Authored by Lydia Kaoutzani*,

Introduction

Retinal detachment occurs in approximately 5 per 100,000 people per year and it is considered a medical emergency [1]. It is caused by retinal breaks that result in the separation of the neurosensory retinal from the retinal pigment epithelium [2]. Currently there are three main techniques that are used for the repair of retinal detachments including scleral buckling, pars plana vitrectomy and pneumatic retinopexy [3]. Intraocular silicone oil is one of the agents used for ocular tamponade in retinal detachment [4]. Common complications of intraocular silicone oil use include keratopathy, glaucoma and cataract [5]. Intraocular silicone oil migration is a rare complication and the focus of this paper [5].

Silicone oil migration is usually an asymptomatic entity however it has been associated with neurological symptoms such as headache, dizziness and seizures [6]. Silicone oil on CT images presents as a hyperdense lesion with predilection of non-dependent locations secondary to the lower specific gravity in relation to the cerebrospinal fluid [7]. On average specific gravity for silicone oil used in ocular surgery is 0.97 g/cm3 whereas specific gravity of CSF ranges from 1.0063 to 1.0075 g/cm3 [8,9]. On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) intraocular silicone usually presents as a hyperintense lesion on T1 sequences and has variable intensities on T2 sequences [10]. For these reasons intraocular silicone oil migration can be confused with intracerebral hemorrhage. To distinguish between intracerebral hemorrhage versus intraocular silicone oil migration one can rely on repeat imaging that will demonstrate a constant location for the intraocular silicone oil [11]. The exact mechanism for how intraocular silicone oil migrates from the eye to the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) space is still not well understood. Some theories speculate that optic nerve conditions such as glaucoma, increased intraocular pressures and trauma can contribute to this condition [12-15].

Craniopharyngiomas, a World Health Organization (WHO) grade I tumor, compromise 0.8% of all brain tumors and are usually located in the suprasellar region [16]. Craniopharyngiomas have a bimodal distribution between childhood and late adulthood, with children presenting mostly with endocrine dysfunctions and adults with visual disturbances [17]. Treatment for craniopharyngiomas involves surgical resection, radiation therapy and intracavitary therapy [17].

To our knowledge this is the first time that silicone oil migration in the intraventricular system has been observed in a patient with a craniopharyngioma. The exact mechanism of this process is not clear however the craniopharyngioma could have contributed to this process.

Case Report

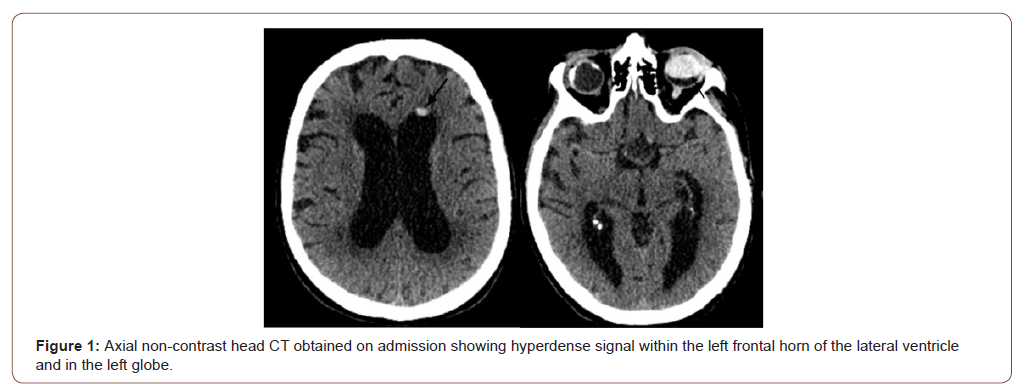

We describe a 75-year -old male who originally presented to the hospital for concerns of failure to thrive, generalized weakness and a fall three weeks prior to presentation. A non-contrast head CT scan (Figure 1) showed a hyperdensity in the left frontal horn of the lateral ventricle concerning for intracranial hemorrhage. For this reason, he was transferred to our institution for further management. The patient had an extensive past medical and surgical history. Pertinent information includes bilateral retinal detachment requiring ocular tamponade with silicone oil and subsequent left scleral buckle removal (seventeen years prior to presentation) after experiencing double vision. On presentation to the hospital he reported blindness from his left eye for the past seven years and progressive visual loss from his right eye for the last six months. His neurological exam was remarkable for left eye blindness and ability to perceive only light and broad shapes out of the right eye. Laboratory values were concerning for hyponatremia.

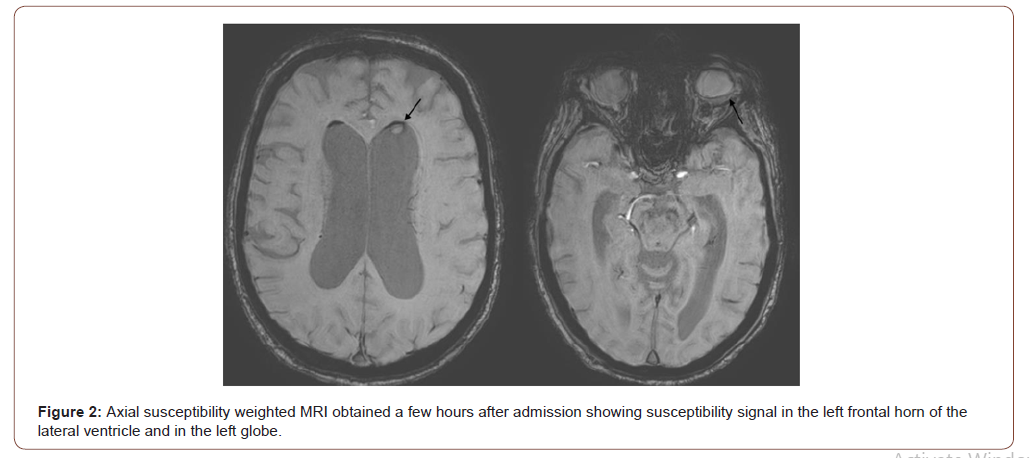

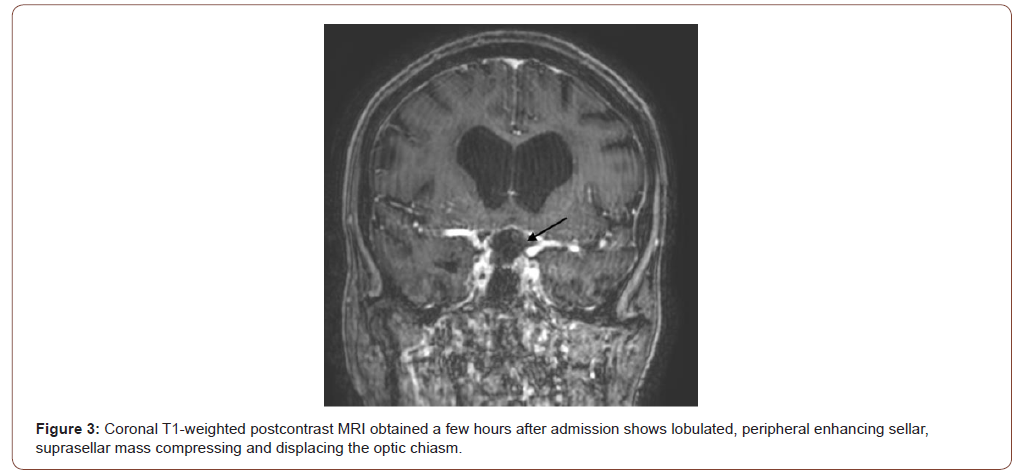

A non-contrast head CT scan showed a nodular nondependent hyperdensity at the left frontal horn of the lateral ventricle (Figure 1). Given the hyperdense substance within the left globe and the nondependent location of the hyperdensity it was concluded that this could represent silicone migration from left ocular implant (Figure 1). A few hours after admission, an MRI was performed that confirmed the above results and also found an incidental peripherally enhancing sellar/suprasellar mass (Figure 2 and 3).

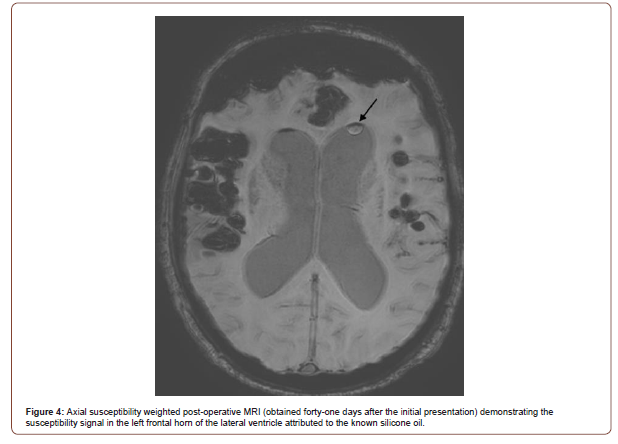

The patient was also evaluated by the ophthalmology team that reported significant decrease in his right vision without optic nerve atrophy. He was admitted to the medical service for further management. Given the progressive right vision loss and the sellar/ suprasellar mass discovered on MRI he underwent an elective transnasal transsphenoidal resection of the adenoma. On postoperative MRI, forty-one days after his initial presentation, the intraventricular silicone oil was still present in the left frontal horn of the lateral ventricle (Figure 4). The pathology results revealed a craniopharyngioma and on his postoperative visit he was found to have significant improvement of his right vision.

Discussion

In this paper we present a case of intraocular silicone oil migration that was originally misinterpreted for intracerebral hemorrhage. Even though there have been case reports of silicone oil migration in the ventricular system this remains a rare phenomenon. The patient presented in this case report was also incidentally found to have a sellar/suprasellar lesion requiring treatment secondary to progressive blindness of his right eye.

Intraocular silicone oil, has been associated with various complications, but overall it is a safe substance that has been used for the treatment of retinal detachment [18,19]. One rare complication associated with intraocular silicone oil is that it can migrate via the route of the optic nerve into the lateral ventricles of the brain. The mechanism of this complication is unclear but pathologies such as glaucoma, elevated intraocular pressure, proliferative diabetic retinopathy and trauma are possible explanations [12-15]. In a study of nineteen patients with no ocular abnormalities MRI failed to detect extraocular silicone oil in the orbit, optic nerve or cerebral ventricles at approximately four months after placement [20].

The patient in this case report had undergone removal of the scleral buckle from his left eye seventeen years ago due to diplopia. He reported blindness of the left eye for the last seven years. This could potentially explain the migration of the intraocular silicone oil in three ways. First, the intraocular silicone oil could had migrated prior to the onset of the diplopia that prompted the removal of the scleral buckle. Second, removing the scleral buckle could have caused microtrauma facilitating the remaining pieces of the silicone oil to migrate. Third, minute quantities of silicone oil could have remained in the eyeball and slowly over the years migrated through the optic nerve causing his delayed loss of vision.

In this case report, the patient was incidentally found to have a craniopharyngioma which could have contributed to the migration of the residual silicone oil implant. The exact mechanism is not clear however we speculate that there could had been minor erosions of the optic canal caused by the craniopharyngioma allowing the migration of the residual silicone oil. There have been prior reports in the literature documenting skull bone erosion secondary to craniopharyngioma [21,22].

The presence of intraocular silicone oil in the ventricles appears to be a benign finding. However, one of the biggest challenges is the ability to recognize its presence as this will save the patient from unnecessary procedures and will prompt essential medical treatment when necessary [11]. In the case of our patient the successful transnasal transsphenoidal resection of the craniopharyngioma lead to significant improvement of his right vision.

Conclusion

We present a case of silicone oil migration in the left lateral ventricle in a patient with a craniopharyngioma. To our knowledge none of the previous case reports describe a patient with intraocular silicone oil migration and a craniopharyngioma. The exact mechanism behind this disease entity remains to be determined however minor erosions of the optic canal secondary to the craniopharyngioma could had contributed in this case.

To read more about this article....Open access Journal of Neurology & Neuroscience

Please follow the URL to access more information about this article

To know more about our Journals...Iris Publishers

No comments:

Post a Comment