Authored by Noor Sameh Darwich*,

Introduction

Diaphragmatic dysfunction due to phrenic nerve involvement in patients with hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy (HMSN) (formerly known as Charcot-Marie-Tooth [CMT]) is uncommon in the early stages of the disease [1]. However, respiratory compromise due to diaphragmatic dysfunction caused by phrenic nerve involvement can be silent and insidious with minimal symptoms such as orthopnea [2]. In advanced HMSN disease with diaphragmatic paralysis, patients can present with hypercapnic respiratory failure requiring ventilatory support [3]. The prevalence of obstructive and central sleep apnea is higher in patients with HMSN [4]. Mild elevation in serum levels of creatine kinase (CK) may be due to denervated muscle with increase permeability of muscle membranes to enzymes such as CK. Recurrent episodes of significant increases in serum CK level more than five times the upper limit of normal in patients with HMSN suggest rhabdomyolysis [5]. This condition could be triggered by prolonged immobilization from advanced physical disability, overuse of proximal hypertrophic extremity muscles, or a concomitant underlying genetic mutation associated with rhabdomyolysis [6].

Case Report

A 39-year-old caucasian woman with a history of HMSN presented with shortness of breath, right upper quadrant abdominal pain, and back pain associated with having tea-colored urine along with generalized muscle aches. She had been diagnosed with HMSN at age 8 without genetic testing. Her brother had HMSN as well. Her past medical history was notable for periodic episodes of weakness associated with rhabdomyolysis, obstructive sleep apnea (using a continuous positive airway pressure device at night), hypertension, and occasional dysphagia to solid food for several years. The patient’s respiratory complaints started five years prior when she presented with respiratory distress and elevated serum CK, transaminases, and dark urine consistent with rhabdomyolysis. She developed acute kidney injury managed with intravenous hydration and noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (bilevel positive airway pressure) was used during her hospitalization. The patient had similar previous presentations at least twice in the last few years before the current presentation that required hospitalization for respiratory failure and rhabdomyolysis. She had baseline twopillow orthopnea, which increased recently to four pillows. The patient attributed her current condition to overexerting herself in the previous few days at work as she works at a library and walks with bilateral ankle-foot orthotics without an assistive device. She was taking acetaminophen for pain as needed.

Her previous spirometry in upright position five years prior showed severe restrictive dysfunction with forced vital capacity (FVC) 1.45 L (38% predicted), forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), 1.22 L (38% predicted), and FEV1/FVC (84% predicted) consistent with a restrictive pattern. The patient was unable to perform spirometry in the supine position due to respiratory distress. Before the current presentation, she required moderate assistance for grooming and total assistance for lowerbody dressing and bed/chair/wheelchair transfer, and maximum assistance for rolling and supine-to-sitting positioning.

On admission to the hospital, her blood pressure was 142/96 mmHg, temperature 97.1 F (36.2 C), pulse 114 per minute, respirations 24 per minute, and oxygen saturation 100% on 2 L/min oxygen per nasal cannula. Her physical examination was notable for claw-hand appearance of all fingers in both hands with fingers held in the flexed position but could be passively extended almost to the neutral position. Her motor examination revealed normal tone in bilateral upper and lower extremities. Deep tendon reflexes were 1/4 in bilateral upper and lower extremities with no ankle clonus and absent Babinski reflex with intact light touch sensation while her sensory examination during a prior admission had shown impaired temperature and vibration sensation in bilateral upper and lower extremities. At current presentation, she could not sit up on her own without rolling over to one side and had difficulty getting into bed with intermittent numbness of her fingertips and intermittent burning of the top of her thighs lasting for 15–30 minutes that resolved spontaneously. Her chest examination was notable for bilateral diminished breath sounds at the bases.

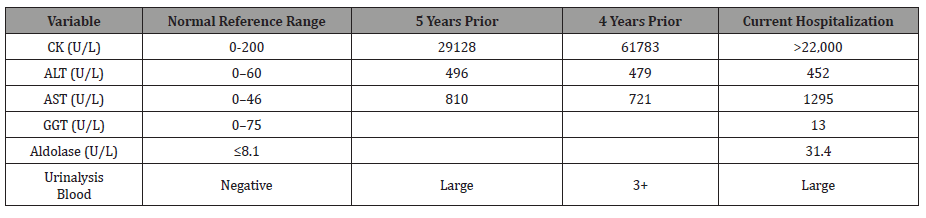

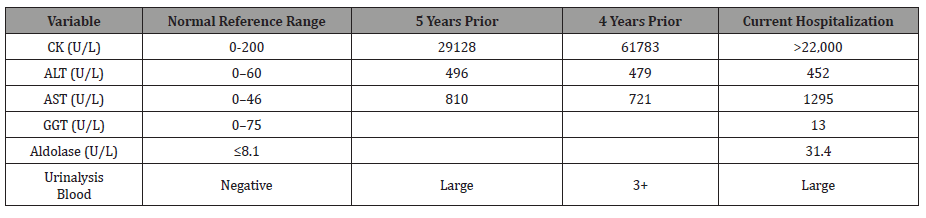

Laboratory test results from the current and previous hospitalizations are displayed in Table 1. Hepatitis serology was negative with normal serum acetaminophen level and negative COVID-19 PCR nasal swab.

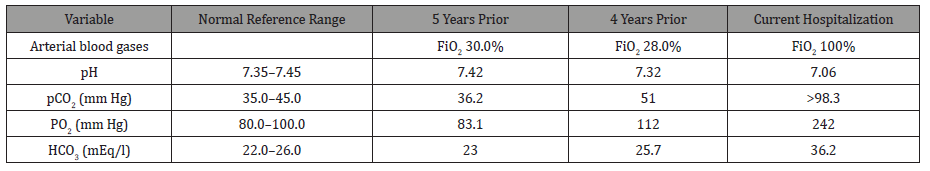

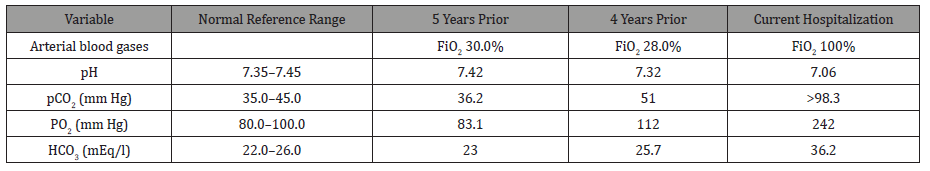

Ultrasound of the abdomen was unremarkable, and a chest X-ray revealed low lung volumes with elevated bilateral diaphragms. Computed tomography angiography of the chest revealed no signs of pulmonary embolism but was notable for bilateral lower lobes atelectasis. The patient was diagnosed with rhabdomyolysis and started on intravenous fluid therapy. On day 4 of hospitalization, the patient became increasingly lethargic, confused with questionable seizure-like activity in the extremities and acute respiratory distress. Arterial blood gases with comparisons to previous hospitalizations are displayed in Table 2.

Table 1:Laboratory test results from the current and previous hospitalizations.

Table 2:Arterial blood gases from current and previous hospitalizations.

The patient required intubation and mechanical ventilation and was transferred to the intensive care unit. An electroencephalogram revealed moderate nonspecific cerebral dysfunction of the left frontotemporal and right mesial frontal regions with severe nonspecific encephalopathy but no seizure or epileptiform discharges. Computed tomography of the head was unremarkable, and echocardiography revealed normal systolic function with ejection fraction 63%, grade 2 diastolic dysfunction with normal valve structure, and normal right atrial and ventricular function. She was weaned off the ventilator and was successfully extubated to noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV) with a face mask. Her serum CK levels trended down during hospitalization. The patient had a history of occasional swallowing dysfunction with a solid diet and reported an event in which she nearly choked on solid food at a restaurant and had to undergo the Heimlich maneuver. Videofluoroscopy revealed laryngeal penetration with thin liquids without evidence of tracheal aspiration and moderate residue within the vallecula and piriform sinuses. The patient was started on a full liquid diet with aspiration precautions.

She was discharged home with oxygen at 4 L/min during the day and NIPPV with average volume-assured pressure support (AVAPS) mode during sleep and the day as needed. The patient refused inpatient rehabilitation or any more testing, including rhabdomyolysis genetic testing, phrenic nerve electrophysiologic studies, ultrasound of the diaphragm, and the sniff test. She was referred to a genetics clinic for counseling. We believe that our patient with HMSN had developed hypercapnic respiratory failure due to diaphragmatic dysfunction caused by underlying phrenic nerve involvement. Her recurrent rhabdomyolysis was most likely due to prolonged immobilization from advanced physical disability combined with overuse of her denervated distal muscles and proximal hypertrophic muscles in the lower extremities. We cannot rule out an underlying coexisting genetic metabolic disorder causing episodic rhabdomyolysis.

Discussion

HMSN is the most common inherited disease affecting the peripheral nerves. It is characterized by a heterogeneous inheritance pattern and characteristic pathological, electrophysiological testing, clinical, and presenting features [7]. HMSN has a global prevalence and affects all races and ethnic groups. The prevalence of HMSN is 10–40 per 100,000, depending on geographic region. Although there is no ethnic predisposition, some rare HMSN subtypes are restricted to certain racial groups. HMSN may be less common among African Americans in the US [8,9]. The prevalence of HMSN might be underestimated because some patients are asymptomatic, and some mild cases go undiagnosed or are misdiagnosed [10].

HMSN can be inherited with an autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, or X-linked pattern. However, new spontaneous mutations (de novo) have been reported [11,12]. At least 80 gene mutations have been identified that encode proteins involved in myelin production, function, integrity, and maintenance. Other genes mediate functions in Schwann cells, axons, and other components of peripheral nerves. Some mutations affect genes responsible for mitochondrial proteins, while some are associated with unknown gene mutations [13]. Mutation types associated with HMSN can be whole-gene duplications, deletions, or point mutations. The majority of cases are related to mutations in four genes, PMP22, MPZ, GJB1, and MFN2. Duplications of the PMP22 gene account for 70–80% of cases [14]. HMSN is classified as types 1 through 7 with many subtypes within each type. Types one and two are the most common types. CMT1A accounts for 55% of all cases and 66.8% of CMT1 cases [15], while CMT2A accounts for most CMT2 [16]. The underlying pathology in peripheral nerves involves demyelination, axonal degeneration, or both [17].

Age of onset of symptoms varies by subtype, usually in the first decade for CMT1 and in the second or third decades for CMT2. Early-onset CMT2 can occur. A late-onset form of CMT2 presents between 35 and 85 years of age, while X-linked HMSN can be present early in infancy [18]. Disease severity is highly variable, and some individuals may show only minimal signs of weakness while others are disabled. The most common initial presentation of HMSN is distal weakness and muscle atrophy of the lower and upper extremities manifesting as difficulty walking, with frequent falls, poor finger control, and difficulty in hand manipulation and writing. There are also gait problems such as high-stepped gait, toe and flat foot walking, difficulty running and keeping up with peers [19], and frequently sprained ankles. Distal muscle atrophy causes stork-leg deformities with foot drop and deformities such as pes cavus (high arched feet) or pes planus (flat foot). These findings may be associated with impaired sensation presenting later, and they tend to be less prominent. They include a gradual decrease of proprioceptive, touch, vibratory sensation, and temperature sensation in the foot and hand. These symptoms predispose the patients to skin breakdown, non-healing foot ulcers, bony deformities of the foot due to loss of protective sensation. In all four limbs, pain sensation usually remains intact, accompanied by diminished or absent deep tendon reflexes [20]. Muscle cramps, numbness, and burning sensation with pain in extremities develop later [21]. Postural tremors and gait ataxia have been described in infantile-onset HMSN. Later in the course, foot deformities such as hammer toes, claw hand, hand weakness, and atrophy of the intrinsic hand and foot muscles can develop. Proximal muscles are less affected, and hypertrophy can develop as a compensatory mechanism in the early stage. However, proximal muscle weakness can develop late in the course of advanced disease. Intellectual disability with mental retardation has been reported in CMTX2 and CMTX4 subtypes with infantile onset.

HMSN usually affects long peripheral nerves. However, cranial nerve involvement such as optic neuropathy, sensory neuronal hearing loss [22], and dysphagia have been reported in CMT4B1, CMTX4, and CMTX5. There is sometimes slow conduction of electrical and magnetic stimuli in the facial, accessory, and hypoglossal nerves without clinical impairment of the cranial nerves [23]. Patients with CMTX1 can experience episodic acute or subacute onset of central nervous system manifestations characterized by transient neurological deficits associated with white matter abnormalities on brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). These deficits include transient ischemic attack, hemiparesis, quadriparesis, dysarthria, leukoencephalopathy, and ataxia, which resolve spontaneously without permanent deficit.

Nevertheless, brain MRI changes may persist for several years after the event [24]. Oculomotor nerve involvement presenting with diplopia is rare. Vocal cord paralysis, which can be unilateral or bilateral and unrelated to the degree of muscular weakness in patients with HMSN [25], is due to recurrent laryngeal nerve involvement; this has been reported in CMT2C, CMT4A, and CMT6 [26], and presents as dysphonia or stridor [27], increasing the risk of aspiration. These findings can be the presenting complaint of HMSN, often diagnosed with laryngeal electromyographic studies consistent with peripheral neuropathy affecting the vagus nerve and its laryngeal branch [28,29]. Autonomic nervous system involvement in HMSN can manifest as autonomic disturbances such as bladder dysfunction and orthostatic hypotension [30,31].

Although respiratory muscle and diaphragmatic weakness are uncommon in early disease of HMSN [32], the phrenic nerve may be involved. Phrenic nerve involvement manifests as diaphragm dysfunction or paralysis presenting with orthopnea and hypoventilation with hypercapnia that worsens during sleep, causing headache, fatigue, difficulty concentrating, and daytime somnolence. These findings may be relatively common in advanced CMT1 and CMT2 subtypes, including CMT2C, CMT1A, CMT4A, and CMT4B1 [33,34]. Observational studies attributed diaphragmatic dysfunction in a patient with HMSN due to coexisting diabetes mellitus. However, phrenic nerve neuropathy with diaphragmatic dysfunction was later described in a patient with HMSN without diabetes mellitus [35]. Respiratory compromise due to diaphragmatic paralysis can be silent and insidious and should be suspected in patients with HMSN presenting with minimal symptoms of orthopnea. The diagnosis should be considered before impending respiratory failure occur [36].

Phrenic nerve electrophysiological study in patients with CMT1 shows slow conduction velocity in most patients, and 24–30% have abnormal spirometry findings with reduced FVC. Even fewer patients (8%) reported having respiratory symptoms [37]. The leading underlying cause of respiratory failure in patients with HMSN is the denervation of the diaphragm and intercostal muscles [38]. However, thoracic cage abnormalities and neuropathic spinal arthropathy [39] with associated deformities such as scoliosis and kyphoscoliosis (reported in 42% of children with HMSN) can contribute to the restrictive ventilatory defect.

Demyelination abnormalities of the phrenic nerve were observed in patients with HMSN with the axonal form [40]. Patients with HMSN and diaphragmatic dysfunction and chronic hypoventilation are at high risk for developing central sleep apnea with desaturation and hypercapnia, mostly during rapid eye movement sleep. The latter occurs due to deficits in the functional utility of the diaphragm in respiration during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, while the activity of the intercostal muscles is markedly inhibited during this sleep stage [41]. Due to pharyngeal nerve neuropathy causing upper airway collapse, obstructive sleep apnea was also described in patients with HMSN with or without diaphragmatic dysfunction. There is an increased prevalence of obstructive and central sleep apnea in patients with HMSN. The severity of sleep apnea and underlying peripheral neuropathy in patients with HMSN are highly correlated. Restless leg syndrome and periodic leg movement disorder are found in many patients with CMT2 [42]. Diagnosis of HMSN depends on history, including detailed family history. Physical examination findings include distal muscle weakness/wasting accompanied by diminished deep tendon reflexes in upper and lower extremities with possible palpable enlargement of the peripheral nerve, which may occur secondary to nerve hypertrophy. There is also possible skeletal deformity, usually occurring at later stages of the disease. These findings are supported by electrophysiological studies, including nerve motor and sensory conduction velocity study (NCVS) and needle electromyography (EMG), followed by genetic testing to confirm the diagnosis [43]. Electrophysiological signs of demyelination can usually be found in all peripheral nerves, including those clinically unaffected. In the demyelinating form of HMSN (CMT1), NCVS findings vary depending on the phenotype. There is usually significant slowing of conduction velocity in both the motor and sensory nerves, mostly the motor nerves with values < 38–40 m/s (normal range > 50 m/s). In the axonal-loss type (CMT2), the conduction velocity is normal or slightly reduced with markedly low compound muscle action potential amplitude (CMAP). Sensory nerve action potential (SNAP) amplitudes are usually reduced. NCVS may be reduced even in asymptomatic patients with HMSN. Classic findings on needle EMG indicate muscle denervation with the presence of fibrillation potentials. In general, there is no correlation between the severity of muscle weakness and motor impairment. The degree of slowing on nerve conduction studies can be detected even in asymptomatic individuals as early as one year of age. However, in some phenotypes like the CMTX, NCV slowing is proportionate to clinical severity [44].

Nerve biopsy was a critical diagnostic tool for diagnosing HMSN in the past. Currently, it is not routinely performed unless the clinical presentation is atypical when genetic testing does not reveal a molecular diagnosis and when NCVS and EMG are not diagnostic [45]. Classical findings of nerve biopsy in patients with HMSN show onion bulb appearance, which is a characteristic feature reflecting repetitive demyelination and remyelination in CMT1. In CMT2, sural nerve biopsy shows axonal degeneration and nerve fiber loss [46]. Muscle changes seen in HMSN are due to denervation and reinnervation with secondary myopathic changes, neurogenic atrophy, fatty infiltration, and edema but no inflammatory infiltrate. Muscle MRI reveals high signal intensity within skeletal muscles on T2-weighted images [47].

Diagnosis of diaphragmatic dysfunction due to phrenic nerve involvement in patients with HMSN is challenging [48]. Suggested studies include chest radiograph, spirometry, diaphragmatic ultrasound, chest fluoroscopy with the sniff test, and phrenic nerve electrophysiological studies such as cortical and posterior cervical magnetic stimulation [49]. Chest radiograph findings are neither specific nor sensitive but can show low lung volumes with the elevation of diaphragms. Vital capacity is a sensitive tool and reliable measure of respiratory function compared to supine and erect positions. FVC may fall >25% from upright to supine, suggesting a significant compromise of diaphragmatic function in patients with neuromuscular diseases [50].

Other findings on pulmonary function testing in patients with HMSN include reduced maximal inspiratory pressure (MIP). This parameter reflects diaphragmatic strength. In HMSN, maximal inspiratory pressure is usually lower than -60 cm H2O, and maximal expiratory pressure (MEP) can be mildly reduced. It should be noted that these tests are effort-dependent [51]. Fluoroscopy with sniff test involves quickly breathing in through the nose. It is a straightforward assessment of diaphragmatic motor function that confirms the absence of muscular contraction of the diaphragm during inspiration, where the diaphragm moves downwards as in healthy patients. There is a 1–2.5 cm excursion during normal quiet breathing, and in deep breathing, the excursion may be 3.6– 9.2 cm. In patients with diaphragmatic dysfunction, the affected hemidiaphragm does not move downwards during inspiration, or paradoxical motion can occur. Sniff fluoroscopy is helpful in the diagnosis of unilateral diaphragmatic paralysis. However, in bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis, the test can give the false appearance of caudad displacement of the diaphragm due to accessory muscle contracture in bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis [52]. Ultrasonography of the diaphragm with static measurement of the diaphragm thickness and changes in thickness during inspiration has been used to confirm diaphragmatic paralysis. However, the test is operator-dependent and has not been adopted for standard evaluation of diaphragm paralysis. Phrenic nerve enlargement sometimes is revealed on ultrasound in patients with HMSN [53].

Several electrophysiological studies are used to diagnose diaphragmatic paralysis in neuromuscular diseases with phrenic nerve neuropathy. Nevertheless, these diagnoses can be challenging, and expertise in interpretation is required [54]. Phrenic nerve stimulation testing accompanied by measurement of diaphragm CMAP using transcutaneous electrical stimulation or cervical magnetic stimulation of the phrenic nerve in the neck while recording diaphragm CMAP at the chest wall surface by two electrodes is usually an easy test with reliable results [55]. Another test is transdiaphragmatic pressure (Pdi), representing the difference between gastric pressure and pleural pressure. Pdi can be monitored using two trans-nasal thin-walled catheters. One is placed in the lower third of the esophagus above the diaphragm to assess changes in pleural pressure, and the second is placed in the stomach to measure abdominal or gastric pressure. Pdi can be measured during peak tidal volume inspiration and after phrenic nerve stimulation. At peak tidal volume inspiration, the value for Pdi is positive if the diaphragm is working normally and negative in diaphragmatic paralysis [56]. Diaphragmatic electromyography can also help differentiate between diaphragmatic paralysis due to underlying neuropathy and paralysis caused by myopathy. Nevertheless, it carries some risk from needle placement in the diaphragm. Dynamic MRI of the diaphragm is a promising noninvasive new technique for evaluating diaphragm excursion, motion, and volume [57].

Laboratory findings in HMSN may include elevated serum CK levels. As many as 50–75% of patients with motor neuron disorders such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [58], spinalbulbar muscle atrophy (SBMA), and HMSN have elevated serum CK levels. These elevations are usually up to five times the upper limit of normal at rest. These values can be up to ten times the upper limit of the normal value after activity. These changes correspond to the degree of muscle denervation and compensatory reinnervation with muscle fiber hypertrophy and the degree of myopathic changes seen on muscle biopsy [59]. The significant elevation of CK in HMSN can be recurrent and episodic with flare-ups due to exacerbating factors such as period of prolonged immobility (which leads to rhabdomyolysis), emotional stress, alcohol use, pregnancy [60], and drugs such as vincristine, dapsone, metronidazole, and nitrofurantoin [61]. Vincristine, a chemotherapeutic agent used to treat various malignancies in both children and adults, can exacerbate and cause rapid deterioration of HMSN or reveal a previously undiagnosed case of HMSN [62]. In ALS, up to 40–75% of patients had elevated serum CK levels, while 80% of patients with SBMA has elevated serum CK levels. These elevations may be seen many years before the onset of clinical symptoms, while muscle biopsy shows changes of denervation atrophy without myopathic changes [63]. The precise underlying mechanisms of elevated CK levels in HMSN are not yet clear. However, one study suggested possible leakage of CK across cell membranes in denervated muscle tissue secondary to increased myocyte permeability or disturbed metabolism due to denervation and reinnervation processes. The latter lead to increased endogenous triphosphatase activity in the mitochondria of denervated muscle, leading to increased CK levels in patients with HMSN [64]. Finally, increased CK levels may result from the overuse of denervated muscle, increasing permeability, and compensated hypertrophic proximal muscle during ambulation in disabled patients with HMSN. The period of prolonged immobility may also contribute to the increased CK levels [65].

Correlations between elevated CK levels with the extent of muscle mass undergoing denervation and atrophy have been described. Prominent elevation of serum CK was more frequent among patients with the axonal phenotype of the MPZ mutation in HMSN [66]. In animal studies, muscles undergoing neurogenic atrophy were more permeable to CK than normal muscle. Between 3% and 30% of a subset of HMSN patients in a Japanese study were reported to have increased CK levels. Other muscle enzymes that may be elevated in HMSN are AST, ALT, lactate dehydrogenase, and aldolase [67]. Associated genetic mutations for rhabdomyolysis have been found in rare subtypes of HMSN. Recurrent episodes of rhabdomyolysis caused by LPlN1 gene mutations were described in a patient with CMT1A [68]. The C59T mutation in exon 1 of the MPZ gene has been associated with late-onset axonal type HMSN with elevated serum CK levels. Mitochondrial dysfunctions such as mitochondrial trifunctional protein (MTP) deficiency, a rare mutation autosomal recessive disorder of mitochondrial fatty acid in HADHB (hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase β-subunit) gene can cause recurrent rhabdomyolysis, and the presentation can mimic peripheral neuropathies such as HMSN [69,70,71]. Management of patients with HMSN includes genetic counseling and multispecialty supportive care to relieve symptoms, improve mobility, and improve flexibility and muscle strength to increase independence. There is currently no effective medical treatment to prevent or retard any of the pathophysiologies of HMSN, including abnormal myelin, myelin degeneration, and axonal degeneration [72,73].

Rehabilitation of HMSN patients relies on physical and occupational therapy to improve the symptoms and reduce or delay the risk of muscle contractures. These therapies involve moderate low-impact activities, including low-intensity exercises such as stretching, swimming, and weight training. These were found to be more beneficial than high-intensity exercise [74]. Orthoses to stabilize ankles, walking aids, fall precautions, ankle/leg braces, and podiatry consultations for appropriate footwear are needed occasionally. Various orthopedic procedures may be necessary to correct severe spinal or foot and joint deformities. These include osteotomy, arthrodesis, spinal surgery, and plantar fascia release, with pain management for musculoskeletal and neuropathic pain. Special care must be taken to avoid neurotoxic drugs such as neuromuscular blocking agents for patients undergoing anesthesia, and there must close monitoring postoperatively [75,76,77]. NIPPV is effective respiratory support when hypoventilation with hypercapnia and respiratory impairment occur in patients with HMSN. Long-term NIPPV is well tolerated in patients with neuromuscular disorders [78]. NIPPV can help manage muscle weakness with diaphragm dysfunction and sleep apnea [79]. NIPPV at night improved survival in patients with neuromuscular disease and respiratory failure. It also improved their quality of life. Continuous positive airway pressure therapy is not usually recommended in patients with neuromuscular disease, and bilevel positive airway pressure therapy is more effective than CPAP in these patients [80,81]. Diaphragm pacing has shown equivocal results in neuromuscular disease patients and has never been explicitly tested in HMSN patients.

Several potential experimental therapies for HMSN are being evaluated in clinical trials. These include the use of progesterone antagonists in animal models. These agents may slow disease progression [82]. High-dose ascorbic acid (vitamin C) [83] promotes myelination. However, it failed to show any significant benefit [84]. An ongoing trial of polytherapy (PXT3003) is studying the combination of baclofen, naltrexone, and sorbitol [85]. This combination was proposed to downregulate PMP22 overexpression. It may also improve myelination and axonal regeneration in patients with CMT1A, the most common form [86].

Stem cell and gene therapies are promising treatment options under investigation for patients with HMSN, including gene replacement, gene addition, suppression of mutant gene expression, or modulation of gene expression by using a highly modified virus as a vector to carry and insert a functional version of the gene to replace a defect gene into the cells such as Adenoassociated virus gene therapy technique. Implanting tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cells (T-MSCs) after maturation into Schwann cells called T-MSC-SCs, then transplanting these cells into the muscles is another potential treatment for HMSN [87,88]. Although patients with HMSN should have a normal life expectancy, those with advanced disease complicated by respiratory failure have significantly shorter life expectancy than the normal population. Death in infancy in some subtypes of HMSN has been reported. Disabilities are common.

Conclusion

It is essential to have a high clinical suspicion of diaphragmatic dysfunction due to phrenic nerve involvement in patients with advanced HMSN disease. This complication should be recognized early in patients with orthopnea, daytime somnolence, and hypercapnia [89]. Closely monitoring of respiratory function status and sleep-disordered breathing is recommended in patients with HMSN [90]. Spirometry while supine and upright, phrenic nerve electrophysiological studies, the sniff test, and ultrasound of the diaphragm can be valuable diagnostic tools to aid in diagnosing diaphragmatic paralysis [91,92]. NIPPV has been used with success in patients with respiratory failure due to neuromuscular disorders in general and in HMSN disease in particular. It has been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality and improve quality of life [93,94]. While mild elevations in serum CK levels are expected in patients with HMSN, significant elevations should alert physicians to investigate underlying causes of rhabdomyolysis such as coexisting genetic metabolic disorders, medications or drugs, prolonged immobilization, overexertion, or infection [95].

To read more about this article....Open access Journal of Neurology & Neuroscience

Please follow the URL to access more information about this article

https://irispublishers.com/ann/fulltext/hereditary-motor-and-sensory-neuropathy-with-hypercapnic-respiratory-failure.ID.000733.php

To know more about our Journals...Iris Publishers

To know about Open Access Publishers