Authored by John Handley*

Short Communication

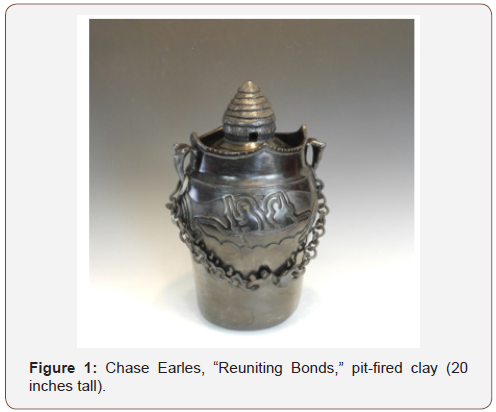

In collaboration with the Caddo Mounds Historic Site in Alto, TX (CMSHS), Stephen F. Austin State University presented the exhibition “Caddo Contemporary: Present and Relevant,” January 24 – March 24, 2019 at the Ed and Gwen Cole Art Center @ The Old Opera House. The exhibition highlighted the work of seven living Caddo Nation artisans: Wayne Earles, Chad Earles, Chase Earles, Raven Halfmoon, Yonavea Hawkins, Jeri Redcorn, and Thompson Williams. The exhibition was important for two specific reasons: It was the first exhibition that highlighted the work of living Caddo artists working in traditional and/or adapted art forms. And, it was a first for contemporary Caddo art displayed in Nacogdoches, TX, the home of the Caddo Nation for perhaps a thousand years or more before they were forced off their land in the early 1800s and relocated to Oklahoma.Prior to the exhibition, scholarship on the Caddo Nation has focused on their remarkable, albeit sometimes painful, past. Their history, art, language and dance have been explored in books and journal articles. Although this work can be applauded, there has been little to no forward-looking work published on the descendants of these tribes. This exhibition was a first step towards remedying such oversight by seeing first-hand the present day and relevant work in.

The idea for an exhibition that explored the Caddo Indians began in 2016 when I engaged in a dialogue with Rachel Galan, the assistant director and educational interpreter for the CMHS, a prehistoric village and burial site. Ms. Galan pointed out the difficulties in presenting historic works of art as the majority held in museum collections were funerary in nature, having been excavated from sacred sites against the wishes of the Caddo people. With that option off the table, she identified a group of living artists in Oklahoma whose work had never been highlighted in an exhibition. We eventually made the trip to Oklahoma where we met initially with three of these artists.

One of the first questions to be addressed was that of curatorship—who was going to select the pieces for the exhibition? Who was going to interpret them? We concluded that each participating artist would select the pieces they wanted to exhibit. We felt this was the right decision based on the fact that there has been a history of curators and historians who were eager to talk about the Caddo as if they were not capable of telling their own story. Thus, they were able to speak for themselves through their art and artist statements. The end result had a great impact for the Caddo people and visitors to the exhibition. Also included was a fullcolor exhibition catalogue, designed by Chase Earles, that featured key pieces from the exhibition along with artist statements.

What is significant for these Caddo artists is that their traditional artistic methods had not been well preserved, leaving them to be rediscovered. One such artist is Jeri Redcorn, who initially had no idea of the ceramic traditions of her tribe. Working with archeologists and museum curators over many years, she rediscovered traditional ceramic methods and designs. Today her work is applauded and several of her pieces are in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution. One of the youngest of the artists is Raven Halfmoon. Autobiographical in nature, her work draws on her experience as a Native American woman, with large ceramic sculptures bearing titles like “You Don’t Look Native” of “Do You Speak Indian?”

In addition to the artwork on display, the collaboration featured special programs, such as storytelling and dance performances by Kricket Rhoads-Connywerdy, an enrolled member of the Caddo and Kiowa tribes of Oklahoma. She has been telling Kiowa and Caddo stories in Oklahoma, the United States and internationally for over two decades. She performed, along wither daughter, in traditional Caddo dress of Kiowa buckskin and cloth.

The documentary film, “KOO-HOOT KIWAT: The Caddo Grass House” by Curtis Craven was also presented as part of the exhibition. The film chronicles the building of a traditional Caddo grass house on the grounds of CMSHS. A Caddo tribal elder and his apprentice returned to their ancestral homeland to direct a group of enthusiastic local volunteers in the design and construction of the grass house. Phil Cross, the Caddo elder and project architect, is perhaps the last of his tribe with the knowledge of this nearly forgotten practice. By building the house on the land of his ancestors, he passed his knowledge to the next generation and beyond. Several people who attended the screening of this film had worked on the construction of the house and were featured in the film. Sadly, the grass house was destroyed in a devastating tornado on April 13, 2019, though there are plans to reconstruct it again in the future.

To read more about this article.. Open access Journal of Archaeology & Anthropology

Please follow the URL to access more information about this article

To know more about our Journals....Iris Publishers

No comments:

Post a Comment