Authored by Michael Schirmer*,

Opinion

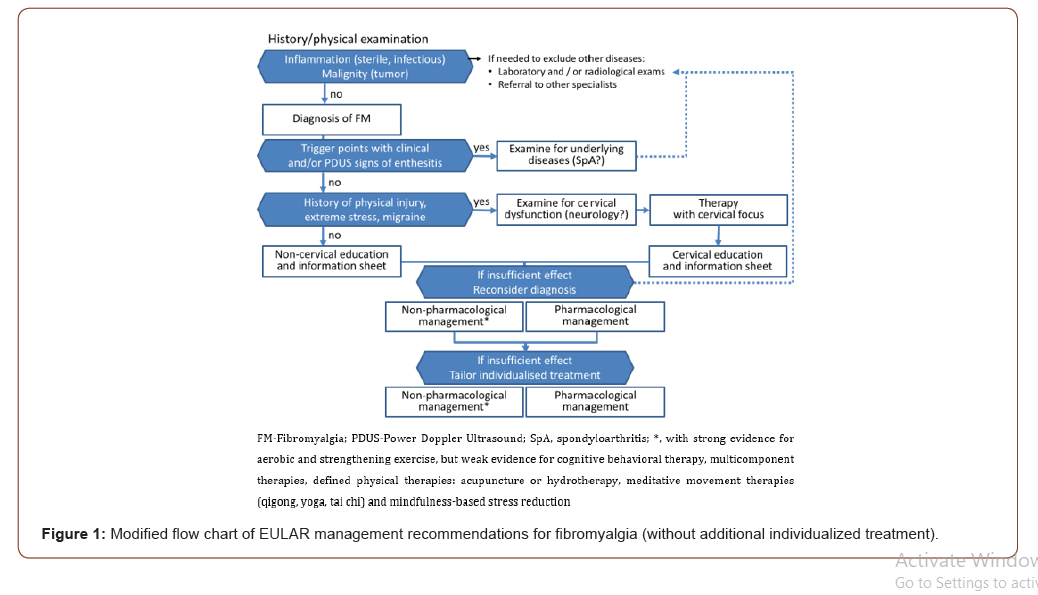

In the general population, the prevalence of fibromyalgia (FM) is estimated as high as 1.8% [1]. Rheumatologists, neurologists, psychiatrists, and other disciplines may be involved to cover the full spectrum of a biopsychosocial model to care for these patients. With high health-care use for up to 10 years before diagnosis [2], FM is considered as an ongoing challenge: (1) different criteria are used for diagnosis – sometimes even without any objective biomarker included, (2) outcome criteria are not widely used in clinical practice and (3) new and promising therapeutic concepts and strategies are missing. An interdisciplinary team last updated the EULAR management recommendations in 2016, recognizing the need of further updates after 5 years [3]. This personal “opinion” summarizes some aspects considered important for the management of FM in clinical routine (Figure 1).

Aspect 1: Concerning Diagnosis of FM

Criteria for the diagnosis of FM are still under discussion [4,5], and a final international consensus is missing. The EULAR task force notes that “laboratory and / or radiological exams and referral to other specialists” is recommended “if needed to exclude treatable comorbidities” [3]. Given the high impact of FM for the life quality of FM patients, I completely agree that differential diagnoses have to be ruled out before diagnosing FM. Besides - according to our experience – diagnosis of FM must be reevaluated from time to time to avoid lack of treatment of underlying diseases as a result of missing diagnoses other than FM [6].

Aspect 2: Proposing subtyping of FM

Already in 2009, Wilson et al. proposed a heterogeneity within FM patients, identified by variable tender point severity ratings [7]. In view of the available treatment approaches, I fully agree with this concept of subtyping FM to better examine therapeutic approaches for each subtype in the future.

Aspect 3: With Trigger Points as Biomarkers?

Trigger points have been included into some approaches to diagnose FM, and therefore may be considered as a diagnostic biomarker for FM. As a consequence, trigger points should be examined more carefully: First, patients should be screened for inflamed sites by distinct clinical evaluation [8] and - if in doubt - by power Doppler ultrasonography, which detected at least one vascularised enthesis as predictive for diagnosing peripheral spondyloarthritis (sensitivity 77%; specificity 81%) [9]. Nevertheless, FM can exist independently in spondyloarthritis with active inflammation shown in joints and entheses of the craniocervical junction [10]. FM then has a negative impact on the response to TNF-blockade as evaluated by self-reported instruments (BASDAI etc.), rather than by levels of the C-reactive protein [11]. To examine non-inflammatory myofascial trigger points more carefully, ultrasound elastography may be an acceptable diagnostic test in the future [12].

Aspect 4: The Epidemiological View

From epidemiological data we know that FM is diagnosed more often in patients with migraine (31%), physical injury and extreme stress (15%) or cervical radiculopathy (12%) [1]. Additional data on prior major abuse or neck and whiplash injuries are not conclusive, but do not contradict a common concept of cervical dysfunction as underlying cause of FM in more than 20% of FM patients. As proposed earlier, cervical dysfunction and cervical radiculopathy, history of physical injury or extreme stress and migraine coinciding with FM should be consequently addressed in FM patients [13]. Indeed, in a FM prediction model derived from combination of American College of Rheumatology 1990 and 2011 criteria, 4 out of 8 predictors for group membership (FM or Non- FM) can be linked to a cervical syndrome (i.e. neck pain, upper back pain, shoulder pain, tender point at the lateral epicondyle) [14].

Aspect 5: Concerning Functional Imaging

It is interesting to note that resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) of the cervical spinal cord revealed unbalanced activity between the ventral and dorsal cervical spinal cord in FM [15]. For a critical appraisal of this finding, larger studies are needed, preferentially recruiting patients with the cervical and non-cervical subtype of FM.

Aspect 6: Leading to Subtype-Specific Treatment?

As a matter of fact, treatment options appear far better for cervical dysfunction than for FM. It can therefore be anticipated that physiotherapy, manual therapy, and osteopathy should be more helpful for the “cervical” type of FM patients when specifically approaching the cervical column. Indeed, promising data are available for FM patients with C1-2 dysfunction after upper cervical manipulative therapy [16], further supporting this concept of grouping FM patients into those of the cervical versus the noncervical type [17].

Craniosacral treatment is promising for all patients with chronic pain, according to a recent meta-analysis which suggested “robust short-term efficacy and comparative effectiveness of craniosacral treatment on pain intensity and functional disability” [18]. A limitation of this meta-analysis was that the studies included not only patients with cervical syndrome related features or FM (like neck pain, migraine, headache, epicondylitis, and fibromyalgia), but also those with back pain and pelvic girdle pain. Nevertheless, it rather supports than denies the concept of FM subtyping.

Taken together, treatment of FM is often not satisfactory. There is more and more evidence supporting the hypothesis of cervical and non-cervical subtypes in FM. FM-specific randomized, shamcontrolled interventional studies are needed.

To read more about this article...Open access Journal of Rheumatology & Arthritis Research

Please follow the URL to access more information about this article

To know more about our Journals...Iris Publishers

No comments:

Post a Comment