Authored by Hazim AlEid*,

Abstract

Vocal folds dystonia and total vocal folds paralysis in Xeroderma Pigmentosum Type-A (XPA) are considered rare clinical entities that have been recently described in few case reports from the Japanese literature. We report an 11 years old boy with XPA and seizures and history of frequent emergency room (ER) visits to different local hospitals for recurrent inspiratory stridor which was treated as “croup” since the age of 10. The child was brought into our ER for the first time with recurrent, severe stridor and was admitted as a severe case of “croup”. He was treated for approximately two weeks with only minimal improvement. Laryngoscopy showed normal vocal cord appearance with no signs of inflammation.

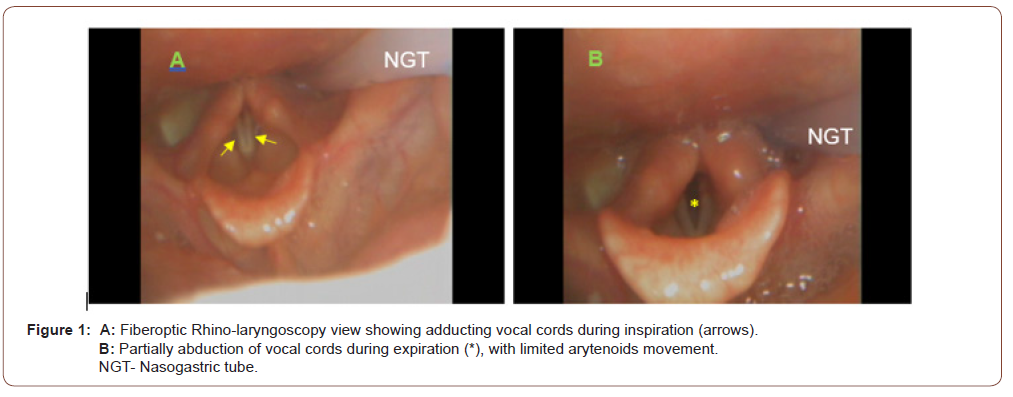

Shortly after discharge, he was re-admitted with stridor, which was noticed to be episodic, exacerbated by irritation, excitation and post oral feeding. Stridor subsides completely during sleep. Repeated laryngoscopy was performed to investigate other potential causes of stridor. Flexible rhino-laryngoscopy showed paradoxical vocal folds movement with glottic closure during inspiration and limited glottic opening upon expiration which is consistent with laryngeal dystonia. This case report represents the history, physical examination and the follow up findings in this XPA young boy with unusual presentation with stridor and rare association with vocal cord dystonia. Additionally, it raises the question of the validity of considering early tracheostomy in such cases to avoid repeated non-otherwise avoidable life-threatening stridorous attacks.

Keywords: Xeroderma pigmentosum; Laryngeal dystonia; stridor; Paradoxical vocal fold movement; PVFM; Tracheostomy

Case Report

The patient is 11 years old Saudi boy who presented for the first time to the neuroscience center at 3 years of age as a referral for work up of seizure disorder and ataxia. He was born by normal uncomplicated vaginal delivery and had normal early infancy. At the age of 4 months, he was noted to become sensitive to sunlight with skin sunburns and xerosis progressing in severity with time. He, then, started to show milestone developmental delay. Seizures developed at 3 years of age that was controlled well with anticonvulsants. Ataxia and regression of milestones progressed with time until he became totally bedbound. He had characteristic skin lesions in the form of diffuse skin freckling and telangiectasia with sunlight sensitivity. EEG revealed severe generalized cortical dysfunction of nonspecific etiology. Brain MRI revealed generalized brain atrophy.

Chromosome study confirmed Xeroderma pigmentosum type A at 8 years of age. Reviewing his family history, the parents were first-degree cousins; two younger brothers were diagnosed with milder form of XPA. There was no family history of epilepsy. In the first presentation, patient came with the main complaint of noisy breathing and shortness of breath associated with “cold” symptoms and low-grade fever without vomiting, diarrhea or seizure activity. Vitals were as follows: temperature 38°C, respiratory rate 28 per minute, oxygen saturation 95% on room air, heart rate 105 bpm and blood pressure 100/60 mmHg. Patient looked alert, mildly dehydrated and in mild respiratory distress with stridor. General examination showed microcephaly with no dysmorphic features, scleral telangiectasia, Normal Ear, Nose and Throat examination. He appeared to be mildly tachypneic. Neck was stiff with no lymphadenopathy or masses detected. Chest and abdominal examination was unremarkable.

Neurological exam demonstrated spastic quadriplegia, brisk deep tendon reflexes along with contracted and fixed upper and lower extremities. Spine was stiff from cervical to lumbosacral segments. Skin exam revealed diffuse freckling and telangiectasia. There were no bed ulcers. Laboratory findings and imaging studies were all within normal Laryngoscopic examination was reported as “normal” vocal cords. Considering the aforementioned findings, the preliminary diagnosis was croup and the patient was treated accordingly with racemic Epinephrine and IV fluid. Respiratory distress and stridor gradually improved, and he was discharged home in five days in a stable condition. Ten days later, he came back to emergency room with the same complaint of stridor and difficulty in breathing. Treatment was initiated again with racemic Epinephrine and admitted to pediatric ward to continue the same management.

During hospitalization, however, it was noticed that stridor used to be triggered and exacerbated mainly by irritation and agitation and obviously during oral feeding time and was observed to subside totally during sleep. Chest X-ray and all repeated laboratory work up were within normal limits. It is worth mentioning that the patient’s O2 saturation was normal, even during episodes of stridor. Flexible, fiberoptic rhino-laryngoscopic exam (Figure 1) showed normal vocal cords anatomy with no edema or mass. However, there was paradoxical vocal cords movement with glottic closure during inspiration (Figure A), and limited glottic opening during expiration (Figure B). Findings were consistent with laryngeal dystonia responsible for the recurrent episodes of stridor. Findings were discussed with the parents in details and tracheostomy was advised in the near future. Family, however, refused the procedure but agreed to continue follow up with ENT, Neurology and general pediatrics services in outpatient clinics. Follow up laryngoscopic exams (twice) within three months showed similar findings. 6 months later, patient presented to ER with severe stridor and life-threatening respiratory distress requiring intubation and PICU admission. Informed consent was obtained from parents for tracheostomy, which was done without complications. Patient was scoped again after tracheostomy to check for any changes, and further decrease in vocal cords mobility to barely flickering movement was noted. Patient was discharged home with tracheostomy to follow up closely.

Discussion

Stridor is the distinctive, harsh and high-pitched sound resulting from the turbulent flow of air while passing through a narrowed segment of respiratory tract. It usually signifies the presence of upper airway obstruction and may progress to potential respiratory distress. Stridor can be classified according to the age group. In early infancy, stridor could result from congenital laryngomalacia, vocal cords paralysis, subglottic stenosis, hemangioma, webs, cysts, and papilloma. In pediatric and adolescent age groups, etiology of stridor differs and may be the result of juvenile onset of recurrent respiratory papillomatosis, foreign bodies, hypocalcemia, cystic fibrosis (CF) and Wagner’s granulomatosis. Infectious diseases may contribute to the etiology of stridor, commonly herpes simplex, candidiasis and infectious mononucleosis. Laryngotracheobronchitis (croup) caused by respiratory Syncicial Virus (RSV) and epiglottitis due to Haemophilus influenza are common etiology of stridor in infants and children, as well. Stridor may result from neoplasms, such as Hodgkin’s disease and thyroid masses. Myasthenia gravis may occasionally be associated with stridor [1].

Xeroderma pigmentosum (XP) is an autosomal recessive disease characterized by hypersensitivity to sunlight, abnormal pigmentation and predisposition to skin cancer [2,3]. In addition to the cutaneous manifestation, neurological abnormalities (loss of hearing, tendon refluxes, walking impairment, intellectual impairment) are seen in 20% of XP [4].Cell fusion analysis has identified seven complementation groups (A-G) of excision repair [5]. Patients with Xeroderma Pigmentosum group A (XPA) generally show the most severe symptoms and signs of the disease [6]. We describe a case of XPA with Laryngeal dystonia that resulted in recurrent episodes of stridor and life-threatening respiratory distress requiring intubation and tracheostomy. Laryngeal dystonia secondary to paradoxical vocal folds motion (PVFM) may be characteristic of this disorder. The vocal folds are innervated by the recurrent laryngeal nerves, which are branches from the Vagus nerves originating from the medulla oblongata. During inspiration, the vocal folds normally should abduct. However, in some cases, like in our XPA patient, the opposite might occur, and the patient will have adduction of the vocal folds during inspiration resulting in inspiratory stridor.

The specific finding of PVFM is considered relatively a new clinical entity associated with XPA in the medical literature with multiple attempts by researchers to explain its mechanism. PVFM has been defined by Andrianopoulos et al as an “entity characterized by inappropriate closure of the vocal folds during inhalation, resulting in intermittent respiratory obstruction and stridor” [7]. It has been linked mainly to non-organic causes and psychiatric disorders, as Mary J Sandage, et al. [8] mentioned that the line to differentiate between a functional or organic disorder is unclear [8].

Stephen Maturo, et al. [9] mentioned in their large case series of 59 cases of PVFM that the female to male ratio was 3:1 and the speech therapy was effective in 63% of cases. They reported, in addition, that many of these cases might have an underlying psychiatric disorder [9]. PVFM is still not fully understood, and many patients may carry the diagnosis of asthma. When compared with asthma, PVFM has a number of distinctive features including inspiratory stridor, rather than expiratory wheezing, and the lack of clinical response to bronchodilators or corticosteroids [9]. The neuropathological study done by Röyttä M, et al. [10] showed “marked loss of neurons in the basal nucleus of Meynert, the substantia nigra, the cerebellum, medulla and spinal cord. Diffuse loss of neurons was noted in the cerebral cortex and in the deep cerebral nuclei” [10].

This loss in the substania nigra neurons found on autopsy of XPA patients was the explanation used by Rie Miyata in his case series of three XPA patients in their teens with stridor and PVFM, as he attributed the cause of stridor to the damage of the dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra as in extrapyramidal disorders. Two of these cases demonstrated some improvement of the symptoms after administration of low dose of levodopa and the other had some worsening of motor functioning and the treatment was stopped [11]. In a case series by Worely, et al. [11] they reported 3 cases of Laryngeal dystonia in 3 Cerebral palsy cases, one of them was being treated with periodic Botulinum Toxin (BTX) Type A into the vocalis muscle alternating the sites in a way to avoid tracheostomy (the latter was refused by the parent) fortunately that patient outgrew her Laryngeal dystonia after 2 years of initiating the treatment and did not need further intervention [12]. Nevertheless, in our patient the trial of levodopa was declined by the pediatric neurologist as this treatment is still under trials and not approved by the corresponding medical societies. And BTX injection was not amenable.

Reviewing the literature of PVFM or stridor in XP patients, it was exclusively established in XP type A. Only three papers were found; one paper described a case of total vocal cords paralysis in one XPA patient in which the patient required tracheostomy after intubation in a life threatening stridorous attack [13], the other two papers presented cases very much similar to our patient. One of them reported three patients by Ayako Muto, in which One of the 3 cases ended up requiring tracheostomy after intubation, and the other two cases were siblings whom their parents were refusing the idea of tracheostomy [14], while the third paper described three XPA patients with PVFM who were treated with levodopa as mentioned earlier [11]. It is worth mentioning that all of these case reports are from Japan.

All of these patients were in their second decade at presentation with the youngest being 12 years and 3 months old [11]. As far as we know from these data, our patient is considered the youngest to develop laryngeal dystonia due to PVFM in association with XPA, which has started at the age of 10. The question that is worth raising is, would determining tracheostomy in the early course of the PVFM in XPA patients help in reducing the rate of life threatening attacks of stridor in the affected patients, reducing the possibilities of complications and unfavorable events ( intubation and its complications, incidence of ventilator acquired pneumonia, prolonged ICU admissions,..). Given the relatively scarce worldwide reporting and discussion of such cases, finding a definitive answer is yet to be debated.

Summery

Laryngeal dystonia secondary to PVFM is a poorly understood condition which appears to be life threatening in XPA patients. To date, there is no definitive approved treatment of this disorder. The onset can be insidious and early in childhood. Laryngeal dystonia should be suspected in XPA patients who present with asthma- or croup-like symptoms that do not improve with standard treatment. Otolaryngology consultation is strongly recommended early in the presentation to assess the patient thoroughly with fiberoptic laryngoscopy. Patients should be kept on close follow up as they might progressively get worse over time and require tracheostomy in order to secure the airway as in our patient.

One final point that may deserve further discussion and additional research is whether PVFM in XPA patients would benefit from early tracheostomy after the start of stridorous attacks, in order to reduce the possibilities of Life-threatening respiratory events.

To read more about this article....Open access Journal of Otolaryngology and Rhinology

Please follow the URL to access more information about this article

To know more about our Journals...Iris Publishers

No comments:

Post a Comment