Authored by Amanda Thomas*,

Abstract

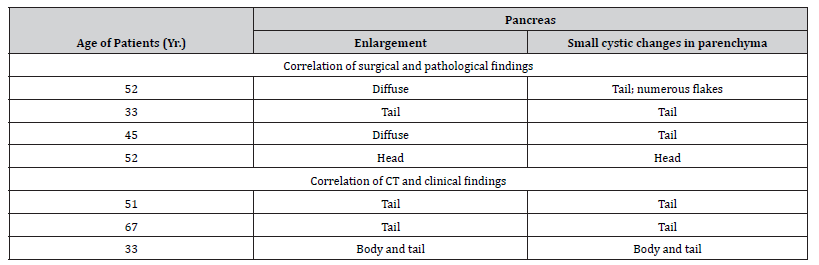

Objectives: To present a description of Critical Care Physiotherapy staffing during the COVID-19 pandemic in a London Hospital, including calculations of occupied bed to physiotherapy staff ratios, and staff productivity.

Methods: Physiotherapy intervention data was collected between 2nd November 2020 - 28th February 2021, coinciding with the second COVID-19 pandemic surge. Staffing numbers were collected throughout this period, allowing calculation of staff to occupied bed ratios and staff productivity.

Results: Staff productivity ranged from 44% to 130% and physiotherapist to occupied bed ratio ranged from 1:9 to 1:11.

Conclusions: Staffing ratios are common metrics within nurse reporting but are novel within the allied health professions. It is unclear whether changes in Physiotherapy staffing ratios impacts time to activity milestones in our COVID-19 critical care population. The practice of redeploying staff to improve staffing ratios is a complex intervention. Training and service familiarization needs to be considered for redeployment to have a positive impact on staff productivity.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in unprecedented demand for all critical care staff including physiotherapists. Estimating the Physiotherapy labour requirement for the number of patients admitted to critical care during the pandemic was problematic. With the rapid increase in demand for critical care beds this presented a challenge to develop safe staffing guidelines in an unfamiliar environment [1]. Although guidelines for Intensive Care Services in the United Kingdom exist (GPICS, 2019), what constitutes appropriate staffing during a respiratory pandemic is less clear. In addition, historical methodologies used in workforce planning remain rudimentary and poorly substantiated [2]. For example, ratio-based methodologies compare staff to an activity variable (beds, bed-days, or activities) which may be established at a service level or externally referenced from professional standards [3,4]. These methods rarely consider the percentage of time devoted to direct clinical care compared to supporting professional activities [5] and descriptions of ratio calculations which accommodate 7 day or extended hours working are rare. In addition, ratio methodology is rarely able to establish links between staffing and a desired health outcome [6]. Importantly, evidence for labour efficacy or productivity remains unreported in the ratio-based taxonomy.

The second COVID-19 pandemic at the Royal London Hospital (RLH) provided an opportunity to explore Critical Care Physiotherapy incidence and outcome in relation to changing patient volume, staffing configuration and service provision over a four (4) month period. Since workforce increased incrementally with patient volume and occupied critical care beds over the time period, we aim to: -

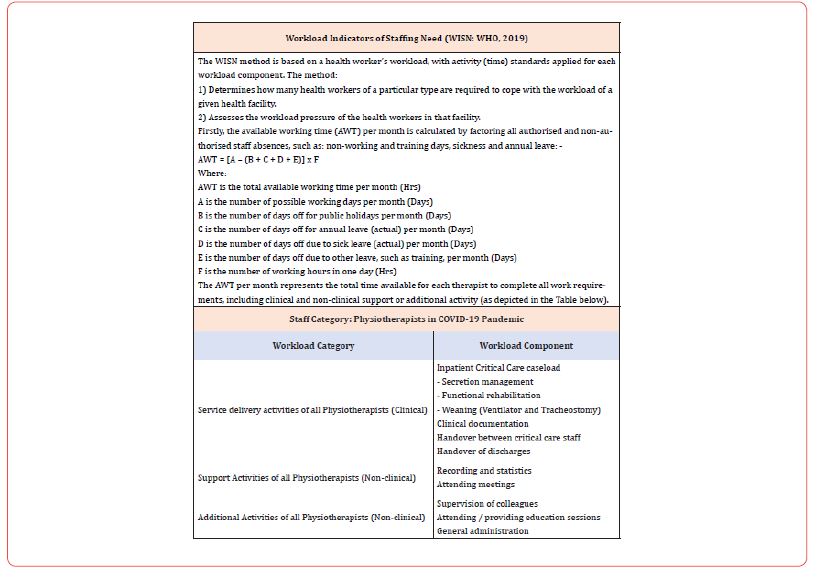

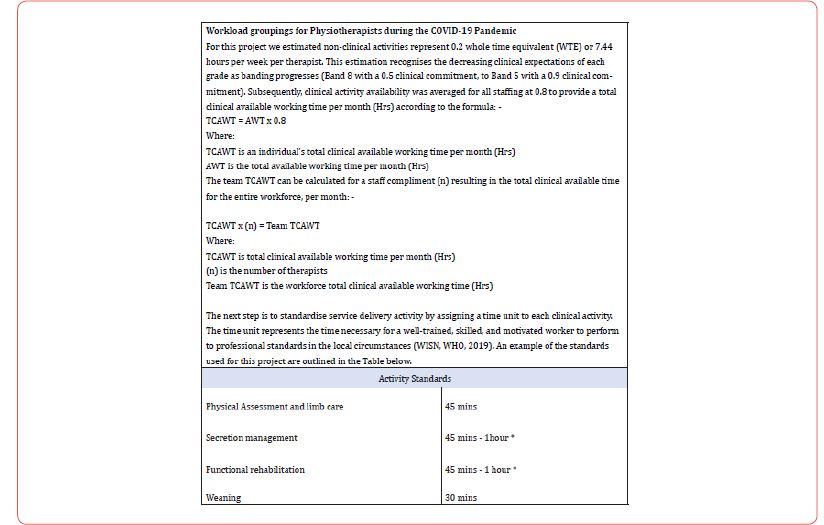

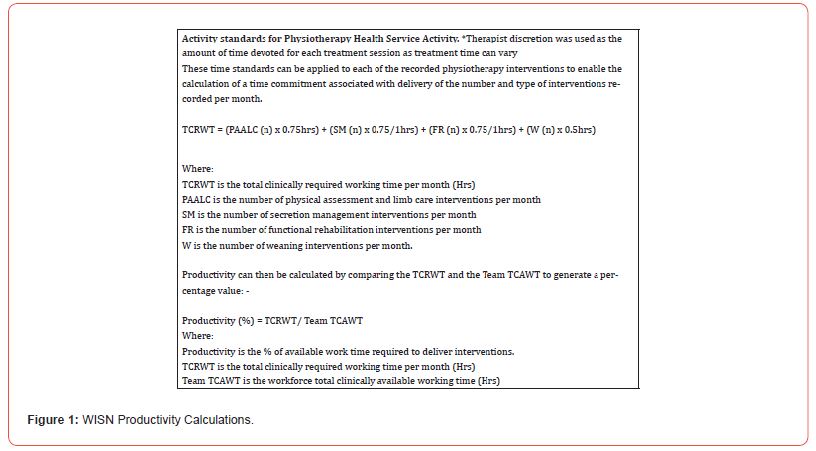

a) Present a description of our Critical Care Physiotherapy service, including the method of calculating our therapist to occupied bed ratios and a methodology for establishing staff productivity adapted from the World Health Organization (WHO, 2019) Workload Indicators of Staffing Need (WISN) (see full details in Figure 1).

b) Describe the volume and nature of Physiotherapy delivered each month by the Physiotherapy workforce with reference to occupied bed ratio.

We hope that illustrating the granular detail of workforce metrics and productivity during the COVID-19 pandemic supports recognition of the complexity associated with Physiotherapy workforce planning and contributes to on-going predictive modelling and debate.

Methods

This was a single centre observational project in the Royal London Hospital (RLH), London, United Kingdom. In a companion paper we present details of the environment, data collection and data management methods.

Physiotherapy Staffing: The increase in COVID-19 admissions and expanded critical care bed numbers elicited a graded therapy staffing response, reaching a peak of 26 Physiotherapists in January 2021. Core services were delivered between 8am and 6pm Monday to Friday, with a prioritized physiotherapy weekend service, and overnight on-call from 6pm to 8am. Redeployed therapists were provided with local induction and clinical skills training. All therapy staff were fit tested and provided with Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) training.

Staffing Ratios: Physiotherapist to occupied patient bed ratios were calculated by using the number of beds occupied by COVID-19 patients and dividing this by the number of Physiotherapists dedicated to providing the COVID-19 Physiotherapy service. Due to differences in the weekday / weekend prioritized service, we calculated a ratio for weekdays and for weekends separately, then combined these ratios to calculate a monthly average.

Productivity Calculation: A modified version of the World Health Organizations - Workload Indicators of Staffing Need (WISN: WHO, 2019) was used to calculate productivity. This tool, developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) provides a systematic process to guide staffing decisions optimizing human resource management. The application of the WISN model allowed calculation of productivity, staffing levels and intervention data. For a full description of the WISN calculations please refer to Figure 1. Ethical Considerations: Ethical approval and patient consent were not required as the project was registered as a service evaluation by the clinical effectiveness unit at The Royal London Hospital. There was no deviation from usual care for any patient, the project was observational.

Results

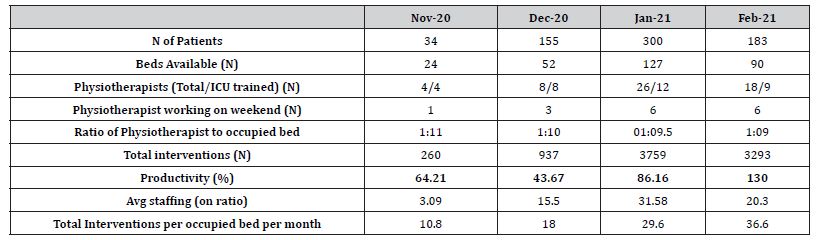

Patient volume and critical care bed capacity increased over the first 3 months peaking in Jan 2021 when 300 critical care patients were cared for in 127 critical care beds (Table 1). In the last month (Feb 2021), these numbers reduced to 183 patients, cared for in 90 critical care beds. The Physiotherapist to occupied bed ratio changed monthly from 1 Physiotherapist for every 11 beds in the first month (Nov 2020), to 1 Physiotherapist for every 9 beds in the fourth month (Feb 2021). Table 1 demonstrates how increased critical care beds and Physiotherapy availability elicited increases in the number of interventions delivered from 260 interventions in Nov 2020 to 3,759 interventions in Jan 2021. These numbers equate to 10.8 interventions per month per bed in Nov 2020, 18 interventions in Dec 2020, 29.6 interventions in Jan 2021 and 36.6 interventions in Feb 2021. Productivity was calculated as 64% in Nov 2020, 44% in Dec 2020, 86% in Jan 2021 and 130% in Feb 2021.

Table 1:Patient Volume, Workforce Metrics, Total Interventions and Productivity

Discussion

Ratio-based staffing is well established for professions such as nursing and medicine [7,8] but less so for the allied professions. Disclosure of our therapist to occupied bed ratio is novel with respect to other critical care physiotherapy literature where staffing ratios are rarely reported [9]. Over the 4-month period, our therapist to critical care occupied bed ratio’s varied between 1: 9 and 1: 11. McWilliams et al (2021) report one physiotherapist for every 10 patients in a study of rehabilitation in COVID-19 patients requiring invasive ventilation. In contrast, Black et al, 2021 [10] described the need for 1 therapist for every 5 beds occupied by intubated and ventilated patients to accommodate the large volume of secretion clearance interventions they observed, and the need for more than one physiotherapist to deliver these interventions in their COVID-19 cohort. In a previous study [9], exploring Physiotherapy in a COVID-19 positive and negative cohort we reported a Physiotherapist to bed ratio of 1:5, a value which aligned with Black et al. 2021 [10] and approximated the Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine in the United Kingdom (GPICS, 2019) and the European Intensive Care Society [11] recommendations.

Given the variance in reported therapist to patient, and therapist to occupied critical care bed ratios described above, we present a translation of our staffing ratios into productivity metrics as a tool to evaluate service provision. Productivity can be defined as the rate of work per unit, where the work represents interventions delivered (converted to a time unit) and the unit represents the available therapy staff hours (accounting for non-clinical activity). Staffing enhancement (as occurred during the pandemic) increases available working hours, but this enhancement did not automatically improve work productivity in the initial period. Our low derived productivity scores in the first 2 months may suggest a period of “over- staffing” but more likely this period was associated with increased non-clinical activity allocation. Tasks such as training and up-skilling, strategic planning, developing resources and role allocation were occurring alongside clinical delegation and supervising interventions. These non-clinical tasks were necessary to ensure staff met minimum standards of critical care clinical practice [12] and had an appreciation of the evidence base underlying treatment recommendations in this environment [13- 17] and the recommended staff required to complete interventions [18].

It is noteworthy that during the first two months of data collection, caseload commitments of Physiotherapy staff were divided between a COVID-19 negative cohort in one clinical area (the Adult Critical Care Unit), and a COVID-19 positive cohort in another area (the Queen Elizabeth Unit). This situation changed at the end of December when the caseload of COVID-19 positive patients dominated both clinical areas and may account for the low staffing productivity values in the first two months of data collection.

We also recognize that less experienced staff may take more time to evaluate, plan and complete interventions, and that our activity standards may have poorly estimated the actual time inexperienced staff spend delivering interventions. Other factors such as donning and doffing, providing clinical assistance outside predetermined therapy tasks and orienting to a constantly adapting working process were also likely to have influenced the 0.2WTE non-clinical allocation we applied. As staff training, supervision and delegation reduced in the later months of the analysis, productivity scores improved to 86% and 130% respectively, despite escalating patient numbers. These productivity scores suggest that the available clinical working time was appropriate for the number of interventions required, or the non-clinical time allocation was reduced as work processes became more efficient.

The advantages of evaluating productivity in relation to therapist to occupied bed ratio include an appreciation of the time commitment associated with non-clinical tasks (which grows as clinical banding increases), and recognition of the impact of sickness and annual leave on caseload performance. For example, the productivity associated with Dec 2020 was low, but accurately reflected the number of staff who required sickness absence due to government imposed COVID-19 isolation rules, and authorized absence over the Christmas period. However, productivity as a derived metric does not recognize patient complexity and represents patients as numbers, negating human factors such as communication, therapeutic relationship and rapport. It is difficult to establish the relationship between productivity and quality patient care when patient reported qualitative feedback was not investigated.

In addition, productivity metrics do not reflect whether the Physiotherapy needs of our critical care patients were being met. Evaluating the need for Physiotherapy intervention in critical care (and its objective assessment) remains an area of contention which is difficult to quantify outside individual therapist clinical reasoning [9], although evidence-based Physiotherapy recommendations for adult patients with critical illness do exist [19]. Critical Care Therapy services are historically delivered using a prioritization model necessitated by workforce capacity, where daily patient needs may not be met due to insufficient staffing, or excessive workload. We suggest that recording accurate staffing ratios and deriving productivity scores to align with the incidence frequency and timing of physiotherapy may be a starting point to explore this issue.

Our description of critical care Physiotherapy intervention during the second pandemic wave demonstrates a clear focus of interventions for respiratory optimisation and secretion management. There does not appear to be an association between volume of interventions delivered or staff productivity and duration to achieve functional milestones. During the final month of the analysis staff productivity was high, and rehabilitation tasks continued to be delivered, yet the time to achieve activity metrics was prolonged in comparison to preceding months.

This was a single centre observation and may not be representative of the experience of other sites. Our data is inclusive of all patients who occupied a critical care bed during the study period. Consequently, care must be taken when comparing this data to other reports detailing the experiences of invasively ventilated patients or critical care survivors. Although our aim was to provide a descriptive analysis of our observations, lack of statistical testing of observed associations explains our low confidence in definitive interpretation of the data.

We have presented a description of the Critical Care Physiotherapy service delivered to patients with confirmed COVID-19 over a four-month period coinciding with the second pandemic wave at one London Hospital. We have described Physiotherapy availability each month, in terms of therapist to occupied critical care bed ratios and provided a methodology for reporting productivity in relation to the time required to deliver both the volume and nature of interventions. Despite staff productivity improving over the four-month period our time to achieve mobility milestones were progressively longer than previously reported for non-COVID-19 populations. Competing clinical demands dictated by prioritization of respiratory management clearly influenced these observations, particularly since many respiratory and rehabilitation tasks require more than one therapist to safely perform. It remains unclear whether further enhancement of the therapist to occupied bed ratio would have improved the percentage of rehabilitation activity observed. Further investigation of the barriers to rehabilitation participation may assist in defining ideal Physiotherapy staffing requirements in critical care settings.

To read more about this article...Open access Journal of Anaesthesia & Surgery

Please follow the URL to access more information about this article

https://irispublishers.com/asoaj/fulltext/a-retrospective-observation-of-physiotherapy.ID.000570.php

To know more about our Journals...Iris Publishers

To know about Open Access Publishers