Authored by Mitzi S Brammer*,

Abstract

The purpose of this review is to capture the scope of literature regarding resilience related to those faculty teaching in higher education. More specifically, this researcher is interested in those strategies and interventions that can be utilized to foster resilience among higher education faculty. In its infancy, research and intervention addressing this topic occurred at the K-12 level of education and later moved into baccalaureate programs of study for the most part. From an empirical standpoint, little is still known about resilience of faculty in higher education. Using Carl Rogers’ [1] self theory as a theoretical framework, the author investigates the literature in terms of the connection (as well as disconnection) between one’s selfimage and one’s ideal image. Through this theoretical lens, correlates of resilience as well as ways to foster resilience in instructors and professors in higher education are discussed. A deeper understanding of these factors will drive future research in terms of the development and evaluation of appropriate interventions to address faculty resilience in higher education with an intended emphasis on faculty who teach in health sciences.

Keywords:Resilience; Growth mindset; Higher education; Faculty

Introduction

The constructs of resilience and growth mindset in education have been studied in different contexts for over twenty years. The primary subject of resilience in higher education has also been explored; although, it does not have the breadth nor depth of research as K-12 educational literature. The literature addressing resilience and growth mindset in higher education is targeted primarily at undergraduate students’ experiences. However, specific post-baccalaureate programs of study have had some research conducted in terms of student resilience, including, but not limited to, medical and allied health fields [2]. In her research on the topic of growth mindset and resilience, Dweck [3] discovered that students with a growth mindset display a more resilient pattern while those holding a fixed mindset are more likely to withdraw and become helpless when facing failure. According to Vermote, Aelterman, Beyers, Aper, Buysschaert, and Vansteenkiste [4], the implication for higher education faculty is that this pattern may also generalize to teachers’ [professors’/instructors’] mindsets. There is a paucity of work on this topic currently.

From an instructional standpoint, study of the resilience of educators again has focused on teachers working with students in grades K-12. As previously noted, research on resilience of professors and instructors in higher education is limited. Interestingly, burnout, which can be the effect of a lack of resilience, has had current attention in research. Burnout is not a recent term, though. First defined in the 1970s, burnout has been described as feeling exhausted, out of energy, and feeling unable to make it to the end. Ercan Demirel and Erdirençelebi [5] add that it can be characterized as a continuous and acute feeling of tiredness and unwillingness, as well. Toxic stress can bring about burnout in academia. The current climate in higher education has increased the sense of insecurity and frustration for many [6]. Seventy-three percent of all faculty positions are off the tenure track, according to a new analysis of federal data by the American Association of University Professors [7]. Workload has contributed to the stress levels of higher education faculty, as well. According to Aguilar [8] and Sproles [9], many faculty members find administrative work to be more stressful and less fulfilling than teaching. A leadership role that initially seems like an honor, especially to a junior faculty member, can quickly become a burden, resulting in toxic stress. Aguilar [10] notes that decreased productivity is an early indicator of toxic stress, eventually escalating to the more serious symptoms, including burnout, mentioned earlier. Service pressures are especially strong for men of color and all women, who report greater service loads along with higher expectations for availability [11]. Simultaneously, life can become more demanding as higher education faculty make outreach connections in the communities, their parents age, and, for those with children, this can be a significant, albeit negative, tipping point. All these experiences create an excess of emotion that can become difficult to manage [12]. Moreover, the current outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic has brought its own unique stressors. Colleges and universities are not only focused on the resilience of their students, but also the resilience of their faculty and staff.

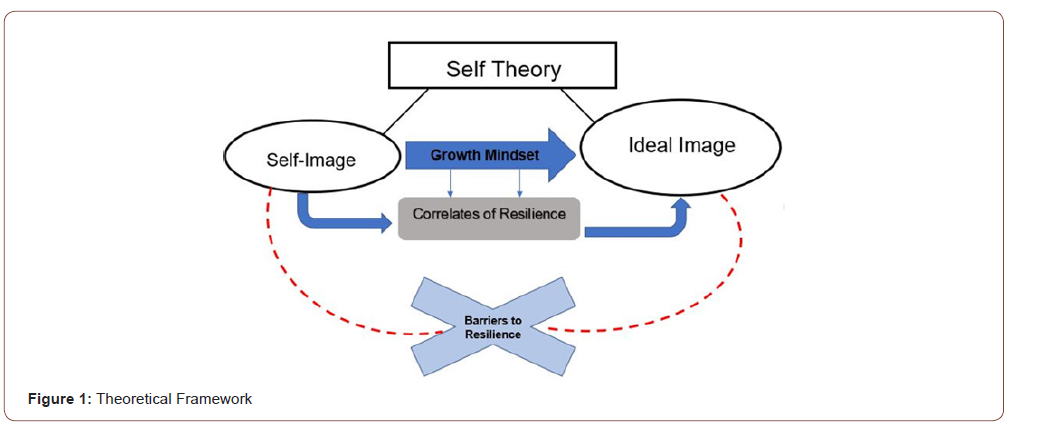

This literature review explains resilience and growth mindset as it relates to higher education instruction. The review of literature is grounded in Carl Rogers’ self-theory. He believed that an individual’s self-concept is not only a useful explanatory construct, but a crucial one to explain behavior [13,14]. Two important pieces of Rogers’ theory are reflected in the self-image and the ideal self. Individuals mature and grow forming perceptions about themselves unconsciously. Social circumstances impact the perceptions that are made. The ideal self-shows the ideal view perceived by an individual, whereas the self-image is the reality that an individual perceives [15]. In some cases, there is a disconnect between the self-image and the ideal self. This disconnect can cause issues with establishing a growth mindset and thus, can negatively impact resilience. Figure 1 shows how this theoretical framework will be used to discuss the current state of faculty resilience in higher education.

The first section of the literature review describes broad understandings of resilience and growth mindset. The next section delves more deeply into growth mindset, contrasting it with a fixed mindset. Those behaviors and attitudes that contribute to a fixed mindset often serve as barriers to resilience. The third section discusses what researchers have determined as the correlates of resilience. The final section explains what researchers and scientists have found to be effective ways for individuals (including higher education faculty and staff) to establish a growth mindset and foster greater resilience.

Broad understandings of resilience

In her work as a psychology professor, Angela Duckworth [16] sought out how to measure resilience. In doing so, she helped to further define what resilience is. She utilized a different term, however, calling a combination of passion and perseverance “grit” (p. 8). Resilience has also been defined by Southwick, et al [17] as not just functioning well considering less than positive circumstances. Zolli and Healy [18] stress that in his definition, Bonanno was not describing resilience as a lack of feeling or absence of sadness. He used the term “resilient” to identify people capable of functioning with a sense of core purpose, meaning, and forward momentum in the face of challenges. Resilience is also the individual’s ability to make sense of the moral aspects of their life and determining what matters most at a given time [19]. The phrase “at a given time” is important in that researchers have also explained that a person’s resilience is not static, nor is it finite. According to Clarke and Nicholson [20], “Resilience appears to be an aspect of personality so powerfully influenced by experience that the jelly never quite sets; it’s probably never too late to increase one’s resilience” (p. 18).

An extensive study conducted by Gallup scientists explained resilience in terms of five universal elements of wellbeing: career, social, financial, physical, and community. They are universal in that they are common among the collective. These scientists define resilience as a personal characteristic that allows a person to persist when there is an imbalance in any of the five elements of well-being, including in the workplace [21]. Like the aforementioned authors, Aguilar [22], Clarke and Nicholson [23] and Duckworth [24] hold that resilience [grit] is comprised of multiple facets, including who one is (genetics, values, personality); what one does (habits); how one feels (emotions and disposition) and where one is (context). Further defined, context has to do with a person’s circumstances and situation, the sociopolitical, cultural, and economic context and the stage of life and phase of career in which a person finds himself or herself [25].

Related to resilience and grit is the notion of quality of work life (QoWL). It is currently being assessed in a number of professional fields including healthcare. This idea is defined by how well members of a work organization are able to satisfy important personal needs through their experiences in the workplace [26]. These authors further explain that quality of work life involves a part of life and helps to balance personal life of an employee with his or her job. It is concerned with reducing stress levels and increasing job satisfaction to the mutual benefit of the individual and the organization, thus increasing individual and organizational resilience.

Growth mind set vs. fixed mindset

A growth mindset and a fixed mindset are attitudinal as well as behavioral in nature [27]. According to Dweck [28], a fixed mindset involves perceived “static givens” of character, intelligence, and creativity that cannot be altered. On the other hand, individuals who possess a growth mindset thrive when challenged and see failure not as evidence of unintelligence but as a catalyst for growth and for stretching their existing abilities. It is a myth that an individual can possess either a growth mindset or a fixed mindset. Most likely, individuals exhibit characteristics of both mindsets. According to Brock and Hundley [29], growth and fixed mindsets are dichotomous designs that exist on a continuum. While we strive to become a fully realized exemplar of growth mindset, these authors contend that we likely will always be on a journey toward the ideal. Research shows that when one can get students to buy into the idea that the brain, like a muscle, has the capacity to strengthen and grow, the result is better motivation, stronger desire to succeed, and higher achievement in courses [30].

The language that instructors and professors use with students can impact whether the student will maintain a fixed mindset or a growth mindset [31]. For example, statements such as “You’re a natural in biophysics” undermines a growth mindset whereas “You’re a learner! I love that.” promotes a growth mindset. Back [32] and Duckworth [33] explain how powerful the word “yet” can be when talking about students’ skills in a particular academic/ subject area. When a professor gives feedback that includes, “This is difficult. Don’t feel bad if you can’t do it,” the stage is set for a fixed mindset. This is strikingly different than if the same professor would say, “This is hard. Don’t feel bad if you can’t do it yet.” Including that small, but powerful, word relays hope and helps to cultivate a growth mindset.

A growth-mindset professor approaches academic situations quite the opposite than a fixed-mindset professor. A fixed-mindset professor believes a particular student is incapable of doing well in their class. Moreover, they are of the belief that if the students hate their course, it is the students’ loss and there is nothing they can do to change that. For the growth-mindset professor, college-level meetings and professional development are perceived as a way to get new ideas rather than a waste of time [34]. Growth-mindset professors reflect on their instruction by asking, “How can I present my lectures so that my students understand the content better?” They ask, “What ARE my students interested in and can I tie that to my content?”

Correlates of resilience

Zolli and Healy [35] believe that all the correlates of resilience are entrenched in one’s beliefs and in experiences. Aspiration is one correlate of resilience. It is entirely possible to aim high, believing one will do well, while being at peace with the results. This is highly apparent when junior faculty apply for tenure or promotion. If one has tried their best, it is alright to fail. But at the same time, it is important to not take what happens too personally [36]. Some faculty might argue that Hanson’s [37] statements are easier said than done. When it comes to promotion and tenure, failure does not seem to be an option. Emotional intelligence, or EQ, is another correlate of resilience [38]. Emotional intelligence is defined by Schneider, Lyons, and Khazon [39] as “one’s ability to perceive, integrate, understand, and manage emotions” (p. 909). Clarke and Nicholson [40] and Tugade and Frederickson [41] believe that individuals who have high emotional intelligence are effectively able to use positive emotions to their advantage. Clarke and Nicholson’s [42] and Zolli and Healy’s [43] research highlighted optimism as a major indicator of resilience. According to these authors, “optimists believe that things are getting better all the time, and not necessarily just for themselves, but for others close to them and for society in general. Optimists are therefore likely to view change positively, and to be more confident about what the future holds--and that they will be able to cope with it” [44]. In his work, Seligman [45] discussed the relationship between optimism and resilience. People who are optimistic can see negative events in a logical context, realizing that factors that influence the negative event are out of their control.

One’s resilience is rooted in the groups and communities in which they live and work, according to Clarke and Nicholson [46] and Zolli and Healy [47]. In order to cope with and bounce back from tough times, one needs to involve others. Resilience requires an individual to strike a balance between attempting challenging tasks alone and relying on other people, as well as between healthy competition and cooperation [48]. From a pedagogical perspective, instructors in a fixed mindset will say that they do not have much to learn from students or colleagues. Instructors possessing a growth mindset, on the other hand, trust other people to be their greatest allies in helping them to become more successful at work and life. The growth mindset instructor values other people because other people can teach them a lot [49]. In his work on resilience, Hanson [50] lists several additional correlates of resilience. These include confidence, courage, learning, mindfulness, and motivation. Two of these correlates, mindfulness and learning, will also be discussed in the next section in terms of effective ways to establish a growth mindset to foster resilience.

Fostering resilience

Mindfulness practices have been shown to be effective in fostering resilience [51,52]. Hanson [53] notes that an individual’s brain is shaped by their experiences, which are shaped by what they attend to. With mindfulness, one can focus their attention on “experiences of psychological resources such as compassion and gratitude and hardwire them into the nervous system” (p. 48). When a person engages in mindfulness practices, they are able to take more intentional control over their emotions, decrease what is painful and harmful, and increase what is enjoyable and beneficial [54, 55]. Becoming a learner is another way to foster resilience. Clarke and Nicholson [56] believe that when one takes positive learning from situations that have gone wrong, this not only boosts self-esteem but also one’s self-efficacy-the belief in oneself and one’s ability to succeed. Hanson [57] cautions against confusing learning with positive thinking. Rather, it is about realistic thinking, or seeing the whole assortment of reality with its problems and pains as well as its many reassuring, pleasurable, and useful parts.

In their research, Chen, Powers, Katragadda, Cohen, and Dweck [58] introduced the notion of a strategic mindset in terms of fostering resilience. They differentiated a strategic mindset from general self-efficacy, self-control, grit, and growth mindsets and showed that it explained unique variance in people’s use of metacognitive strategies. “This mindset involves asking oneself strategy-eliciting questions, such as ‘What can I do to help myself?’, ‘How else can I do this?’, or ‘Is there a way to do this even better?’, in the face of challenges or insufficient progress”. Their findings suggest that being strategic entails more than just having specific metacognitive skills-it appears to also entail a focus on seeking and utilizing them.

Unfortunately, effects of the current coronavirus global pandemic are felt in the college and university classroom and not just by the students. Loneliness caused from working from home results in feelings of isolation [59], impacting resilience. Sharma [60] recommends starting an online community with colleagues in one’s field of study. Doing so provides an opportunity to rethink how we interact with one another in ways that will benefit the scientific community in the long term. Gray [61] uses the term “quarantine fatigue” to describe feelings of tension, exhaustion, irritability, or anxiety from balancing work and home responsibilities, worrying about finances, and maintaining longer than usual work schedules. The author recommends finding ways to adapt to current circumstances by creating routines and schedules. He also recommends making personal time for oneself while also connecting with friends and family. Additionally, try to allow time for physical exercise and maintaining a healthy diet. Students who have used these techniques during quarantine derived benefit [62].

Conclusion

This literature review has presented general understandings of resilience and growth mindset. Additionally, the author has explored what the research says about a growth mindset as it relates to a fixed mindset, recognizing that certain behaviors and attitudes contributing to a fixed mindset often serve as barriers to resilience. Correlates of resilience were also presented as part of this review. Finally, those strategies that researchers and scientists have found to be effective for individuals (including higher education faculty and staff) to establish a growth mindset and foster greater resilience were shared. A deeper understanding of these ideas will help strengthen resilience-thinking abilities. This, in turn, can bring us to a different way of being in the world, and to a deeper engagement with it [63].

To read more about this article..Open access Journal of Journal of Complementary & Alternative Medicine

To know about Open Access Publishers

No comments:

Post a Comment