“ of the m. However, in order to have the usual Fermionic statistic we can simply define as follows:

As discussed above and derived in [33] plus the appendix in [45], the resolution of the degeneration with respect to half-spin requires a break of the symmetry, which we achieved by introducing elliptical geometry instead of the spherical one.

Assuming an omnipresent constant curvature R60 does not seem to make much sense in our current system and thus, we should set R60=0. Doing the same with the curvature parameter R62 just gives us the usual condition for the spherical harmonics, namely ω2 = L(1+ L) = l2 +1.

Thus, we result in:

This metrically derived “hydrogen atom”, which also has half-spin solutions, was intensively discussed in [45]. Here we concentrate on l=1/2 situations, which – so the immediate association when illustrating the corresponding spatial distortion – not only directly explain the Pauli exclusion principle but also allow for a structural understanding of the half-spin solutions.

Only in order to keep things familiar and potentially compare with the classical integer hydrogen states (40), we keep the normalization and the scale of the Bohr radius a0. One might perhaps call the resulting objects “half-spin hydrogen atoms”. With only one exception (Figure 5) we start with the general setting of m>0 ( → Z[φ]=cos[m*φ]). It can easily be seen with the simplest half-spin states (n=3/3, l=1/2 and |m|=1/2) as presented in Figures 3&4, that the gross of deformed space-time is to be found on the right hand side of the x=0-plane. Now choosing n=3/3, l=1/2 and m=-1/2 and applying the statistic rule defined in (39), leading to Z[φ]=sin[m*φ], gives us a concentration of deformed space-time on the other side of the x=0-plane (Figure 5). It appears intuitive to assume that the combination of objects with deformation maxima on the left and right (anti-parallel spin) is easier than the combination of objects having the maximum deformations on the same sides of the x=0-plane (parallel spin combination). We might see this as the geometric manifestation of the Pauli exclusion principle [47].

Acknowledgements

None.Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

To read more about this article....Open access Journal of Material Science

Please follow the URL to access more information about this article

No comments:

Post a Comment