Authored by Jefferson Thomas A*,

Abstract

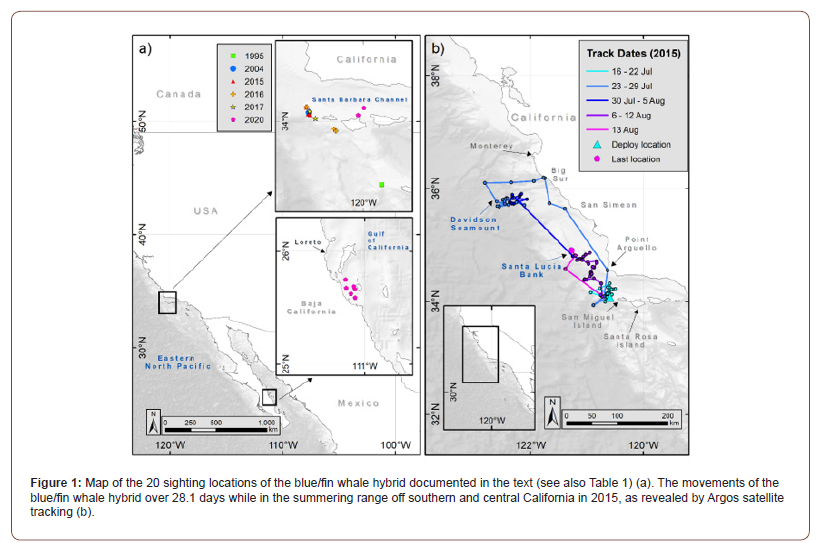

We report 20 photo-documented sightings of a blue/fin whale hybrid between 2004 and 2020, in its wintering and summering ranges in the Gulf of California, Mexico, and southern California, USA, respectively. The whale was confirmed to be a hybrid by genetic testing using a reference dataset of non-hybrid blue and fin whales. It was also tracked by satellite for 28 days in 2015, showing its feeding range extended to the Big Sur area of central California. Information is presented to assist in field identification of blue/fin whale hybrids.

Keywords: Balaenoptera musculus, Balaenoptera physalus, Cetaceans, Hybridization, California, Mexico, Migration, Tracking, Identification

Introduction

Hybridization has been documented between many pairs of marine mammal species, and intergeneric hybrids have even been reported in several cases [1]. Hybridization between blue (Balaenoptera musculus) and fin (B. physalus) whales has been suspected for over 130 years, initially based upon the appearance of “bastard whales” taken in Lapland (Norway) whaling operations in the 1880s, which seemed to have characteristics of both parent species [2,3]. In the Pacific Ocean, Doroshenko [4] reported a suspected hybrid whale caught in Soviet whaling operations in 1965. Genetic confirmation of hybridization between these two species would have to wait until 1991, when three whales caught in Icelandic whaling operations in 1983-1989 were tested and shown to have both blue and fin whale DNA [5,6]. Blue/fin whale hybrids have also been identified among whale meat samples purchased in Japan, using molecular methods [7,8].

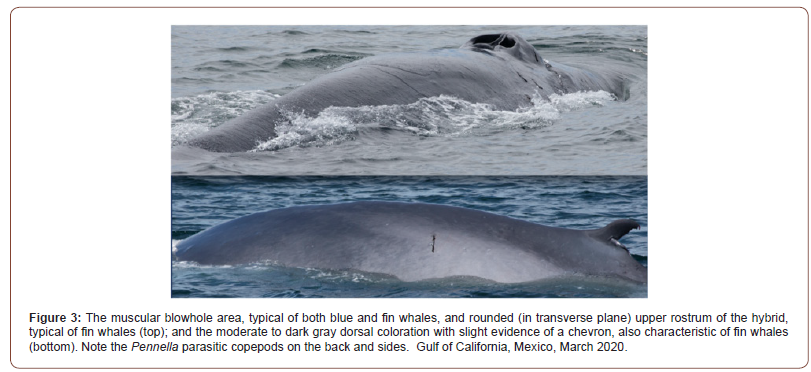

A female blue/fin hybrid caught off northwestern Spain in 1984 was reported by Berube and Aguilar [9]. This animal was examined in detail and showed features similar to what had been reported earlier, i.e., that hybrids appeared superficially more like fin whales (e.g., moderate to dark dorsal coloration, large dorsal fin), but also Citation: Jefferson Thomas A, Palacios Daniel M, Calambokidis John, Baker C. Scott, Hayslip Craig E, Jones Paul A, et al. Sightings and Satellite Tracking of a Blue/Fin Whale Hybrid in its Wintering and Summering Ranges in the Eastern North Pacific. Ad Oceanogr & Marine Biol. 2(4): 2021. AOMB.MS.ID.000545. DOI: 10.33552/AOMB.2021.02.000545. Page 2 of 9 showed some characteristics of blue whales (e.g., uniformly dark baleen, dark right lower jaw).

However, all of these records were of dead animals; little is known about how to identify hybrid whales at sea, and virtually nothing is in the literature about their behavior and ecology. The only reports of live sightings were of suspected blue/fin hybrids in popular literature [10], and accounts of hybrid whales in several unpublished abstracts and contract reports, with support from maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA and biparentally inherited nuclear markers [11-13].

Here, we report on several sightings of an individual whale, first identified by Steiger GH et al. [11] (OSU photo-ID catalog no. BpCA-052; CRC catalog nos. CRC-BM-3330/CRC-BP-114; informally referred to as “Flue”), identified as a blue/fin whale hybrid from molecular markers, and confirmed as the same individual from photographic and genetic evidence. We give details on its sighting history, movements, behavior, and ecology in its wintering and summering ranges, as well as information that will help identify such hybrids in future sightings.

Summering Range Sightings

Excluding a 1995 record that is somewhat uncertain, the hybrid whale has been visually identified 13 times in southern California between September 2004 and August 2020 (Figure 1, Table 1). The first confirmed identification of this whale was on 22 September 2004, during a Cascadia Research Collective photo-identification survey. The animal had a highly distinctive dorsal fin, with damage that could have been caused by entanglement with fishing gear or from being struck by a vessel (Figure 2). It was later sighted and tagged on its right side on 16 July 2015 west of San Miguel Island and resighted in the same area on three more days shortly after tagging (18, 20, and 21 July 2015) (Table 1). There was slight swelling around the tag site on 18 July, two days after tagging. Photos from the left side only were obtained on 20 and 21 July 2015 and an assessment of the tag site on those days was not possible. In 2017 it was again encountered and re-identified during additional tagging work west of San Miguel Island [13] on two different days (13 and 17 July; 738 and 743 days after tagging, respectively; Table 1). During these re-sightings, the animal appeared somewhat skinny, with a slight depression along its flank beneath the sagittal midline, an appearance that is not uncommon in blue whales arriving in southern California waters from the wintering range. The tag was no longer attached and there was no visible swelling at the tag site. The wound had a bit of lighter color where the tag was placed, but otherwise it could not be distinguished from other small wounds caused by ectoparasites and cookie-cutter shark ((Isistius sp.) bites. The most recent sightings were made by several whalewatching vessels in the California Channel Islands area in July and August 2020 (Table 1).

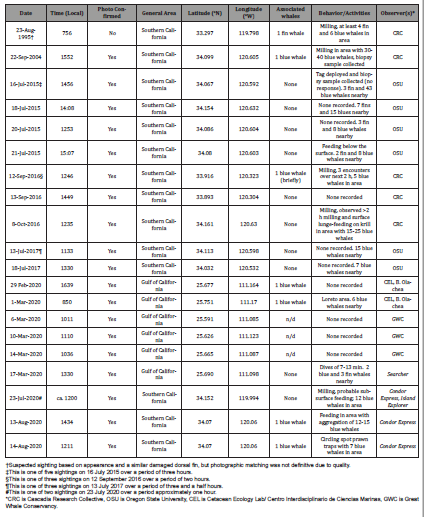

Table 1:Sighting history of a male blue-fin whale hybrid in the eastern North Pacific.

The hybrid had a mild infestation of the ectoparasitic copepod Pennella balaenopterae on its dorsum when sighted in 2015 (Figure 3), with fewer seen when it was re-sighted in 2017. There were also a large number of scars, holes, and nodules seen in the skin (Figure 2), which were probably related to these parasites or other skin conditions. Pennella infestations were commonly observed on both fin and blue whales during the four years (2014-2017) of the tagging project [13], with fin whales showing higher numbers. An exhaustive examination of photographs collected by Oregon State University during similar tagging work from 2004 to 2008 indicated that Pennella infestations were rare on fin whales and very rare on blue whales off California in earlier years.

Wintering Range Sightings

The whale was sighted six times near Loreto, in the southern Gulf of California, Mexico, between 29 February and 17 March 2020 (Figure 1, Table 1). On 17 March, detailed observations were made during a natural history tourism cruise aboard the Searcher in the Gulf of California, over an extended period in good sighting conditions (Beaufort Sea states 1-2). The whale was observed in the area between 2.8 km WSW and 3.7 km NW of the northwest tip of Isla Monserrat (Figure 1a). The general behavior of the whale involved dives of 7 to 13 minutes in duration, fluking up on about half of the dives. Twice it logged on the surface. Several times, it swam counterclockwise around the vessel. At other times it surfaced in a manner that allowed for a good view of the right side of the rostrum through the water surface. No indication of the asymmetrical white lower jaw diagnostic to fin whales [14] was seen by observers on several different decks of the Searcher. The observers agreed that the whale was likely a hybrid. Three fin whales and two blue whales were seen shortly after this time, providing a nearly concurrent observation with which to compare the animals, and white lower right jaws were clearly visible on the fin whales.

Summering Range Tracking

During tagging operations on blue and fin whales in southern California [12,13], the hybrid was tagged on 16 July 2015, 13 km west of San Miguel Island, and was tracked for 28.1 days and 1,445 km until the tag stopped transmitting on 13 August 2015 (Figure 1b). Given its dark coloration and prominent dorsal fin, the animal was initially identified in the field as a fin whale. It was instrumented with a fully implantable Wildlife Computers SPOT5 (Smart Positioning or Temperature Argos-transmitting tag, version 5), which was placed on the right side of the animal, 2.5 m forward of the dorsal fin. The whale showed no behavioral response to tagging or biopsy darting. A total of 95 Argos locations were recorded. The first six days of the whale’s tracking period were spent along the continental shelf edge in the same general area in which it was tagged, before it moved inshore to Point Arguello (Figure 1b). The hybrid then undertook a three-day trip north along the coast as far as Big Sur, California, then west and south toward Davidson Seamount. The next five days were spent between the shelf edge and Davidson Seamount, followed by a four-day gap in transmissions, after which the whale was located 154 km south at Santa Lucia Bank. The final eight days of the whale’s tracking period were spent between Santa Lucia Bank and the tagging location west of San Miguel Island (Figure 1b). This type of circuitous movement behavior while in the summering range was recently described for males of both blue and fin whales [15].

The area west of San Miguel Island is an important foraging area for baleen whales, with the southward wind-driven upwelling from Point Conception, shelf breaks, island slopes, and nearby seamounts supporting dense aggregations of euphausiids, as a result of increased turbulence, mixing, and surface nutrients [15- 17]. During its tracking period, the whale occurred in waters that had a mean depth of 1,256 ± s.d. 1,198m, a mean distance of 30.3 ± s.d. 26.8km from the shelf break, and a mean distance of 49.3 ± s.d. 21.1km to shore. Mean satellite-measured sea surface temperature was 18.1 ± s. d. 0.6 °C and mean chlorophyll-a concentration was 0.71 ± s.d. 0.47 mg m-3. The tag stopped functioning before the animal migrated to its wintering range.

Genetic Identification

A remote biopsy sample was obtained from this individual at the same time it was satellite tagged on 16 July 2015 (Table 1). The whale was identified as a male by multiplex polymerase chain reaction using the primers Y53-3C and Y53-3D to amplify a 224-bp region on the Y chromosome [18,19]. Species identity was verified by submitting mtDNA sequences to the web-based program DNAsurveillance [20] and by Basic Local Alignment Search Tool search of GenBank®. Because the initial identification of the species as a blue whale from mtDNA did not agree with the field observations as a fin whale, a Bayesian clustering was conducted to assess the potential for hybrid ancestry [21]. Using a reference dataset of multi-locus genotypes (n = 17 microsatellite loci) from North Pacific blue whales (n = 75) and fin whales (n = 75), we confirmed that the inferred ancestry of each reference sample was consistent with its presumed species origin, either >99% blue or >99% fin. Only the putative hybrid showed evidence of hybrid admixture, with an inferred ancestry of 68.5% fin whale and 31.5% blue whale. Further, given the maternal inheritance of mtDNA and the biparental inheritance of the microsatellite loci, the results indicated that the parents of the hybrid were a blue whale mother and fin whale father. Finally, the “DNA profile” for the hybrid individual, consisting of the 17 microsatellite genotypes, sex, and mtDNA control region sequence, was compared to other profiles in the reference dataset. This comparison revealed a match with a previously reported hybrid individual, first sampled off California by Cascadia Research Collective on 22 September 2004 (Table 1) [11].

Field Identification of Hybrid Whales

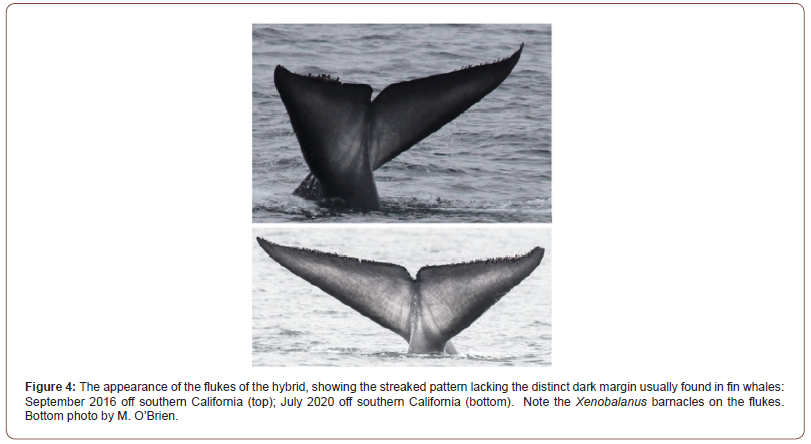

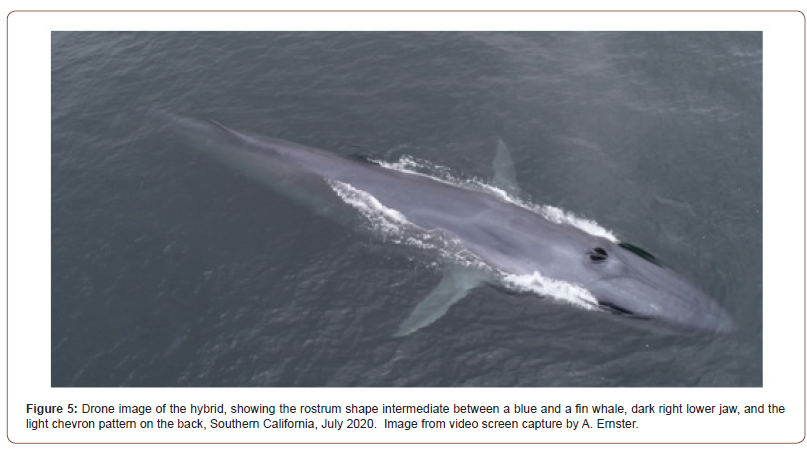

The detailed sightings described above have provided us the opportunity to report information that can be used in future sightings of suspected hybrid blue/fin whales. From literature reports and our detailed observations, blue whale/fin whale hybrids seen at sea appear superficially very similar to fin whales (i.e., moderate to dark gray dorsal coloration with a light chevron, mostly dark baleen plates; relatively large (compared to a typical blue whale) falcate dorsal fin with a shallow angle to the leading edge, more acute rostrum (with rounded upper surface), but show several coloration and morphological characteristics that are associated with blue whales (i.e., dark gray lower jaw on both sides, dark or bluish ventral grooves, indistinct mottling, streaked underside of flukes lacking a distinct dark margin, and deepened tail stock (Figure 2-5). Hybrid whales can have either species as the mother [5,22] and may at times associate, travel, and feed with both fin and blue whales [10,13] (Table 1). While not necessarily occurring on every long dive, fluking up behavior appears to be common in hybrid blue/fin whales (at least based on this whale), while being rare in fin whales [14]. Albeit not diagnostic, two other features resemble a blue whale: the overall size and girth of the whale, and a slight slump between spine and flanks [14]. Length estimates for the whale ranged between 18-21 m, within the range of overlap of both parent species, though some observers suggested that it appeared closer to the typical size of adult blue whales (23- 27 m) [14].

Conclusions

The hybrid whale appears to prefer associating with blue whales. It has been seen among loose aggregations (which may cover several tens of square kilometers) of both blue and fin whales in both the summering and wintering ranges. However, the majority of whales in the area have generally been blue whales, and in all cases (except one) in which the hybrid surfaced with another whale, those whales were blue whales.

There are two putative populations of fin whales in the eastern North Pacific Ocean, one off the west coast of North America and one in the Gulf of California. Both populations have distinct migration patterns, with west coast fin whales remaining in southern California during the winter [23,24,25] and Gulf of California fin whales remaining within the Gulf [26]. In contrast, blue whales migrate seasonally, spending summer months feeding off the west coast of North America and breeding/calving in the Gulf of California and the Costa Rica Dome, an oceanographic feature in the eastern tropical Pacific [27]. The hybrid has been seen among both blue and fin whales in both of its seasonal ranges. One question is to which of the two fin whale populations did the hybrid’s father belong? The 2020 sightings in the Gulf of California suggest natal philopatry, which is maternally transmitted [28], and migratory behavior more like its blue whale mother. Another intriguing question is whether blue/fin whale hybrids might be the source of the mysterious 52-Hz whale calls periodically recorded in the North Pacific Ocean [29].

Blue/fin hybrids may not be rare and appear to be present in much of the overlapping ranges of the two parent species. These two species are related (though not particularly closely [30]), and have similarities in their morphology, ecology, and behavior, characteristics that are known to be associated with pairs of species that frequently hybridize [31]. Though some fin whales are considered to be resident in the Gulf of California [26] there is some potential evidence of connectivity with southern California [24,32,33]. Taken together, the 19 confirmed sightings of this hybrid individual that we report here indicate movements from the coast of California in summer/autumn to the lower Gulf of California, Mexico, in spring (a distance covered of at least 1,500 km). This is suggestive that hybrids may follow a regular migration pattern more typical of blue whales [17,27]. However, we do not know if this whale has mated (note that fetuses found in female blue/fin whale hybrids show they can be fertile [9,22]). How often such hybrids occur and how their presence and potential mating would affect the gene pool of the two parent species is not well understood at this point. Pampoulie C, et al. [34] suggested that blue/fin hybridization is typically unidirectional (male fin X female blue), and that the frequency of hybrids might be underestimated. It is our hope that the observations presented here will encourage others to report and publish sightings of suspected or confirmed hybrid whales in the future.

To read more about this article...Open access Journal of Oceanography & Marine Biology

Please follow the URL to access more information about this article

To know more about our Journals...Iris Publishers

To know about Open Access Publishers

No comments:

Post a Comment