Authored by Jarbas Faraco Maldonado Loureiro*,

Abstract

Esophageal perforation is a serious condition that has an unfavorable prognosis, especially when diagnosed late. The main causes are iatrogenics and foreign body ingestion. Clinical manifestations may be nonspecific, which delays their identification. When suspected, exams such as radiography and tomography should be requested to confirm the perforation. The conventional treatment is surgical, in addition to antibiotics and suspension of oral diet. Endoscopy has become an option in the therapeutic arsenal, being less invasive and showing good results. However, as seen in this case report, when the patient does not have systemic manifestations, expectant (non-surgical) management may be an appropriate option with a satisfactory outcome.

Keywords: Perforation; Esophagus; Endoscopy; Foreign body; Clinical management

Introduction

Esophageal perforation is considered a serious and rare medical condition that is associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality [1]. It has nonspecific clinical manifestations, which contribute to late diagnosis, causing worse outcomes. The main causes are: iatrogenics (after endoscopic procedures), trauma, ingestion of a foreign body or chemical substance. The perforation can also be spontaneous, which is known as Boerhaave syndrome. Regarding the ingestion of foreign bodies, in adults it usually occurs incidentally and in most cases the foreign body spontaneously progresses through the digestive tract and does not require additional conduct. Among the objects accidentally ingested, the bones of animals are considered the most prevalent, they can be sharp, generating a greater risk of perforation [2].

The clinical presentation of perforation is usually nonspecific, with pain being the most common symptom. The manifestations will depend on where the esophagus was perforated (cervical, thoracic or abdominal). When the involvement is cervical, symptoms can be dysphagia and neck pain. Perforation of the thoracic esophagus may present with pain in the back, chest or epigastric region. Distal lesions may cause abdominal pain and peritonitis. Other less frequent symptoms are vomiting, nausea and subcutaneous emphysema. Signs such as fever, hypotension and tachycardia may appear, characterizing systemic involvement. Early diagnosis is a challenge due to the nonspecific presentation of the condition. Imaging tests such as contrast radiography and tomography can characterize the perforation. Digestive endoscopy can be requested to elucidate the symptoms, it is able to identify the perforation and may also be a therapeutic option [3].

The management of patients with perforation is critical, because they can rapidly progress to septic shock, so they should be closely monitored. The main goals of treatment are infection control, maintenance of nutritional status and evaluating the therapeutic possibilities for repairing the perforation. Treatment is divided into surgical and non-surgical approaches. Non-surgical management can be performed in the portion of patients who do not show signs of septic shock. The main conducts are the initiation of antibiotic therapy and suspension of the oral diet using an enteral or parenteral diet until the resolution of the esophageal perforation is assured [1].

Digestive endoscopy has become more relevant in the treatment of esophageal perforation in the last decade. It can be used by itself, especially when the perforation is identified early (<24 hours) or associated with surgical treatment [4]. In cases where there is contrast extravasation, empyema or mediastinal contamination, drainage is mandatory. Interventional endoscopy techniques such as the application of clips, endoscopic stents and vacuum therapy have become less invasive options compared to conventional surgery techniques, therefore providing lower treatment-related morbidity and mortality.

The application of clips by endoscopy can be a treatment option, but they are used in very specific cases of early perforation, minimal inflammation, small holes (< 5 mm) and in the absence of fistulas. There is the option of over-the-scope (OTS) clips which are used in larger perforations. Endoscopic stents can also be used to treat perforation, combined or not with percutaneous drainage therapy, but the biggest complication is their migration, which limits their use. Predictors of good response to treatment are early identification of perforation and smaller luminal aperture. Vacuum therapy is a new treatment option, which has proven to be effective and its clinical use has become increasingly frequent. It is based on the application of a drainage system with negative pressure in intraluminal or intracavitary topography guided by endoscopy. Vacuum therapy results in decreased edema, removal of infected secretions, and gradual closure of the lesion [1]. Surgical treatment options includes draining the contaminated space, primary perforation repair, esophageal bypass, and esophagectomy. Surgical management is indicated for extensive lesions and in cases where there are severe complications, such as mediastinitis1.

Case Presentation

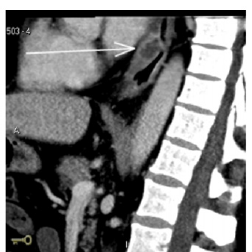

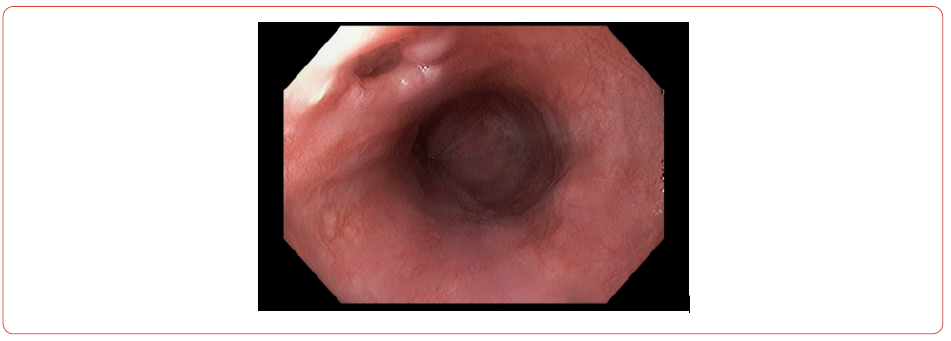

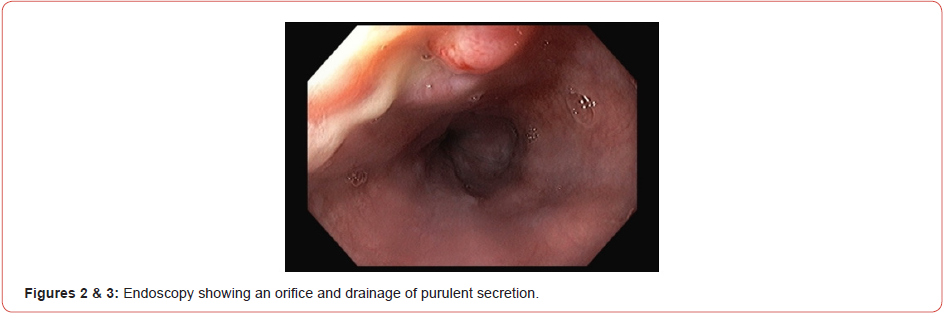

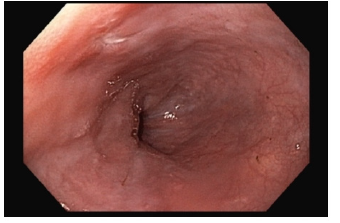

63-year-old male, with arterial hypertension and dyslipidemia, without other comorbidities. It started with pain in the lower thoracic region associated with a feeling of bloating. Symptoms started after participation in a family barbecue where fish and bone-in beef were served. The condition evolved for 5 days, when it became more intense and associated with difficulty of feeding, tolerating pasty foods. He sought medical care in the emergency, where he was evaluated and initially laboratory tests showed a significant increase in leukocytes and C-reactive protein. Abdominal ultrasound did not show relevant changes. It was decided to perform a tomography of the abdomen and chest, which showed thickening of the lower third of the esophagus, associated with parietal ulceration and reactive lymph node enlargement (Figure 1), and also upper digestive endoscopy which showed the presence of an 8 mm orifice in the distal esophagus draining purulent secretion (Figure 2 & 3). An evaluation was requested from the surgical team and as the patient remained in good general condition, with no signs of sepsis, a non-surgical approach was chosen. Antibiotic therapy was started with ceftriaxone and metronidazole, suspension of the diet oral and insertion of a nasoenteral tube to preserve the nutritional status. Patient evolved with progressive clinical and laboratory improvement. One week later, a new tomography was performed, which showed regression of the esophageal thickening and a new endoscopy (Figure 4) which showed complete closure of the orifice. The patient was discharged from hospital 10 days after admission, with good acceptance of the oral diet, without complaints and in excellent general condition.

Discussion

Esophageal perforation, when diagnosed late, that is 24 hours after the injury, has worse morbidity and mortality rates. The fact of having non-specific symptoms contributes to delay the diagnosis, which will be identified only when the patient shows signs of systemic involvement, which demands more aggressive therapeutic approaches. For this reason, a detailed clinical history should be taken to increase diagnostic suspicion and early institution of treatment. To confirm the diagnosis, it is necessary to perform additional exams, such as tomography. Endoscopy, in addition to being a diagnostic option, is also considered a therapeutic option.

After diagnosing the perforation, the fundamental therapeutic approaches are infection control, maintenance of nutritional status and repair of the digestive tract. However, in cases where the patient is in a good clinical condition, without signals of systemic involvement or the presence of collections, management with antibiotic therapy and enteral nutrition can present a good clinical response and favorable evolution, without the need for surgical or endoscopic intervention, as it was described in this case report. In the case discussed, the diagnosis was made late with the patient presenting an insidious evolution and seeking medical care five days after the symptoms. When the perforation was diagnosed, the presence of a foreign body was not identified however due to the clinical history, the hypothesis was accidental ingestion of a foreign body. As the patient had no systemic signs, with a small perforation and drainage into the esophageal lumen, clinical treatment was chosen and showed an adequate response.

Conclusion

Therefore esophageal perforation is a serious medical condition that requires intensive patient care due to the high rates of complications. Early diagnosis is a challenge, but it is of paramount importance for a better prognosis. Conventional treatment for perforation is surgical, but in cases where the perforation is small, tamponade and the patient is stable with no evidence of sepsis, clinical management can be successfully performed. Surgical treatment is recommended in cases of extensive esophageal lesions and when there are signs of systemic involvement.

To read more about this article...Open access Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology

Please follow the URL to access more information about this article

No comments:

Post a Comment