Authored by Dereje Mosissa

Abstract

This study is an investigation of effectiveness of soil and water conservation practices as climate smart agriculture and its’ contribution to the livelihoods of smallholder’s farmers in Bambasi District of Northwestern Ethiopia. It was hypothesized that there is no relationship between factors contributing to the adoption of SWC technologies and a number of SWC technologies adopted, as well as there is no relationship between the number of SWC technologies used by farmers and access to the livelihood assets. In order to address the objectives, both primary and secondary data were used for the study. The study applied a non-experimental design (explanatory) to collect primary data from a sample of 270 households drawn from the three Kebeles. Stratified random sampling technique was also used along with the simple random sampling technique in each stratum. The data collected was then analyzed by inferential statistics such as chi-square by using STATA 14.2 and Microsoft office Excel. Perceptions The study found out that most adopted SWC technologies are crop rotation, level bund, agricultural inputs and Fanya Juu terraces, of which few of them were considered as effective while the main factors influencing their adoption are farm size, having livestock, crop yield, farmers’ perception of the soil erosion problem, access to extension services and experience, availability of inputs support and steep slope. It was found that 9.3% of respondents adopt at least one technique while 37.8% use the four identified SWC technologies. The results revealed that respondents have access to livelihood assets (natural, human, social, physical and financial assets) found in the area of study. The statistical test showed that farm size, crop yield, perception of soil erosion, availability of inputs supports, the availability of training and access on it as well as farmers’ experience, Natural and social assets and steep slope have a connection with adoption of SWC technologies, while the others not. The study concluded that most of the participants were willing to maintain soil as a valuable resource and apply SWC technologies for maximizing their benefits but expressed the need for the continuing support of the implementation. Further, it also brings to a close that conservation efforts ought to focus on areas where expected benefits are higher, especially on the steeper slopes, in order to encourage the use of the SWC technologies.Keywords: Adaptation; Livelihood assets; Agricultural technology; Small holders; Soil erosion

Backgrounds of the Study

Globally, large areas of land are being affected by land degradation, partly resulting from unsustainable land use. This is particularly the case in developing countries, which are especially vulnerable to overexploitation, inappropriate land use, and climate change. Bad land management, including overgrazing and inappropriate irrigation and deforestation practices often undermines productivity of land [1]. In the context of productivity, land degradation results from a mismatch between land quality and land use [2]. Land degradation as a result is a biophysical process driven by socioeconomic and political causes [3].Land degradation is related to climate and soil characteristics, but mainly to deforestation and inappropriate use and management of the natural resources, soil and water. It leads both to a nonsustainable agricultural production and to increased risks of catastrophic flooding, sedimentation, landslides, etc., and the effects of global climatic changes [4].

The problems of soil and water degradation and derivative effects are increasing throughout the world, partially due to a lack of appropriate identification and evaluation of the degradation processes and of the relations causes-effects of soil degradation for each specific situation, and the generalized use of empirical approaches to select and apply soil and water conservation practices [5].

In addition to the negative effects on plant growth and on productivity and crop production risks, soil and land degradation processes may contribute, directly or indirectly to the degradation of hydrological catchments, affecting negatively the quantity and quality of water for the population and for irrigation or other uses in the lower lands of the watershed [5]. The productivity of some lands has declined by 50% due to soil erosion and desertification. Yield reduction in Africa due to past soil erosion may range from 2 to 40%, with a mean loss of 8.2% for the continent. In South Asia, the annual loss in productivity is estimated at 36 million tons of cereal equivalent valued at US $5,400 million by water erosion, and US $1,800 million due to wind erosion. It is also estimated that the total annual cost of erosion from agriculture in the USA is about US $44 billion per year, that is about US $247 per ha of cropland and pasture.

On a global scale the annual loss of 75 billion tons of soil cost the world about US$ 400 billion per year, or approximately US $70 per person per year. Thus, land degradation will remain an important global issue of the 21st century because of its adverse impact on agronomic productivity, the environment and its effect on food security and the quality of life [3]. Soil loss was estimated by using the universal soil loss equation calibrated from field data collected on more than 19,000 fields. Seasonal soil losses ranged from 1 t/ha (0.4 ton/acre) to 143 t/ha (63.8tons/acre); the average seasonal soil loss was 5 t/ha (2.2 tons/acre). Soil loss in Ethiopia showed a pattern of regional differences that closely followed variations in rainfall and topography. The development of regional strategies to minimize agricultural erosion is likely to be more effective than a single national policy [6].

The study carried out in different areas in Ethiopia showed that the effects of soil degradation and water shortages on crop productivity have induced researchers to introduce some innovative practices such as mulching, bunding, contour ridging, ripping, minimum tillage and others check the down wardspiral in agricultural production. Varied soil and water conservation practices requiring varied farmer inputs have been promoted among farmers for over a decade now [7,8].

Materials and Methods

Materials used

The study was conducted in Benishangul Gumuz regional state, in Bambasi Woreda, which is one of the twenty Woredas of the region. Bambasi Woreda is found 45km far from Asossa town which is the capital city of the region. It is located in the northern part of the region between09° 47’ North latitude and 34°47’ East longitude (Figure 1).The Woreda is bordered by Oromia regional state and Maokomo special Woreda in the south and south west and, Asossa Woreda in the west and Oda Buldegelu Woreda in the north east.Administratively, the Woreda is divided into 38 kebeles. 19 kebeles are inhabited by indigenous people, 17 kebeles are settled areas created during the Dreg regime and 2 kebeles are under the municipality of Bambasi town. And also new refugee camp is found in the Woreda. Based on the document analysis of the Bureau of Agriculture, Woreda Agricultural and rural development office and Woreda rural land administration and use office, there are several Kebeles which have encountered intense land cultivation in the Woreda. These includeSonka, Keshmando-qutir 5, Sisa qutir1, Bashimakergige, Womaba-Selema, Bambasi 02, Amba 16, Mutsa, Jematsa, Sonka and Mender 55 (Figure 1).

Based on CSA [9] data, the total population of the Bambasi Woreda is about 70,350 people. The peoples found in this Woreda are composed of a variety of ethnic groups including Berta, Amhara, Oromo, and Tigre. There are also refugees from South Sudan in the woreda. In 2014 the total number of households is 12,539 of which 11,912 were male headed and 627 were female headed. Their livelihood structure is mainly depending on agriculture and traditional gold mining.

The Woreda covers an area 472,817 hectares, of which 221,016 hectares are used for cultivation but now a day only 72,379 hectares are cultivated land, 10,000 hectares are pastureland, 63,756 hectares are non-cultivated land and 174,820 hectares are forest area, 1,200 hectares are mountain area, 1,797 hectares are irrigation area, 228 hectares are perennial crop area. The major food crops or cereals grown in the area are maize, sorghum and teff. Oil crops and other crops are also produced in the area. The average land holding is 4.65 hectares per household.

The main economic base of the woreda is farming, where major crops are maize and sorghum. There has been no crop rotation during the last several years. The average productivity of maize per hectare in Bembasi is stated to be 60 quintals with the application fertilizers and for sorghum it is about 25 quintals. These yield figures are considered good for these acidic acrisoils, with low fertility. Experts still believe the yields can be increased. Fishing and mining in Dabus River are further practiced by the Berta ethnic group both as a supplementary economic and as a food source. This river serves as a regional boundary between Oromiya and Benishangul- Gumuz. A Sustainable Land Management (SLM) project is on-going and soil and water conservation activities are widely undertaken with the support of different NGOs and the regional agricultural research center. Fertilizer application has been improving in the last couple of years and now the communities have recognized that it is impossible to produce without fertilizer. However, the use of fertilizers is still low compared to other developed regions of the country.

Bambasiworeda is found in the southern part of the Assosa City. Climate data from the nearest meteorological stations Amba 16 (only rainfall, from 2005-2018) was extracted and presented in Figure 2 and the woreda is located at 9o 57’ 12.4’’ N Latitude and 34 o 39ʹ 21.7ʹʹ E Longitude, with an altitude of 1554 m.a.s.l.

The average annual rainfall is 1381.42 mm, while the mean annual maximum temperature is 28.37 °C. The area is characterized by unimodal rainfall distribution with the rainy season extends from March to November and one distinct short dry season extending from December to February (Figure 2). Typically, during the onset of the main rainy season, the first two months receive small amount and gradually reach to its peak in August. More than 55% of the mean annual rainfall falls from June to August.

The mean maximum monthly temperature is about 28.37° C. Mean maximum monthly temperature reaches to its peak during March followed by April and February, with a temperature of 32.69° C, 32.05° C and 31.96° C, respectively; whereas, the lowest mean minimum monthly temperature occurs during December with a temperature of 13.28° C. This climate diagram of Bambasi Woreda shows water stress in January, February and November, and excess water in May, June, July August and September. The red line is temperature, measured on the left axis. The purple line is precipitation, measured on the right axis (Figure 2).

Research methodology

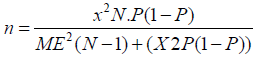

Descriptive statistics of farmers’ characteristics, socioeconomic and environmental characteristics, geographical characteristics, factors of adoption of SWC technologies and their benefit will be analyzed. These statistics included descriptive and chi square statistics. This was helped to outline the influence of farm characteristics and socioeconomic and environmental characteristics as well as their expected outcomes from adoption of SWC technologies in their farm’s location. The study targeted smallholder-farmers whose farms were located in areas prone to soil erosion and applied soil and water conservation technologies in their farms. The sample size of this study was calculated based on the following formula Krejcie & Morgan (1970): Where:

Where:n: required sample size

X: Z value (confidence level – standard value of 1.96)

N: total number of farmers living in the study area:

P: Standard deviation (standard value of 0.5)

ME: Margin error at 5% (standard value of 0.05)

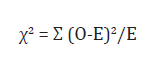

The method which is used during the research was a questionnaires, interview and observation methods was used. Descriptive statistics was used in the data analysis and Chi-square was also used in hypothesis testing. Application of the appropriate statistic helps a researcher to decide if the difference between the two groups‟ scores is big enough to represent a true rather than a chance difference. Choice of appropriate statistical techniques is determined to a great extent by the research design, hypothesis, and the kind of data that was collected. In fact, after data collection, the data was edited and coded and subsequently, the data was entered into SPSS. The major types of statistics are measures of central tendency, percentages, pie charts and bar graphs were used in the data analysis. Additionally, all hypotheses were tested by Chi square. The Chi-square (χ2) was computed using the following formula:

Where:

O – Observed frequency

E – Expected frequency

Ʃ (O-E)2 – Sum of the squares of the differences between Observed and Expected frequencies.

The χ2calculated was compared with χ2critical at a significance level of 0.05 and degrees of freedom which was determined as follows:

Degrees of freedom (df) = (r – 1) (c – 1)

Where r: number of rows

c: number of columns

Results and Discussion

Socio demographic characteristics of respondents

Response Rate: A total of 331 questionnaires were distributed out of which 270 questionnaires were returned. This was because some of the respondents were too busy that they were not able to attempt the whole question. This response was good enough and representative of the population and conforms to Mugenda O.M and Mugenda AG [10] stipulation that a response rate of 70% and above is excellent. All 270 samples of respondents were all farmers and relied on natural resources for their basic needs. The study results indicated more than three quarter of the respondents (87 %) are smallholder farmers with farm size below two hectares, while only quarter (13%) of the sampled respondents have farms with size of greater than or equal to two hectares.

Four age groups of respondents were identified: below or equal to 20, between 21 and 40, between 41 and 60 and then greater or equal to 61 years old. The findings indicate that most of the respondents (83.7%, n=226) are in the age vary from 21 to 60 years (Table 1). The average age is 44.17 years for all respondents, max=63 and min=18 years. Additionally, the average age for women is 42.5 years and 45.8 years for men.

To read more about this article.... Open access Journal of Agriculture and Soil Science

Please follow the URL to access more information about this article

https://irispublishers.com/wjass/fulltext/the-effectiveness-of-soil-and-water-conservation-as-climate-smart-agricultural-practice.ID.000542.php

To know more about our Journals....Iris Publishers

To know about Open Access Publishers

No comments:

Post a Comment